Learn about horrendous crimes and unscrupulous criminals, corrupt politicians and the lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous and treacherous are just a few...

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government fully controlled Australia’s telephone network and the communications carrier Telecom, which has since been privatized and rebranded as Telstra. During this period, Telecom maintained a monopoly over communication services, resulting in the gradual decline of the network's infrastructure into disrepair.

Four small business owners—the individuals known as the Casualties of Telstra (COT)—faced profound communication challenges that significantly disrupted their ability to operate effectively. These challenges arose from a lack of reliable telephone service, which hampered their daily business operations and led to frustrating losses. In response to their plight, the Australian government’s communications authority, AUSTEL (now known as ACMA), stepped in to offer them a commercial assessment process. This was initiated with the involvement of AUSTEL and the Minister for Communications.

In a remarkable and unprecedented move, the government promised the COT owners that if they abandoned their push for a comprehensive Senate Estimates Committee investigation into their claims, it would honour a previously signed agreement with Telstra and compel Telstra to supply the crucial documents the owners needed to substantiate their allegations. This agreement was historically significant, as no such arrangement had ever been brokered between a government and its citizens since the establishment of the Federation.

At the time, the prospect of a Senate investigation loomed ominously over the government. There was a palpable fear that such an inquiry might uncover a disturbing reality: Telstra and its employees were allegedly siphoning off millions of dollars from government funds while systemic billing problems festered unchecked. At the moment when Telstra’s Corporate Secretary, Jim Holms, signed the Fast Track Settlement Proposal on November 18, 1993, the full extent of these issues remained largely concealed. Still, signs of severe trouble were beginning to surface. The four COT Cases formally signed their agreements just a few days later, on November 23, 1993.

In addition to addressing the grievances of the COT owners, AUSTEL also facilitated an agreement on behalf of the government under the Commercial Arbitration Act for other Australian citizens who had reported similar telecommunications complaints. This process was modelled after a system successfully implemented with its then-British-owned telecom provider in the United Kingdom.

However, the four COT Cases were urgent. They faced a critical deadline: if they did not sign their special agreement by the close of business on November 23, 1993, they would be forced to navigate the traditional and often arduous arbitration process. The government made this special offer to recognize the tireless efforts of these four business owners, who had collaborated closely with AUSTEL and local government ministers to advocate for improved telephone services that would benefit all Australians (Refer to official Senate Hansard titled A Matter of Public Interest Senate Hansard Evidence File No-1)

Tragically, circumstances took a much darker turn when AUSTEL initiated a covert investigation into the distressing claims put forth by the business owners. The outcome, unveiled in AUSTEL's publicly available version of their COT Cases report, was sanitized to obscure the true extent of the issues endured over the seven long years that Telstra steadfastly denied any systemic problems existed. For a more precise understanding, the unsanitized version of the findings from their investigation into my claims can be found in points 1 to 212 AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

The government's deliberate concealment of critical adverse findings during the arbitration process I was compelled to navigate represented a significant breach of trust. The situation was further exacerbated by the actions of the appointed Assessor and the Administrator, who callously refused to honour my existing Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP). In this proposal, I submitted a complete and comprehensive log of my complaints related to the interim claim material, which was never assessed or returned to me. The four COT Cases were pressured to abandon our FTSP process and sign their arbitration agreement, leaving us to face the unforgiving legal landscape without support.

On 30 April 1995, during the arbitration process, the technical consultants for the arbitrators stated in their final evaluation that a comprehensive log of Mr. Smith's complaints did not seem to exist (see Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D). However, this log of my complaints was included in my original settlement proposal, which I was forced to abandon.

None of us had the financial means to challenge the powerful government telecommunications entity in court, so we reluctantly opted for arbitration—blind to the fact that Telstra’s lawyers had crafted the arbitration agreement (the rules) to favour their client heavily. This grim double-edged sword starkly illustrates individuals' struggles to seek justice and accountability amid overwhelming resistance. It is a powerful narrative of determination, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of fairness that resonates deeply with many who have faced similar challenges.

The COT cases are troubling in Australia's legal and political history. They are characterized by rampant government corruption, systematic bribery, and a persistent pattern of misleading and deceptive conduct that tainted the government-endorsed arbitrations meant to resolve these disputes. This examination reveals a complex and troubling landscape in which ethical standards have been compromised, leading to significant injustices.

A disturbing pattern of corruption within the Australian government is at the heart of this saga. Public servants entrusted with the responsibility to uphold justice and integrity have engaged in or turned a blind eye to egregious crimes and unethical conduct. This analysis aims to uncover the key figures involved—those unscrupulous politicians who have sacrificed public trust for personal gain, whose actions have encouraged a culture of impunity, and whose legacies continue to influence the political terrain. We will also examine their legal representatives, some of whom still actively practice law, perpetuating these unethical practices in Australian and international legal contexts.

In particular, we will investigate Telstra's role in this narrative, scrutinizing how influential individuals in governmental roles tolerated and facilitated the company's conduct, which was marked by blatant unethical behaviour. This complicity occurred at various stages: before the arbitration proceedings commenced, throughout the arbitration processes, and even in the aftermath, highlighting a systemic failure to protect the interests of the businesses involved in the COT cases.

This analysis will focus on the actions, or lack thereof, of the arbitrator appointed to oversee the initial four cases. It is essential to comprehend how this individual failed to undertake a comprehensive investigation, jeopardizing the businesses that sought resolution through arbitration. Furthermore, the arbitration financial and technical resource unit, tasked with assisting the arbitrator, was covertly exonerated from any liability for negligence or complicity. This action undermined the foundational principles of fairness and justice, raising significant concerns regarding the integrity of the arbitration process.

Moreover, the clandestine alteration of clause 24 and the removal of clauses 25 and 26 from the agreement sent to the claimant's legal representatives for approval occurred after these accords were faxed and delivered to the offices of two interested Senators. In summary, the COT Cases were never intended to prevail in their claims. Additional information supporting the tampering with the arbitration agreement after it was agreed to is available in Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct.

This detailed recounting of events aims to illuminate significant breaches of trust within the Australian system. It fundamentally challenges the notion of accountability and highlights the profound implications that arise when ethical standards are disregarded in the pursuit of power and profit.

TIO Evidence File No 3-A is an internal Telstra email (FOI folio A05993) dated 10 November 1993 from Chris Vonwiller to Telstra’s corporate secretary Jim Holmes, CEO Frank Blount, group general manager of commercial Ian Campbell and other vital members of the then-government owned corporation. The subject is Warwick Smith – COT cases, and it is marked as CONFIDENTIAL:

“Warwick Smith contacted me in confidence to brief me on discussions he has had in the last two days with a senior member of the parliamentary National Party in relation to Senator Boswell’s call for a Senate Inquiry into COT Cases.

“Advice from Warwick is:

Boswell has not yet taken the trouble to raise the COT Cases issue in the Party Room.

Any proposal to call for a Senate inquiry would require, firstly, endorsement in the Party Room and, secondly, approval by the Shadow Cabinet. …

The intermediary will raise the matter with Boswell, and suggest that Boswell discuss the issue with Warwick. The TIO sees no merit in a Senate Inquiry.“He has undertaken to keep me informed, and confirmed his view that Senator Alston will not be pressing a Senate Inquiry, at least until after the AUSTEL report is tabled.

“Could you please protect this information as confidential.”

Exhibit TIO Evidence File No 3-A provides crucial evidence that just two weeks before the official appointment of the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) as the administrator of the Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP)—which subsequently evolved into the Fast-Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP)—the TIO engaged in providing privileged government part-room confidential information to Telstra. This entity would soon find itself as a defendant in this process. This course of action not only constituted a serious breach of the TIO’s professional duty of care to the Claimant of the COT (Companies and Other Telecommunications cases) but also represented an apparent conflict of interest that compromised his integrity and future role as the so-called independent administrator of the arbitration process.

The TIO’s discussions with Telstra’s senior executives included critical insights regarding the sentiment within Senator Ron Boswell’s National Party room, particularly their lack of enthusiasm for pursuing a Senate inquiry into the COT matters. This insider information likely influenced Telstra's decision-making process, leading them to transition from the original non-legalistic commercial assessment framework of the FTSP to a more defensible legalistic arbitration approach. Armed with the knowledge that the threat of a Senate inquiry was significantly diminished due to the TIO’s disclosures, Telstra felt empowered to pursue a strategy that would better align with their interests and desired outcomes.

How is it possible that Warwick Smith, who served as the administrator of both the settlement and arbitration process, was able to work closely with the defendant in a way that allowed them to acquire critical information from government discussions? This information had the potential to directly influence and alter the outcome of the initial settlement proposals. If such actions are not deemed criminal conduct that facilitated Telstra's claims against us in the four COT cases, then one must question what other category of misconduct would accurately describe this behaviour. Additionally, it raises important concerns as to why numerous government entities have chosen to overlook this blatant conflict of interest. Could this negligence be linked to Warwick Smith's elevation to a front-bench politician during John Howard's government in March 1996? This connection warrants a thorough investigation, considering the implications it holds for fairness in the arbitration process.

Whistleblowing

The Secret State

On 26 September 2021, Bernard Collaery, Former Attorney-General of the Australian Capital Territory (under the heading) The Secret State, The Rule of Law & Whistleblowers, at point 7 of his 12-page paper, noted:

"On some significant issues the Australian Parliament has ceased to be a place of effective lawmaking by the people, for the people. It has become commonplace for Parliamentarians to see a marathon superannuated career out with ideals sacrificed for ambition."

Perhaps the best way to expose this part of the COT story is to use the Australia–East Timor spying scandal, which began in 2004 when an electronic covert listening device was clandestinely planted in a room adjacent to East Timor (Timor-Leste) Prime Minister's Office at Dili, to covertly obtain information to ensure the Liberal Coalition Government held the upper hand in negotiations with East Timor over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap. The East Timor government stated that it was unaware of the espionage operation undertaken by Australia.

The narrative regarding the Casualties of Telstra (COT) presents a significant examination of the hardships endured by individuals who lacked the political connections that benefited certain cases, specifically the "litmus five" COT Cases. These five individuals successfully acquired 150,000 previously withheld freedom of information documents, which are critical to understanding their situation. In addition, they received technical assistance that enabled them to evaluate the importance of these documents, which collectively encompass a staggering 150,000 items.

The impact of this assistance was profound, as the "litmus five" were awarded over 18 million dollars in punitive damages, a substantial sum highlighting the severity of the injustices they faced. In stark contrast, the remaining sixteen COT Cases received no financial compensation, underscoring a significant disparity in treatment. This pattern of discrimination and disregard has continued for years after the completion of the COT arbitration and mediation processes, which reflects a troubling historical precedent from thirty years earlier, when the same Liberal Coalition government dismissed concerns related to the controversial Red Communist Chinese wheat deal, thereby showcasing a recurring theme of neglect for the grievances of affected individuals. (Refer to Chapter 7- Vietnam - Vietcong - British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smiths Seaman.

Illuminating this historical context is essential for readers of my COT narrative to grasp these events' genuine nature fully. The actions taken—or, in some cases, not taken—by Australia’s Liberal Coalition Country Party government illustrate a clear trajectory of injustice, occurring not merely once but on two separate occasions. Understanding this context is essential for recognizing the broader implications of these governmental actions and their ongoing effects on the individuals involved (refer to An Injustice to the remaining 16 Australian citizens). In simple terms, if you have connections in government, you have a better chance of finding justice in Australia than those who do not.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI), but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On pages 23-8 of the letter, Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) clearly provided Sue Laver (the current 2024 Telstra Corporate Secretary) with damning evidence. It shows that Telstra knowingly submitted false information to the Senate Committee on Notice while Ms Laver and Telstra were assuring the chair of the Senate legislation committee that there was nothing wrong with the Bell Canada International Inc. BCI test conducted at Cape Bridgewater (refer also to Confronting Despair)

This false information was provided to the Senate regardless of whether the Senate requested it to be supplied on notice. Additionally, the two documents dated January 1998 (refer to (Scrooge - exhibit 62-Part One confirm that Telstra knew in January 1998 that the Bell Canada International Inc. BCI information, later provided to the Senate in October 1998, had to have been false. It is concerning that no one within Telstra has been held accountable for supplying false Cape Bridgewater Bell Canada International Inc. BCI results to the Senate on notice. Had Telstra not provided this false information to the Senate on notice and acknowledged the accuracy of my claims, the Senate would have addressed all the BCI matters in 1998, the same BCI matters I am now highlighting on absentjustice.com in 2024. Refer to Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2.

After a meticulous review of the compelling evidence connected to DMR Group Inc. (Canada), it has come to my attention that Paul Howell, the esteemed Principal Technical Arbitration Consultant, was sent from Canada with the specific purpose of investigating the technical grievances I raised against Telstra during the years 1994 and 1995. My complaints were centred on the alarming and deceptive practices employed by Telstra, particularly their use of falsified testing results provided by Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) at the Cape Bridgewater Telstra facility. These misleading results persuaded the arbitrator that I was not experiencing any ongoing telephone faults, which was far from the truth.

What adds a layer of distress to this situation is the knowledge the government communications authority possessed regarding Telstra's testing methodologies, which were inadequate for identifying the recurring systemic issues I had reported. This was documented in their AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings dated March 1994 (Refer to points 2 to 212, especially at points 210, 211 and 212, underscoring a troubling disregard for the validity of the tests being conducted

Moreover, neither DMR Group Inc. Canada nor Lane Telecommunications must take any initiative to investigate or resolve the persistent telephone faults that plague my service. In point 2.23 of their report, it is starkly highlighted that the lack of investigation into these ongoing issues left the faults unresolved and "open." The arbitration report dated April 30 suggests that Mr Howell’s journey from Canada was merely a formality to endorse a flawed report that would ultimately lead to the collapse of my business and significantly disrupt my life. This alarming scenario raises profound questions about the ethical integrity of the Canadian telecommunications industry.

I have attached a mirrored copy of the statement in point 2.23, titled Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp Evaluation Report 30 April 1995. File 45-c File No/45-A)

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’ (not my emphasis)

The ongoing reports of 008/1800 faults, which extend to the present day, indicate that the level of disruption to the overall Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp (CBHC) service is still unclear. As the underlying causes of these faults have never been diagnosed, it is reasonable to expect that they remain "open," unresolved, and continued to negatively impact my service until 2006, twelve years after the completion of the arbitration.

In straightforward terms, Telstra, in collaboration with their governmental advisors, successfully engaged two esteemed Canadian telecommunications firms, Bell Canada International Inc. and DMR Group Inc. Canadia, to produce two reports. Rather than accurately documenting the ongoing issues related to my telephone service, these reports presented technical findings that were knowingly misleading. Both companies were aware that their assessments did not truthfully reflect the actual situation, opting instead to conform to the narrative that Telstra sought to establish.

There are discrepancies between the arbitrator’s version and my version of Lane's prepared technical consultant report titled Resource Unit Technical Evaluation Report. Mr Alan Smith. CBHC. 30 April 1995. The second paragraph on page one consists of only one short sentence, “It is complete and final as it is,” (see Arbitrator File No/27). However, the second paragraph on the equivalent page (page two) of the arbitrator’s report, also dated 30 April 1995, says:

“There is, however, an addendum which we may find it necessary to add during the next few weeks on billing, i.e. possible discrepancies in Smith’s Telecom bills.” (See Arbitrator File No/28)

The information on (Arbitrator File No/28) indicates that the appointed arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, prevented his arbitration consultants from investigating the ongoing telephone 008/1800 problems, as outlined in the DMR & Lane segment. When the discussion shifted to Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues, it came to light that DMR & Lane needed additional weeks to address these critical issues thoroughly. Why were these extra weeks not taken to complete the reporting on my claim by DMR & Lane?

Leading up to the arbitration process

My own experience, which I have documented on absentjustice.com and elsewhere, highlights the shortcomings of the arbitration process. For inexplicable reasons, the arbitrator failed to compel Telstra to address the ongoing telephone issues that had initially prompted my case. On 13 April 1994, the government issued clear findings to the arbitrator, stating that Telstra had a duty to demonstrate no lingering telephone problems impacting the services affecting the COT cases that had opted for arbitration.

However, when my arbitration concluded on 11 May 1995, the situation had deteriorated further; the communication issues I faced were more severe than at the outset. The new owners of my business, who acquired it in December 2001, continued to grapple with these unresolved problems until November 2006—an astonishing eleven years after the arbitration ended. Yet, I was granted compensation for losses until the start of my arbitration, leaving me without the full resolution I desperately needed. Refer to Chapter 4, The New Owners Tell Their Story, and Chapter 5, Immoral - Hypocritical Conduct.

Threats made during my arbitration

On July 4, 1994, amidst the complexities of my arbitration proceedings, I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra's arbitration defence team representative. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred an entire month before the arbitrator was legally obligated to share such information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. I poured considerable effort into crafting this detailed letter, carefully choosing every word. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no plans to submit any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardize my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could impact the arbitrator's decisions regarding my case.

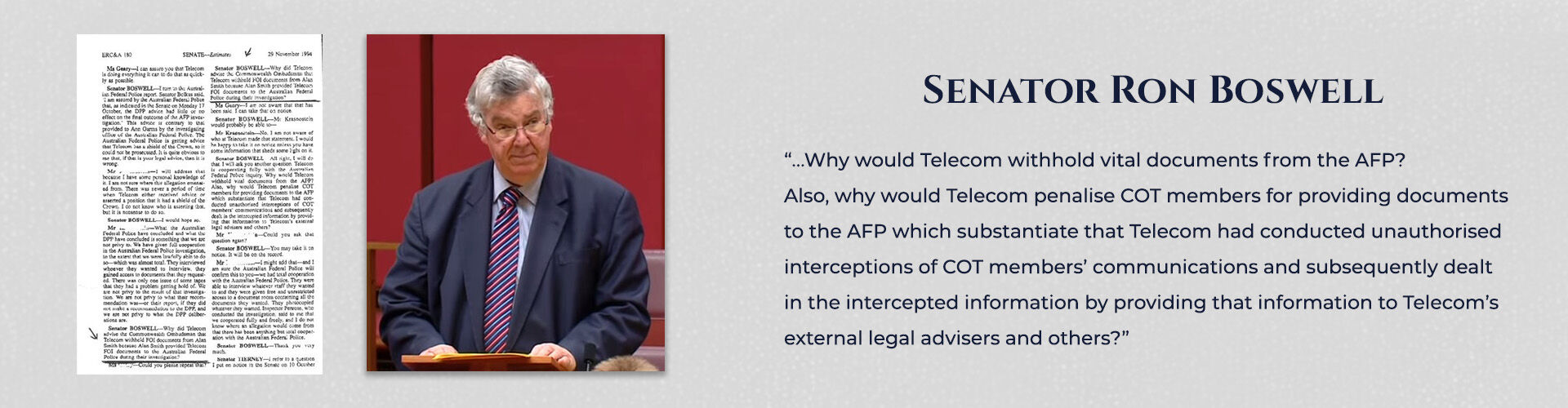

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on September 26, 1994. During this visit, they began to pose probing questions regarding my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result of this situation, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the Senate. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this - no one in the TIO office or government has ever investigated the disastrous impact the withholding of documents had had on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen, who had assisted the AFP in their investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations, was so severely disadvantaged during a civil arbitration.

Pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts provide a comprehensive account establishing Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

Firstly, Mr. Rumble actively obstructed the provision of essential arbitration discovery documents, which the government was legally obligated to provide under the Freedom of Information Act. This obligation was contingent on my signing an agreement to participate in a government-endorsed arbitration process. By imposing this condition, Mr Rumble undermined a legally established protocol, effectively manipulating the process for his benefit and jeopardizing my legal rights.

Secondly, I uncovered that Mr. Rumble had a substantial influence over the arbitrator, resulting in the unauthorized early release of my arbitration interim claim materials. This premature revelation directly conflicted with the timeline stipulated in the arbitration agreement that both Telstra and I had formally signed. Specifically, Telstra gained access to my interim claim document five months earlier than what was permitted under the agreed-upon terms. This breach of protocol violated the integrity of the arbitration process and provided Telstra with an unfair advantage in their response to my claims.

According to the rules governing our arbitration process, Telstra was allocated one month to respond to my claim once it had been submitted in writing as my final claim. Furthermore, the arbitrator was only authorized to release my final claim to Telstra once it was officially confirmed to be complete. The five-month delay in submitting my claim in November 1994 was primarily attributable to Mr. Rumble's deliberate withholding of critical technical information. This information was essential for my consultant, George Close, to effectively demonstrate that the issues with my phone remained unresolved. Mr Rumble threatened to withhold this information because I was actively assisting the Australian Federal Police in investigating Telstra’s unlawful interception of my private phone conversations and faxes without a legal warrant.

As a result of these actions, I found myself constrained to a mere one month to formulate a comprehensive response to Telstra's defence. At the same time, they benefited from an extensive five-month preparation period to address my claim. This imbalance undermined the arbitration process's fairness and significantly impacted my ability to advocate effectively for my rights.

Had Mr Rumble unintentionally stumbled upon sensitive information in my interim claim documents related to my phone and interception issues—details that were shared exclusively with the AFP and that he was not legally entitled to access until my claim was certified complete?

This raises an important question: Did the arbitrator fail to grasp the implications of providing such information, potentially undermining my case? Is this the underlying reason behind Mr. Rumble's aggressive stance in intimidating me concerning my willingness to assist the AFP in their ongoing investigations?

Ms Philppa Smith also stated on page 3 of this letter that Telstra's Steve Black had advised Mr Wynack (the Commonwealth Ombudsman Director of Investigations) that Telstra was vetting the supply of sensitive documents because I had previously released misused them, which had embarrassed Telstra. These documents I had supplied to the AFP exposed Telstra's listening to my telephone conversations, intercepting my faxes, or both.

In straightforward terms, Telstra was selectively vetting the sensitive information that I required to substantiate my claims. This practice hindered the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and the Arbitrator, who were jointly tasked with investigating these claims, from fully validating their legitimacy.

In her correspondence, Ms. Philippa Smith specifies that Warwick Smith, the administrator overseeing the settlement proposal, communicated to her office that the delays encountered during the process were solely due to the actions of Telstra. Nevertheless, this assertion is only partially accurate.

Crucially, the letter does not mention that Warwick Smith was covertly sharing internal government political information that could potentially aid Telstra in their defence against the claims related to the COT Cases. The information provided by Warwick Smith, which Telstra appeared to value highly, was directly causing the delays in resolving these claims.

In March 1994, Ms. Phillipa Smith could not have anticipated that five years later, almost to the day after most of the COT cases, businesses—including mine—would be destroyed by the government-endorsed arbitration and mediation processes.

Not Fit For Purpose

Corrupt practices persisted throughout the COT arbitrations, flourishing in secrecy and obscurity. These insidious actions have managed to evade necessary scrutiny. Notably, the phone issues persisted for years following the conclusion of my arbitration, established to rectify these faults.

Confronting Despair

The independent arbitration consultants demonstrated a concerning lack of impartiality. Instead of providing clear and objective insights, their guidance to the arbitrator was often marked by evasive language, misleading statements, and, at times, outright falsehoods.

Flash Backs – China-Vietnam

In 1967, Australia participated in the Vietnam War. I was on a ship transporting wheat to China, where I learned China was redeploying some of it to North Vietnam. Chapter 7, "Vietnam—Vietcong," discusses the link between China and my phone issues.

A Twenty-Year Marriage Lost

As bookings declined, my marriage came to an end. My ex-wife, seeking her fair share of our venture, left me with no choice but to take responsibility for leaving the Navy without adequately assessing the reliability of the phone service in my pursuit of starting a business.

Salvaging What I Could

Mobile coverage was nonexistent, and business transactions were not conducted online. Cape Bridgewater had only eight lines to service 66 families—132 adults. If four lines were used simultaneously, the remaining 128 adults would have only four lines to serve their needs.

Lies Deceit And Treachery

I was unaware of Telstra's unethical and corrupt business practices. It has now become clear that various unethical organisational activities were conducted secretly. Middle management was embezzling millions of dollars from Telstra.

An Unlocked Briefcase

On June 3, 1993, Telstra representatives visited my business and, in an oversight, left behind an unlocked briefcase. Upon opening it, I discovered evidence of corrupt practices concealed from the government, playing a significant role in the decline of Telstra's telecommunications network.

A Government-backed Arbitration

An arbitration process was established to hide the underlying issues rather than to resolve them. The arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration consultants conducted the process using a modified confidentiality agreement. In the end, the process resembled a kangaroo court.

The Under Belly Of Telstra

AUSTEL investigated the contents of the Telstra briefcases. Initially, there was disbelief regarding the findings, but this eventually led to a broader discussion that changed the telecommunications landscape. I received no acknowledgement from AUSTEL for not making my findings public.

&am

A Non-Graded Arbitrator

Who granted the financial and technical advisors linked to the arbitrator immunity from all liability regarding their roles in the arbitration process? This decision effectively shields the arbitration advisors from any potential lawsuits by the COT claimants concerning misconduct or negligence.<

The AFP Failed Their Objective

In September 1994, two officers from the AFP met with me to address Telstra's unauthorized interception of my telecommunications services. They revealed that government documents confirmed I had been subjected to these violations. Despite this evidence, the AFP did not make a finding.&am

The Promised Documents Never Arrived

In a February 1994 transcript of a pre-arbitration meeting, the arbitrator involved in my arbitration stated that he "would not determination on incomplete information.". The arbitrator did make a finding on incomplete information.

On 15 July 1995, two months after the arbitrator's premature announcement of findings regarding my incomplete claim, Amanda Davis, the former General Manager of Consumer Affairs at AUSTEL (now known as ACMA), provided me with an open letter to be shared with individuals of my choosing. This action underscores the confidence she placed in my integrity and professional character:

“I am writing this in support of Mr Alan Smith, who I believe has a meeting with you during the week beginning 17 July. I first met the COT Cases in 1992 in my capacity as General Manager, Consumer Affairs at Austel. The “founding” group were Mr Smith, Mrs Ann Garms of the Tivoli Restaurant, Brisbane, Mrs Shelia Hawkins of the Society Restaurant, Melbourne, Mrs Maureen Gillian of Japanese Spare Parts, Brisbane, and Mr Graham Schorer of Golden Messenger Couriers, Melbourne. Mrs. Hawkins withdrew very early on, and I have had no contact with her since.

The treatment these individuals have received from Telecom and Commonwealth government agencies has been disgraceful, and I have no doubt they have all suffered as much through this treatment as they did through the faults on their telephone services.

One of the striking things about this group is their persistence and enduring belief that eventually there will be a fair and equitable outcome for them, and they are to admired for having kept as focussed as they have throughout their campaign.

Having said that, I am aware all have suffered both physically and their family relationships. In one case, the partner of the claimant has become seriously incapacitated; due, I beleive to the way Telecom has dealt with them. The others have al suffered various stress related conditions (such as a minor stroke.

During my time at Austel I pressed as hard as I could for an investigation into the complaints. The resistance to that course of action came from the then Chairman. He was eventually galvanised into action by ministerial pressure. The Austel report looks good to the casual observer, but it has now become clear that much of the information accepted by Austel was at best inaccurate, and at worst fabricated, and that Austel knew or ought to have known this at the time.”

After leaving Austel I continued to lend support to the COT Cases, and was instrumental in helping them negotiate the inappropriately named "Fast Track" Arbitration Agreement. That was over a year ago, and neither the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman nor the Arbitrator has been succsessful in extracting information from Telecom which would equip the claimants to press their claims effectively. Telecom has devoted staggering levels of time, money and resources to defeating the claiams, and there is no pretence even that the arbitration process has attemted to produce a contest between equals.

Even it the remaining claimants receive satisfactory settlements (and I have no reason to think that will be the outcome) it is crucial that the process be investigated in the interest of accountabilty of publical companies and the public servants in other government agencies.

Because I am not aware of the exact citrcumstances surronding your meeting with Mr Smith, nor your identity, you can appriate that I am being fairly circimspect in what I am prepared to commit to writing. Suffice it to say, though, I am fast coming to share the view that a public inquiry of some discripion is the only way that the reasons behind the appalling treatent of these people will be brought to the surface.

I would be happy to talk to you in more detail if you think that would be useful, and can be reached at the number shown above at any time.

Thank you for your interest in this matter, and for sparing the time to talk to Alan. (See File 501 - AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541 )

Four months after the arbitrator Dr Hughes prematurely brought down his findings on my matters, and fully aware I was denied all necessary documents to mount my case against Telecom/Telstra, an emotional Senator Ron Boswell discussed the injustices we four COT claimants (i.e., Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan, Graham Schorer and me) experienced prior and during our arbitrations (see Senate Evidence File No 1 20-9-95 Senate Hansard A Matter of Public Interest) in which the senator notes:

“Eleven years after their first complaints to Telstra, where are they now? They are acknowledged as the motivators of Telecom’s customer complaint reforms. … But, as individuals, they have been beaten both emotionally and financially through an 11-year battle with Telstra. …

“Then followed the Federal Police investigation into Telecom’s monitoring of COT case services. The Federal Police also found there was a prima facie case to institute proceedings against Telecom but the DPP , in a terse advice, recommended against proceeding. …

“Once again, the only relief COT members received was to become the catalyst for Telecom to introduce a revised privacy and protection policy. Despite the strong evidence against Telecom, they still received no justice at all. …

“These COT members have been forced to go to the Commonwealth Ombudsman to force Telecom to comply with the law. Not only were they being denied all necessary documents to mount their case against Telecom, causing much delay, but they were denied access to documents that could have influenced them when negotiating the arbitration rules, and even in whether to enter arbitration at all. …

"This is an arbitration process not only far exceeding the four-month period, but one which has become so legalistic that it has forced members to borrow hundreds of thousands just to take part in it. It has become a process far beyond the one represented when they agreed to enter into it, and one which professionals involved in the arbitration agree can never deliver as intended and never give them justice."

"I regard it as a grave matter that a government instrumentality like Telstra can give assurances to Senate leaders that it will fast track a process and then turn it into an expensive legalistic process making a farce of the promise given to COT members and the unducement to go into arbitration. “Telecom has treated the Parliament with contempt. No government monopoly should be allowed to trample over the rights of individual Australians, such as has happened here.”

“Telecom has treated the Parliament with contempt. No government monopoly should be allowed to trample over the rights of individual Australians, such as has happened here.” (See Senate Hansard Evidence File No-1)

Senator Boswell’s statement that: “a point confirmed by professionals deeply involved in the arbitration process itself and by the TIO’s annual report, where conclusion is described as ‘if that is ever achievable’ shows, by the date of this Senate Hansard on 20 September 1995, the TIO had already condemned the arbitration process. So why did John Pinnock (the second administrator to the COT arbitrations) and Dr Gordon Hughes, eight months later, conspire to mislead and deceive Laurie James, President of The Institute of Arbitrators Australia (refer Chapter 3 - The Sixth Damning Letter and Chapter 4 - The Seventh Damning Letter) concerning the truth of my claims, which were registered with the proper authority, i.e., the president of Institute of Arbitrators Australia?

Infringe upon the civil liberties.

Most Disturbing And Unacceptable

On 27 January 1999, after having also read my first attempt at writing my manuscript absentjustice.com, the same manuscript I provided Helen Handbury, Senator Kim Carr wrote:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

An investigation conducted by the Senate Committee, which the government appointed to examine five of the twenty-one COT cases as a "litmus test," found significant misconduct by Telstra. This was highlighted by the statements of six senators in the Senate in March 1999:

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Regrettably, because my case had been settled three years earlier, I and several other COT Cases could not take advantage of this investigation's valuable insights or recommendations. Pursuing an appeal of my arbitration decision would have incurred significant financial costs that I could not afford as shown in an injustice for the remaining 16 Australian citizens.

The six senators mentioned above formally recorded how they believed that Telstra had 'acted as a law unto themselves' leading up to and throughout the COT arbitrations; however, where were Dr Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator) and Warwick Smith (the arbitration administrator) when this disgraceful conduct towards the COT Cases was being carried out?

On 26 September 1997, at the beginning of the Senate Committee hearing that prompted the Senate to start their investigation, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, John Pinnock, who took over from Warwick Smith formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There is no amendment attached to any agreement, signed by the first four COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those particular arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure – and neither was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide under the tainted altered confidentiality agreement (see below) when that agreement did not mention that the arbitrator would have no control over the arbitration because the process would be conducted 'entirely' outside the agreed procedures?

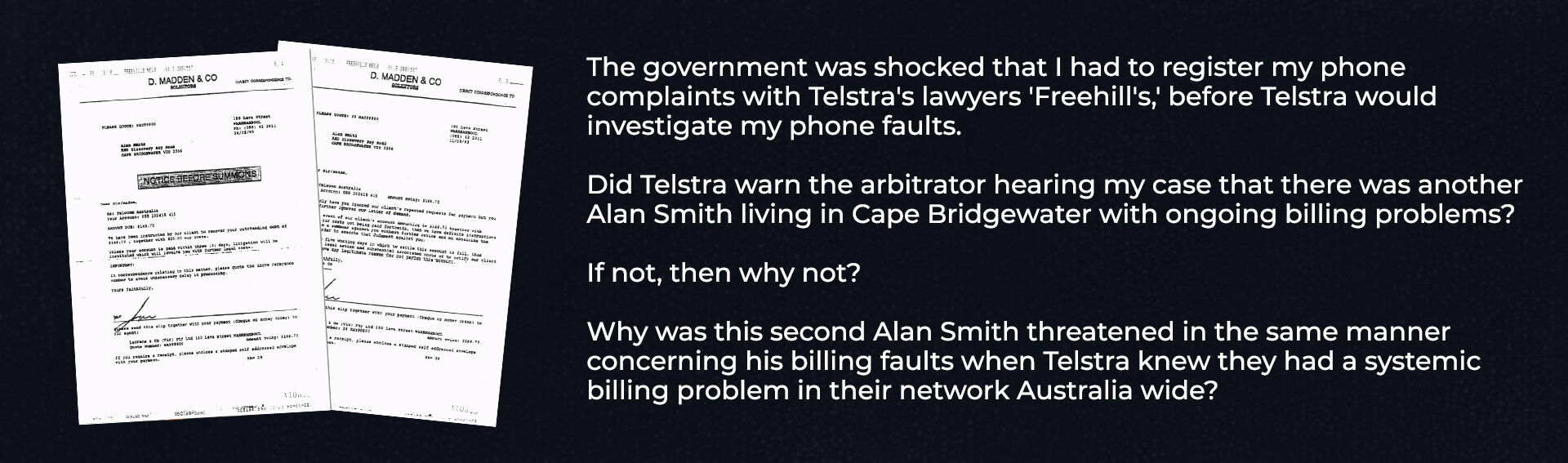

More Threats, this time to the other Alan Smith

Two Alan Smiths (not related) living in Cape Bridgewater.

No one investigated whether another person named Alan Smith, who lived in the Discovery Bay area of Cape Bridgewater, received some of my arbitration mail. Both the arbitrator and the administrator of my arbitration were informed that road mail sent by Australia Post had not arrived at my premises during my arbitration from 1994 to 1995.

Additionally, the new owners of my business lost legally prepared documents related to Telstra when they attempted to send mail to the Melbourne Magistrates Court. I had prepared these documents in a determined effort to prevent them from being declared bankrupt due to ongoing telephone issues. They were sent from the Portland Post Office but did not arrive (Refer to Chapter 5, Immoral—Hypocritical Conduct).

Major Fraud Group - Victoria Police investigation

This chapter explores the significant errors that came to light during the five Senate Estimates committee investigations tied to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, particularly focusing on the flawed Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) testing process. Deficiencies marked this process and, in my experience, proved to be impractical.

From 1994 until at least 2011, Graham Schorer, the spokesperson for the COT Cases, consistently maintained a compelling belief. He recalled an unsettling interaction when he received a phone call from computer hackers in April 1994. During this conversation, they suggested that Telstra was engaged in unlawful conduct. Among these hackers, one prominent individual—whom we now suspect to be Julian Assange—used the term “report” when they discussed certain documents and emails. They tantalizingly offered to provide copies of these materials, claiming they would substantiate their accusations against Telstra’s unlawful behaviour toward us.

This prompts an important question: Did the BCI Cape Bridgwater tests, referenced by Julian Assange, provide evidence of Telstra’s illicit actions? Neil Jepson, a barrister representing the Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police, has stated unequivocally that this report was false. He contended that for Telstra to utilize it as part of their defence strategy in arbitration—specifically, by presenting it to Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist—was inappropriate. This occurred just before Joblin met with me, inquiring if my concerns regarding ongoing telephone issues stemmed from paranoia.

When we discussed these hackers with Neil Jepson, Julian Assange had not yet emerged as a significant figure in the public eye. The BCI reports were paramount to the Major Fraud Group’s investigation, so Victoria Police sought my assistance in their fraud inquiry into Telstra's activities.

During this period, all members involved in the COT cases were willing to remain patient, convinced that the investigation into the litmus cases would eventually influence the other 16 cases listed on Senate Schedule B. However, as the investigation progressed, none of the 16 COT cases were updated about its status. John Wynack, the director of investigations who was aiding the Senate chair with the litmus cases, was simultaneously examining my FOI issues. He demanded that Telstra initially provide the documents I had requested in my FOI submission dated October 18, 1995.

While the litmus test cases garnered an impressive volume of approximately 150,000 FOI documents through the Senate Estimates Committee investigation, I found myself in a frustrating position: I received not a single document. Wynack's own records from March 11 and 13, 1997, reveal that he did not accept Telstra's claim that they had destroyed the arbitration file essential for my ongoing appeal process.

This troubling situation was precisely the kind of misconduct that Julian Assange attempted to warn us about about the COT cases, yet we failed to heed his advice. Had we taken his warnings seriously, our lives might have avoided the detrimental impacts we have endured.

The remaining COT cases, bearing names on the Senate Schedule B, similarly sought FOI documents from Telstra amid their own arbitration and mediation efforts, just as the litmus test cases had. The Senate was well aware of this situation, so a litmus test framework was instituted. The litmus test cases are enumerated on Senate Schedule A, while Schedule B lists the other 16 cases. If the litmus test cases established that Telstra had improperly withheld essential documents during their arbitration processes, the remaining 16 cases would have been poised to receive an equivalent outcome.

Nevertheless, the treatment of the Australian litmus cases starkly contrasted with that of the 16 other Australian citizens who faced dismissal. The rationale for this disparate treatment is clear: it stemmed from political dynamics and the passage of time. It took nearly two years, involving the concerted efforts of numerous senators, to obtain the necessary documents for the five litmus cases. Some observers believe that the looming privatization of Telstra may have played a significant role in the dismissive attitude toward the remaining 16 cases. This situation represents a grave instance of discrimination against these 16 Australian citizens, highlighting systemic failures that continue to resonate today.

Litmus Tests

The coalition LNP government should have fully acknowledged its profound constitutional and ethical obligation to represent and serve all citizens without prejudice rather than disproportionately favouring those individuals with established government influence. It is paramount for all relevant parties, including the COT Cases, to be treated with the utmost fairness and equity under the law. Regrettably, this fundamental principle was not upheld when the government denied the remaining 16 citizens access to the same comprehensive legal remedies and justice measures afforded to the five litmus test cases.

This failure is particularly alarming given the multiple warnings and advisories received by the government concerning the grave injustices that Julian Assange later brought to light. These warnings unfolded over an extended period from June 1997 to September 1999. The injustices initially highlighted by Assange during his discussions with COT Cases spokesperson Graham Schorer in 1994 are substantiated by meticulous records found in the Senate Hansard dated June 24 and 25, 1997. These official documents serve as crucial evidence, demonstrating the government's awareness of the legal ramifications associated with its actions and decisions. Refer to (1) Senate - Parliament of Australia and:- (2) SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia

The coalition LNP government should have fully acknowledged its profound constitutional and ethical obligation to represent and serve all citizens without prejudice rather than disproportionately favouring those individuals with established government influence. It is paramount for all relevant parties, including the COT Cases, to be treated with the utmost fairness and equity under the law. Regrettably, this fundamental principle was not upheld when the government denied the remaining 16 citizens access to the same comprehensive legal remedies and justice measures afforded to the five litmus test cases.

This situation is particularly concerning in light of the numerous warnings and advisories the government received regarding the grave injustices affecting three computer hackers—presumed to be Julian Assange since there has been no official confirmation from the government. Their communication emerged in April 1994, as the first four COT arbitrations began. During this crucial period, all four parties executed their arbitration agreements: Maureen Gillan signed on April 8, 1994, while Ann Garms, Graham Schorer, and I followed suit on April 21, 1994.

Over the years, various authoritative sources issued warnings, neglecting to take decisive action. These included the hackers, the Australian Federal Police in 1995, and the Quest Private Detective Agency in Melbourne in January 1996. The Senate and the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman raised concerns in 1997, and the Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police joined in alerting the public in 1998. The Senate reiterated these warnings in 1999, followed by an essential message from ex-senior principal Telstra Protective Officer Des Direen in August 2006. Finally, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal weighed in as well in 2008. This alarming sequence of warnings unfolded over many years.

These documents serve as crucial evidence, demonstrating the government's awareness of the legal ramifications associated with its actions and decisions. Furthermore, the LNP government was acutely aware that the litmus test cases were not the only individuals entitled to receive the critical documents pertinent to their legal cases; the other 16 citizens equally deserved such access, which is an essential aspect of justice.

The Senate Hansard records issued within three days distinctly confirm that Telstra Corporation engaged in unlawful practices against all 21 citizens involved. Despite this compelling evidence, the government inexplicably authorized financial compensation solely for the litmus test cases, thereby systematically excluding the other 16 individuals who were also victims of this injustice. The litmus test cases, consequently, benefitted from access to over 150,000 previously withheld discovery documents, which played a crucial role in enabling them to appeal the outcomes of their arbitration processes. In stark contrast, the remaining 16 citizens were left without the necessary documentation, rendering them powerless to pursue legal recourse or appeal.

Moreover, compelling evidence from Senate Evidence File No 12, indicates that I have faced direct threats on two separate occasions—first on August 16, 2001, and again on December 6, 2004. During these tense moments, I was expressly warned that should I disclose the In-Camera Hansard records from July 6 and July 9, 1998, I would face serious charges of contempt against the Senate. This warning is particularly vexing, given that these records contain vital information that could facilitate successful arbitration and mediation appeals for the 16 citizens who were unjustly deprived of legal redress.

This troubling situation raises a critical question: Where is the justice in threatening imprisonment against individuals striving to expose the truth regarding unethical conduct directed at the COT Cases? Such actions appear to starkly contradict the core values and responsibilities that underpin the very purpose of the Senate in Australia. I am concerned about the potential repercussions of publicly disclosing these In-Camera Senate Hansard records from July 6 and 9, 1998. These records were provided to me by the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group, which believed that the dissemination of this information could catalyze an appeal on behalf of the remaining sixteen COT Cases. Regrettably, these individuals have endured treatment that is not only unjust but also demands unequivocal recognition and corrective action to address the inequities they have faced.

An intense confrontation in a heated Senate committee meeting unfolded when National Party Senator Ron Boswell unleashed a fiery critique towards a senior officer involved in the Telstra arbitration process. With palpable frustration, he exclaimed, “You are really a disgrace, the whole lot of you,” his voice resonating throughout the chamber. The remarks cast a shadow over the already tense atmosphere as Telstra's conduct regarding the COT Cases took centre stage.

However, the gravity of his words quickly caught the attention of the committee chair, prompting a swift intervention. Under scrutiny and recognizing the need for decorum in such a serious forum, Senator Boswell was compelled to offer an apology. Turning to the chairperson more measuredly, he declared, “Madam, I withdraw that remark.” This moment of accountability underscored the importance of respectful dialogue in legislative discussions and illuminated the ongoing challenges surrounding Telstra’s treatment of COT Cases, a matter of significant public interest.

“Madam, I withdraw that, but I do say this: this has got a unity ticket going right through this parliament. This has united every person in this parliament – something that no-one else has ever had the ability to do – and Telstra has done it magnificently. They have got the Labor Party, they have got the National Party, they have got the Liberal Party, they have got the Democrats and they have got the Greens – all united in a singular distrust of Telstra. You have achieved a miracle.”

A Labor Party Senator, Chris Schacht, even made it more apparent to the same Telstra arbitration officer that if Telstra were to award compensation only to the five 'litmus' COT test cases and not the other still unresolved issues, then this act "would be an injustice to those remaining 16". However, the John Howard National Liber Part NLP government sanctioned punitive damages to those five litmus test cases, plus the release of more than 150,000 Freedom of Information documents initially concealed from those five COT Cases during their government-endorsed arbitration of 1994 to 1998. The eighteen million dollars those five received between them should have been split equally between all twenty-one unresolved COT Cases FOI issues. It was not.

Will I go to jail in 2024 for revealing this gross discriminative act by an Australian government against sixteen fellow citizens? I believe the current Labor government, if they were to ask me to provide a government-appointed representative to view these two In-Cameral Hansards of 6 and 9 July 1998, that representative would advise the Anothony Albenise government they are morally obliged to pay compensation as former Labor Senator Chris Schacht stated should have been the case in 1998. Sadly, at least three of those sixteen have since died.

Before I proceed further with this Senate matter, it is essential to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the situation involving the Telstra arbitration officer, who became the target of Senator Ron Boswell's intense frustration and anger. This particular individual was not merely a senior executive at Telstra; he also held an influential position as a Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO Council) member. This council was crucial in managing the COT arbitrations intended to ensure fair treatment for customers.

What raises serious ethical concerns is that this Telstra executive violated his fiduciary duties by sharing confidential information discussed in TIO Council meetings with his superiors at Telstra. Such information was strictly classified and meant to be kept within the confines of the council, highlighting a severe breach of trust that undermined the integrity of the arbitration process.

Moreover, during a significant Senate debate on September 26, 1997, this same Telstra arbitration officer made a startling admission. He revealed that he had participated in numerous TIO Council meetings where the trajectory and progress of the COT arbitrations were regularly discussed. At this pivotal hearing—which sought to investigate the questionable treatment of the COT arbitrations—he openly admitted that he failed to disclose his conflict of interest while attending these meetings. This lack of transparency questioned the legitimacy of the arbitration process and raised serious doubts about the fairness of the proceedings.

In the context of Senator Ron Boswell’s impactful statements, which resulted in our organization issuing a public apology, it is important to grasp the events leading to his remarks. On November 29, 1994, amid the unfolding events of my arbitration case, Senator Boswell boldly took a stand and demanded answers from Telstra's legal Directorate. His inquiries were pointed and direct: he wanted to understand why Telstra had resorted to issuing threats against me. Specifically, if I did not cease my cooperation with the Australian Federal Police in their ongoing investigation into Telstra's unauthorized interception of my private telephone conversations and essential fax documents related to my arbitration claim, they would cut off access to the critical documents that I needed to support my case.

The correspondence addressed to the Commonwealth Ombudsman reveals a troubling injustice that has affected the remaining 16 Australian citizens involved in the Change of Tenancy (COT) claims. Notably, this correspondence includes input from several technical experts appointed via a Senate working party tasked with evaluating the relevance of Freedom of Information (FOI) documents that the ‘Five Litmus COT claimants’ requested during the Senate investigation.

A significant document among these communications is a comprehensive 14-page letter from Qyncom IT & T Business Consultants Pty Ltd, based in Victoria. This letter was directed to Mr. John Wynack, the working party chair (as referenced in Senate Evidence File No 13A & 13B).

This letter and numerous others submitted to the Commonwealth Ombudsman reveal that the ‘Five Litmus COT claimants’ were afforded considerable advantages. They received free, qualified technical support from independent consultants appointed by the government, which greatly assisted them throughout the lengthy sixteen-month investigation into FOI requests, which the Liberal Government enforced.

In stark contrast, the remaining 16 claimants, also noted on the Senate Schedule as having unresolved COT issues, were systematically denied access to these same levels of assistance and expertise. This glaring discrepancy raises serious concerns about fairness and equity. If this situation does not constitute one of the worst forms of discrimination, what indeed does?

Senate Schedule A and B list

It is imperative to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the possibility that additional factors—potentially a second or even a third reason—contributed to the denial of compensation for the remaining cases linked to 16 COT. These cases, which have experienced unfavourable outcomes, stand in contrast to those awarded compensation in the litmus test cases. A detailed analysis of the reasons for these discrepancies could yield significant insights that might illuminate the underlying issues.

Furthermore, it is crucial to anticipate the types of inquiries that the larger cohort of 21 claimants may raise once the sale prospectus is finalized. Addressing a subset of the outstanding arbitration claims that have remained unresolved for four years, before the preparation of the prospectus, would not only provide clarity regarding the overall claim situation but also bolster the integrity and credibility of the claims process. Presenting a record with fewer unresolved issues will undoubtedly enhance the perceived fairness of the proceedings compared to a scenario in which 21 arbitration claims remain outstanding.

The depth of this matter is magnified by the fact that 16 claimants are still waiting for the relevant discovery documents. These documents are essential as stipulated under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act, which was agreed upon as part of the procedural stipulations before initiating the arbitration proceedings. This agreement mandated that the administrator provide these crucial documents to support the claimants in substantiating their cases (refer to Arbitrator File No/71 for details).

It is also essential to highlight the government's awareness of Telstra's ongoing refusal to fulfil its obligation to provide the necessary documents throughout the litmus test process, which has continued even four years later. On October 23, 1997, the office of Senator Schacht, serving as the Shadow Minister for Communications, transmitted a fax to Senator Ron Boswell containing the proposed terms of reference for a Senate working party. This group was explicitly assigned to investigate the FOI issues relevant to the COT arbitration cases. The document not only outlines the findings but also delineates two extensive lists of unresolved COT cases that require further investigation concerning their respective FOI issues. Notably, my name appears on Schedule B of that document (see Arbitrator File No 67).

By consistently refusing to provide the 16 COT cases with the discovery documents initially requested four years ago, Telstra has undeniably acted contrary to the principles of the rule of law. This refusal is particularly concerning because these 16 claimants have not received any assistance from law enforcement, arbitrators, or government officials. As a direct result of this inaction, they have been denied access to critical documents needed for their claims. This alarming situation has been documented on absentjustice.com, highlighting the urgent need for accountability, transparency, and justice.

150,000 FOI Documents

The 150.000 late provided FOI documents to the five litmus test cases mentioned above were not historic in the case of Ann Garms and Graham Schorer; the forty-four large storage boxes that I received from Graham’s office in 2006 when I started to investigate these issues on behalf of Graham/Golden messenger I did not see any relevant Leopard or Ericsson Data for the exchanges that Graham’s Golden Messenger Courier Services were routed through. Between the end of 2006 and 2017, I have worked continually on some eight significant projects on behalf of Graham/Golden, who had commissioned me to investigate evidence they had received which showed Telstra had been aware before Graham’s arbitration process that Telstra had knowingly misled both Graham/Golden and the COT arbitrator concerning Graham/Golden 1994 to 1999 arbitration process.

Since that period, I have collated and written five major reports plus two separate manuscripts (not yet completed) so that Graham/Golden can submit this material to the government as a testament; there needs to be a Royal Commission Investigation into the COT arbitration process. During my first Administerial Appeals Tribunal FOI oral hearing in October 2008, the Australian Communications Media Authority (ACMA) was the respondent; Graham Schorer advised the AAT under oath during cross-examination by ACMA lawyers that once my investigation on behalf of Golden was complete and the evidence collated and reported on was bound into submission, those reports would be provided to the government.

Since that 2008 AAT hearing, I have viewed numerous COT Case Telstra-related documents, which support Graham/Golden's claim that even though members of the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman office (who were the administrators of the COT arbitrations) had been aware before the COT Cases went into arbitration that the historic Telstra fault data that would be needed by the COT Cases to support their claims had already been destroyed (see TIO Evidence File No 7-A to 7-C), this knowledge was never broadcast to the government, which had endorsed the COT arbitrations.

This release of 150,000 non-historic fault data documents, NOT the requested historical data, which the five ‘litmus’ test cases requested, shows that the compensation the five litmus cases received was partly associated with Telstra's inability to provide those five cases with the documents they should have received during their arbitrations.

The fact that none of the sixteen COT Cases were also on the Senate Schedule B list as unresolved COT FOI Cases is further testament to the government's discrimination against us in COT sixteen.

To be continued