Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers.

I needed to use the following BCI narrative to introduce my homepage on absentjustice.com. Although the Australian government endorsed my arbitration, which is the foundation of my story, they provided no support when they learned that Telstra, a government-owned entity, used the fundamentally flawed BCI Cape Bridgewater as evidence. This was claimed to support their assertion that Telstra's infrastructure was of world-class standard, as reported by Bell Canada International in the government's first of three legislative sales in 1997. However, the testing equipment used by Bell Canada was not utilized in the telephone exchanges that Bell Canada and Telstra reference.

The only response I have received regarding this grave denial of justice, which the Australian government has allowed to persist for thirty years to my detriment, has come from the Canadian government.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On pages 23-8 of the letter, Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) provided Sue Laver (the current 2025 Telstra Corporate Secretary) with damning evidence. It shows that Telstra knowingly submitted false information to the Senate Committee on Notice while Sue Laver and Telstra were assuring the chair of the Senate legislation committee that there was nothing wrong with the BCI test conducted at Cape Bridgewater.

This false information was provided to the Senate regardless of whether the Senate requested it to be supplied on notice. Additionally, the two documents dated January 1998 (refer to (Scrooge - exhibit 62-Part One confirm that Telstra knew in January 1998 that the BCI information, later provided to the Senate in October 1998, had to have been false. It is concerning that no one within Telstra has been held accountable for supplying false Cape Bridgewater BCI results to the Senate on notice. Had Telstra not provided this false information to the Senate on notice and acknowledged the accuracy of my claims, the Senate would have addressed all the BCI matters in 1998 (Refer to Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2), the same BCI matters I am now highlighting on absentjustice.com in 2025.

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government possessed complete ownership of the nation’s telephone network and the communications carrier known as Telecom, which has since been privatized and rebranded as Telstra. During this period, Telecom maintained a monopoly on telecommunications, exercising unchecked control and allowing the network’s infrastructure to deteriorate substantially. This neglect resulted in inadequate telephone services, which should have been remedied through a government-endorsed arbitration process. However, this process evolved into a challenging and uneven struggle for claimants, many of whom faced insurmountable obstacles. Regardless of the substantial financial burdens, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars, incurred while pursuing their claims against this government-owned entity.

Corruption ran rampant within Telstra's financial practices, fostering a culture of deceit that undermined public trust. When the government wholly owned Telstra, siphoning funds from the public purse became increasingly insidious, leading to many complications that hindered the resolution of the COT Case matters. Doubts regarding Telstra’s integrity and commitment to operating on a level playing field permeated every sector of society, blurring the lines between public expectations and private enterprise.

The second book mentioned in the image below is taking longer to complete than I anticipated. However, I have published some chapters on this homepage, though they may not be in chronological order. These chapters aim to give visitors to absentjustice.com insight into what life was like in Australia thirty years ago, before the advent of emails, computers, and mobile phones—technologies that businesses rely on today.

I am Alan Smith, and I wish to present my prolonged conflict with a telecommunications corporation and the Australian Government. This struggle has evolved since 1992, encompassing various elected governments, government departments, regulatory institutions, the judiciary, and the telecommunications giant Telstra, known initially as Telecom. My pursuit of justice remains ongoing.

This narrative began in 1987 when I decided to transition from a life spent at sea, where I had dedicated 28 years, to a new land-based career. I sought a viable occupation to support my retirement years and beyond. Among the numerous picturesque locations I visited, I chose Cape Bridgewater in Portland, Victoria, Australia, as my new home.

My professional background is in hospitality, and I always aspired to operate a school holiday camp where children could engage with nature and forge lasting friendships. Thus, I was thrilled to discover the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre advertised for sale in The Age newspaper. Conveniently located in rural Victoria, near the scenic maritime port of Portland, this opportunity appeared ideal.

I diligently conducted thorough research to ascertain the viability of the business. However, in my eagerness, I inadvertently overlooked a critical element: the functionality of the telephone service. Within a week of assuming ownership, I identified a significant issue: clients and suppliers began reporting failed attempts to connect via telephone. I found myself managing a business with a phone service that was, at best, inconsistently reliable and, at worst, absent. Consequently, we experienced a detrimental loss of business.

The holiday camp (my business) heavily relied on landline phones as the only means of communication except for passing trade. When we first fell in love with the place, we overlooked the outdated telephone system. In those days, there was no mobile coverage, and business was not conducted through the Internet or email. The camp was connected to a roadside switching facility, which was then routed to the central telephone exchange in Portland, 20 kilometres away. This facility, installed over 30 years ago, was designed for low-call-rate areas and had only eight lines to serve 66 families, totalling 132 adults and children.

If four callers were trying to connect to or from Cape Bridgewater, there were only four available lines for the remaining 128 adults and their children to make or receive calls. During peak times—such as weekends and holidays—when more visitors flocked to the seaside resort, the demand for calls increased significantly. This often resulted in the lines becoming jammed and non-responsive

The document dated March 1994 (AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) unequivocally confirms that between Points 2 and 212, government public servants validated my claims against Telstra in their investigation of my ongoing telephone problems. If the arbitrator had reviewed AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, the financial award for my business losses would have been substantially higher. My claim lacked the comprehensive log over the six-year period that AUSTEL utilized to support their findings, as shown in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

Furthermore, government records (Absentjustice-Introduction File 495 to 551) reveal that AUSTEL's adverse findings were provided to Telstra (the defendants) a month before our arbitration agreement. I received these crucial findings only on November 23, 2007, a staggering 12 years after the conclusion of my arbitration. This delay prevented me from using the government findings to appeal the arbitrator's award due to the expiration of the statute of limitations. It's unacceptable that such important information was withheld for so long.

In this part of my COT story, I aim to help you, the reader, understand how both Australia in the past and Australia in 2025 have seen the government and its highly paid public servants treat ordinary Australians, such as the COT Cases, with absolute contempt. Below, I’ve highlighted seven out of the 212 points from a secret government report that was withheld from me in order to protect the then-government-owned asset, Telstra. Reading all 212 points could bring a tear or two to your eyes.

(AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) at points 46, 47, 109, 115, 130, 153 and 209, respectively, state:

Point 46 –“File evidence clearly indicates that Telecom at the time of settlement with Mr Smith had not taken appropriate action to identify possible problems with the RCM . It was not until a resurgence of complaints from Mr Smith in early 1993 that appropriate investigative action was undertaken on this potential cause In March 1993 a major fault was discovered in the digital remote customer multiplexer (RCM) providing telephone service to Cape Bridgewater holiday camp. This fault may have been existence for approximately 18 months. The Fault would have affected approximately one third of subscribers receiving a service of this RCM. Given the nature of Mr Smith’s business in comparison with the essentially domestic services surrounding subscribers, Mr Smith would have been more affected by this problem due to the greater volume of incoming traffic than his neighbours.”

Point 47 –“Telecom's ignorance of the existence of the RCM fault raises a number of questions in regard to Telecom's settlement with Smith. For example, on what bases was settlement made by Telecom if this fault was not known to them at this time? Did Telecom settle with Mr Smith on the bases that his complaints , of faults were justified without a full investigation of the validity of these complaints, or did Telecom settle on the basis of faults substantiated to the time of settlement? Wither criteria for settlement would have been inadequate, with the later critera disadvantaging Mr Smith, as knowledge of the existence of more faults on his service may have led to an increase in the amount offered for settlement of his claims".

Point 109 – The view of the local Telecom technicians in relation to the RVA problem is conveyed in a 2 July 1992 Minute from Customer Service Manager – Hamilton to Managers in the Network Operations and Vic/Tas Fault Bureau:

- “Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnecte. They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE. (AXE – Portland telephone exchange)”

Point 115 –“Some problems with incorrectly coded data seem to have existed for a considerable period of time. In July 1993 Mr Smith reported a problem with payphones dropping out on answer to calls made utilising his 008 number. Telecom diagnosed the problem as being to “Due to incorrect data in AXE 1004, CC-1. Fault repaired by Ballarat OSC 8/7/93, The original deadline for the data to be changed was June 14th 1991. Mr Smith’s complaint led to the identification of a problem which had existed for two years.”

Point 130 – “On April 1993 Mr Smith wrote to AUSTEL and referred to the absent resolution of the Answer NO Voice problem on his service. Mr Smith maintained that it was only his constant complaints that had led Telecom to uncover this condition affecting his service, which he maintained he had been informed was caused by “increased customer traffic through the exchange.” On the evidence available to AUSTEL it appears that it was Mr Smith’s persistence which led to the uncovering and resolving of his problem – to the benefit of all subscribers in his area”.

Point 153 –“A feature of the RCM system is that when a system goes “down” the system is also capable of automatically returning back to service. As quoted above, normally when the system goes “down” an alarm would have been generated at the Portland exchange, alerting local staff to a problem in the network. This would not have occurred in the case of the Cape Bridgewater RCM however, as the alarms had not been programmed. It was some 18 months after the RCM was put into operation that the fact the alarms were not programmed was discovered. In normal circumstances the failure to program the alarms would have been deficient, but in the case of the ongoing complaints from Mr Smith and other subscribers in the area the failure to program these alarms or determine whether they were programmed is almost inconceivable.”

Point 209 – “Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

It was our fault, not Telstra's

Sometimes, the culprit was blindingly obvious. I was soon labelled a vexatious litigant, and my claims frivolous. On a shopping expedition to Portland, 20 kilometres away, I discovered I had left the meat order list behind. I phoned home from a public phone box, only to get a recorded message telling me the number was not connected! I phoned again to hear the same message. Telstra's fault centre said they would look into the matter, so I went about the rest of the shopping, leaving the meat order to last. Finally, I phoned the Camp again, and the phone was engaged this time. I decided to buy what I could remember from the list and hope for the best; however, I was not surprised when I got home to learn the phone had not rung once while I had been out.

Anyone who uses a telephone has at some time reached a recorded voice announcement (known within the industry as RVA): 'The number you have called is not connected or has been changed. Please check the number before calling again. You have not been charged for this call.' This incorrect message was the RVA people most frequently reached when trying to ring the Camp. While Telstra never acknowledged what I later discovered among 1994 FOI documents, an internal Telstra memo stating: -

'This message tends to give the caller the impression that the business they are calling has ceased trading, and they should try another trader.' AS-CAV Exhibit 1 to 47

Another Telstra document referred to the need for

a very basic review of all our RVA messages and how they are applied … I am sure when we start to scratch around, we will find a host of network circumstances where inappropriate RVAs are going to line. AS6 file AS-CAV Exhibit 1 to 47

For a newly established business like ours, this was a major disaster. Still, despite the memo's acknowledgement that such serious faults existed, Telstra never admitted the existence of a fault in those first years. And with my continued complaints, I was treated increasingly as a nuisance caller. This was rural Australia, and I was supposed to put up with a poor phone service — not that anyone in Telstra was admitting that it was poor service. In every case, 'No fault found' was the finding by technicians and linesmen.

The frustration was immense, coupled with uncertainty. Were our problems no more than general poor rural service compounded by the congestion on too few lines going into an antiquated exchange? At that stage, the Camp was the only accommodation business in Cape Bridgewater. We relied on the phone more than most people in the area. But if there was some specific fault, why weren't the technicians finding it?

The business was in trouble, and so were we. By mid-1989, we were reduced to selling some shares to cover operating costs. Here we were, a mere 15 months after taking over the business, beginning to sell off our assets instead of reducing the mortgage. I felt like a total failure. Neither of us was able to lift the other's spirits.

I decided to do another round of marketing in the city. I would give it all I had. We both went. Was it masochism that made me ring the Camp answering machine via its remote access facility to check for any messages so I could respond promptly? Whatever it was, all I could get was the recorded message: '

The number you are calling is not connected or has been changed. Please check the number before calling again. You have not been charged for this call.'

On the way home, just outside Geelong, we stopped at a phone box, and I tried again. Now, the line was engaged. Perhaps somebody was leaving a message, I thought. Ever hopeful.

There were no messages on the answering machine, and nothing could be gained by asking why I had received an engaged signal. How many calls had we lost during the days that we were away? How many prospective clients had given up trying to get through because a recorded message told them the phone was not connected? Anger and frustration were very close to the surface.

Near the end of October 1989, our twenty-year marriage ended. I had already been taking prescribed drugs for stress; that afternoon, I added a quantity of Scotch and hunkered down in one of the cabins. Faye, understandably, was seriously concerned and called the local police, who broke into the cabin to 'save' me from me. They took me to a special hospital, and I am forever grateful to the doctors who confirmed that I wasn't going 'nuts' and who sent me home the following day.

When I took refuge in the cabin on the afternoon of 26 October 1989, only to find my refuge attacked by a Police rescue team, I was transported straight back to The People's Republic of China in July and August 1967 (Refer to British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smiths Seaman. After some heavy discussions with my wife and my ‘saviours’ who, in my confused state, seemed more like the Red Guard soldiers than anything else, I was taken to hospital — in a straight jacket.

I will be forever grateful to the doctors who confirmed that I wasn’t going ‘nuts’ and who allowed me to return to the camp the following day, accompanied by my mate’s wife, Margaret. I will also be forever grateful to Jack for sending Margaret to ‘bail me out’ so to speak. The fun, however, had just begun.

At this point, I need to fill in some details regarding an incident in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution in China. At that time, many young Australians were supporting the American fight against Communism in Vietnam, and this young man was sailing with the Merchant Marines. We were headed to Communist China from Port Albany in Western Australia with a cargo of wheat, although the Australian Labor Party was against our ship leaving. Flash Backs – China-Vietnam highlights a brief explanation of this China issue.

I began to keep a log

In the weeks that followed, my phone problems continued unabated. I began keeping a log of phone faults, recording all complaints I received in an exercise book, along with names and contact details for each complaint and a note regarding the effect these failed calls had on the business and me.

One day, the phone extension in the kiosk died. The coin-operated gold phone in the dining room, which was on a separate line, had a normal dial tone, so I dialled my office number, only to hear the dreaded:

'The number you have called is not connected or has been changed. Please check the number before calling again. You have not been charged for this call.'

I was charged for the call because the phone didn’t return my coins. Five minutes later, I tried again. This time, the office phone appeared to be engaged (even though I was the only person at the holiday camp), but the gold phone happily returned my coins. Was I going crazy? I questioned my sanity many times from 1989 through August 1992, when I helped establish a self-help group called “Casualties of Telstra.”

Yes, some calls did get through; I shall never know in what proportion, though perhaps the rate is indicated by the following story. In desperation, I decided to ring Don Burnard, a clinical psychologist the COT members had contacted when we started creating the group. Dr Burnard had written a report regarding our conditions, noting the breakdown in our psychological defences due to the excessive and prolonged pressures we endured:

All of these clients have been subjected to persistent environmental stress as a result of constant pressure in their business and erratic patterns of change in the functioning of their telephones which were essential to the success of their businesses.

I rang Dr Burnard for support, but phone faults interrupted my conversation with his receptionist three times. Later, I received a letter from his office, saying:

I am writing to you to confirm details of telephone conversation difficulties experienced between this office and our residence mid-morning this day, 5 May 1993. At approximately 11.30 am today Mr Alan Smith telephoned this office requesting to speak with Don Burnard. Mr Burnard was not available to take his call. During this time the telephone cut out three times. Each time Mr Smith telephoned back to continue the call.

Despite the enterprise's financial precariousness, I had initially sponsored the stays of underprivileged groups at the Camp. It was no loss to me: sponsored food was provided through the generosity of several commercial food outlets, and it cost me only a small amount of electricity and gas.

In May 1992, we held a charity week for kids from Ballarat and South-West Victoria, organised mainly by Sister Maureen Burke, IBVM, Principal of Loreto College in Ballarat. Arrangements regarding food, transport, and any special needs the children might have had to be handled over the phone, and of course, Sister Burke had enormous problems making phone contact. The Calls were either ringing out, or she was getting a deadline — no sound at all. Finally, after trying in vain for one week, she decided to drive the 3½ hours to make the final arrangements.

Testimonials

Between April 1990 and when I sold the holiday camp in December 2001, I continued to partly sponsor underprivileged groups who wished to avail themselves to the facilities at the holiday camp during the weeks (that became years) when the phone problems continued to beset the venue. At least some money was coming into the business. Those wanting a cheap holiday persisted by telephoning repetitively regardless of being told the camp was no longer connected to Telstra's network. These groups wanted a holiday, and if they had to drive for hours to make a booking as Loreto College did (see below), then a drive they did.

The holiday Camp could sleep 90 to 100 people in fourteen cabins. When the charity group organised by Sister Maureen Burke IBVM, the Principal of Loreto College in Ballarat, finally arrived, the whole week became a great success for all concerned; all enjoyed the in-camp activities, canoeing, and horse riding on the beach. I am sure she would not be offended to know that I think of her as the ‘mother’ of the project.

Arrangements regarding food, transport, and any special needs the children might have had to be handled over the phone, and of course, Sister Burke had enormous problems making phone contact; calls were either ringing out, or she was getting a deadline or a message that the number she was ringing was not connected to the Telstra network. Sister Burke knew otherwise. On two occasions in 1992, after trying in vain all through one week, she drove the 3½ hours to make the final arrangements for those camps.

Just as she arrived at the Camp, Karen (my then partner took a phone call from an irate man who wanted information about an 'over forties singles' weekend we were trying to set up. This caller was quite abusive. He couldn't understand why we were advertising a business but never answered the phone. Karen burst into tears. She had reached the end of her tolerance, and nothing I could say was any help. When Sister Burke appeared in the office, I decided absence was the better part of valour and removed myself, leaving the two women together. Much later, Sister Burke came out and told me she thought it probably best for both of us if Karen were to leave Cape Bridgewater. I felt numb. It was all happening again.

But it wasn't the same as it had been with Faye. Karen and I sat and talked. True, we would separate, but I assured her that she would lose nothing because of her generosity to me and that I would do whatever was necessary to buy her out. We were both relieved at that. Karen rented a house in Portland, and we remained good friends, though, without her day-to-day assistance at the Camp, which had given me space to travel around, I had to drop my promotional tours.

Twelve months later, in March of 1993, Sister Karen Donnellon, also from Loreto College, tried to make contact via the Portland Ericsson telephone exchange to arrange an annual camp. Sister Donnellon later wrote:

“During a one week period in March of this year I attempted to contact Mr Alan Smith at Bridgewater Camp. In that time I tried many times to phone through.

Each time I dialled I was met with a line that was blank. Even after several re-dials there was no response. I then began to vary the times of calling but it made no difference.” File 231-B → AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233

Some years later, I sent Sister Burke an early draft of my manuscript, Absent Justice My Story‘, concerning my valiant attempt to run a telephone-dependent business without a dependent phone service. Sister Burke wrote back,

“Only I know from personal experience that your story is true, otherwise I would find it difficult to believe. I was amazed and impressed with the thorough, detailed work you have done in your efforts to find justice” File 231-A → AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233

Of course, Sister Maureen Burke and Sister Karen Donnellon persisted with their continuing battle to find a way to get a proper telephone connection for the holiday camp, partly because it was a low-cost holiday for all concerned but also because these wonderful women were well aware that my business was continuing to exist, albeit ‘by the skin of its teeth, even though Telstra’s automated voice messages kept on telling prospective customers that the business did not exist or, alternatively the callers simply reached a dreaded silence that appeared to indicate that the number they had called was attached to a ‘dead’ line. Either way, I lost the business that may have followed if only the callers could have successfully connected to my office via this dreaded Ericsson AXE telephone exchange.

A letter dated 6 April 1993, from Cathy Lindsey, Coordinator of the Haddon & District Community House Ballarat (Victoria) to the Editor of Melbourne’s Herald-Sun newspaper, read:

“I am writing in reference to your article in last Friday’s Herald-Sun (2nd April 1993) about phone difficulties experienced by businesses.

I wish to confirm that I have had problems trying to contact Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp over the past 2 years.

I also experienced problems while trying to organise our family camp for September this year. On numerous occasions I have rung from both this business number 053 424 675 and also my home number and received no response – a dead line.

I rang around the end of February (1993) and twice was subjected to a piercing noise similar to a fax. I reported this incident to Telstra who got the same noise when testing.” Evidence File 10 B

During this same period, 1992 and 1993, Cathy Lindsey, a professional associate of mine Cathy, signed a Statutory Declaration, dated 20 May 1994, explaining several sinister happenings when she attempted to collect mail on my behalf from the Ballarat Courier Newspaper office (File 22 Exhibit 1 to 47). This declaration leaves questions unanswered about who collected my mail and how they knew there was mail to be collected from the Ballarat Courier mail office. On both occasions, when a third person collected this mail, I telephoned Cathy, informing her that the Ballarat Courier had notified me that mail was waiting to be picked up.

On pages 12 and 13 of the transcript from the AFP inquiry into my allegations that Telstra unlawfully intercepted my telephone conversations, the AFP state at Q59 Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1:-

“And that, I mean that relates directly to the monitoring of your service where, where it would indicate that monitoring was taking place without your consent?” File 23-A Exhibit 1 to 47

I also provided the AFP Telstra documents showing that Telstra was worried about my telephone complaint evidence. If it ever reached an Australian court, I had a 50% chance of proving that Telstra had systemic phone problems in their network. In simple terms, Telstra was operating outside of its license to operate a telephone service, charging its customers for a service not provided.

21st April 1993: Telstra internal email FOI folio C04094 from Greg Newbold to numerous Telstra executives and discussing “COT cases latest”, states:-

“Don, thank you for your swift and eloquent reply. I disagree with raising the issue of the courts. That carries an implied threat not only to COT cases but to all customers that they’ll end up as lawyer fodder. Certainly that can be a message to give face to face with customers and to hold in reserve if the complaints remain vexacious .” GS File 75 Exhibit 1 to 88

These Telstra executives forgot that Telstra was a publicly owned corporation. Therefore, those executives were responsible for ensuring the integrity of Telstra's working conditions, something Telstra has never even understood. Bribery and corruption, including misleading and deceptive conduct, destroyed the Australian economy while the powerful bureaucrats attempted to fight this fire with the talk of change. This bribery and corruption plagued the COT cases’ government-endorsed arbitrations.

Children's lives could be at risk

Comments made from the Herald Sun newspaper dated 30 August 1993, confirm just how damaging some of these newspaper articles were to my already ailing business with statements like:

“The Royal Children’s Hospital has told a holiday camp operators in Portland that it cannot send chronically ill children there because of Telecom’s poor phone service. The hospital has banned trips after fears that the children’s lives could be at risk in a medical emergency if the telephone service to the Portland camp continued to malfunction”.

The centre’s stand follows letters from schools, community groups, companies and individuals who have complained about the phone service at Portland’s Cape Bridgewater Holiday camp.”

Youths from the Royal Children’s Centre for Adolescent Health, who were suffering from “chronic illnesses”, visited the camp earlier this year.

Group leader Ms Louise Rolls said in a letter to the camp the faulty phones had endangered lives and the hospital would not return to the camp unless the phone service could be guaranteed” Arbitrator File No/90

After the Melbourne Children's Hospital recorded a near-death experience with me having to rush a sick child with cancer to the Portland Hospital 18 kilometres away from my holiday camp, Telstra finally decided to take my telephone faults seriously. None of the 35 children (all with cancer-related illnesses) had mobile phones, or the six or so nurses and carers. Mobile telephones could not operate successfully in Cape Bridgewater until 2004, eleven years after this event. My coin-operated gold phone was also plagued with phone problems, and it took several tries to ring out of the holiday camp. An ambulance arrived once we could ring through to the Hospital.

After five years, it took almost tragedy for Telstra to send someone with real technical experience to my business. Telstra's visit happened on 3 June 1993, six weeks after the Children's Hospital vowed never to revisit my camp until I could prove it was telephone fault-free. No hospital where convalescent is a good revenue spinner has ever visited my business, even after I sold it in December 2001.

It was another fiasco that lasted until August 2009, when not-so-new owners of my business were walked off the holiday camp premises as bankrupts (Refer to Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story and Chapter 5 Immoral - Hypocritical Conduct

Thus, I continued my quest to secure a functional phone service for the property, which was essential for the success of my enterprise. Throughout this challenging journey, I received compensation for business losses and assurances that the issues would be rectified—assurances that have yet to materialize. I sold the business in December 2001, yet subsequent owners faced analogous challenges. I was not alone in this struggle; other independent business operators similarly affected by inadequate telecommunications joined me, collectively referring to ourselves as the Casualties of Telecom or the COT cases.

Our objective was not only to have Telstra acknowledge our grievances but also to prompt the company to rectify the ongoing issues and provide appropriate compensation for our losses. Is it unreasonable to request a reliable phone service?

Initially, we sought a comprehensive Senate investigation into Telecom to illuminate the gravity of our concerns. Instead, we were presented with an arbitration process as a purported resolution—a path we believed could facilitate a satisfactory conclusion. Eager for resolution, we accepted this alternative, confident that the technical difficulties impeding our phone service would finally be addressed. Unfortunately, this optimism proved misplaced.

Doubts regarding the integrity of the arbitration process emerged almost immediately. We had been assured that essential documents from Telecom would be made available during arbitration to support our case. However, these documents were never provided, leaving us without the critical evidence to substantiate our claims. Our apprehensions deepened when we discovered that our fax lines were unlawfully monitored during the arbitration. Consequently, with the overwhelming influence of the Government against us, we faced an unfavourable outcome. Further compounding our issues, we were misled into signing a confidentiality clause, which hindered our ability to advocate for ourselves.

In the follwing letter (in the image below) dated November 10, 1993, Telstra's Doug Campbell informed Telstra Ian Campbell (not relative) about a significant development. Ian Campbell had previously agreed with the government to arbitrate the COT matters based on the Coopers & Lybrand report. The draft findings in this report acknowledged the validity of the COT Case claims. However, it became evident that Telstra was pressuring Coopers & Lybrand to alter their conclusions concerning Telstra's unethical conduct towards the COT. This is indicated in the following letter

- "...I believe that it should be pointed out to Coopers and Lybrand that unless this report is withdrawn and revised, their future in relation to Telecom may be irreparably damaged."

This confidentiality agreement prevented us from disclosing the harmful actions taken against our businesses by Telstra, the arbitrator, and the independent arbitration consultants. These consultants were allegedly exonerated from all negligent acts they systematically committed under the direction of the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman. It appears the Ombudsman was sharing privileged government information regarding individual COT cases and our welfare, which ultimately assisted Telstra in undermining our arbitration claims, as the following documents demonstrate (TIO Evidence File No 3-A - Refer also to Chapter 1- Prior to Arbitration).

You will learn from the documents on this website that while the COT Cases were being forced into arbitration, the best way forward in getting Telstra to address our telephone issues was suggested. It was communicated to the COT Cases and the media that the arbitrator could not issue a final award or finding regarding each of the arbitration claims until Telstra resolved all ongoing problems related to the COT Cases, which would be investigated independently by the arbitration unit. This might be the best option for all parties involved at that time.

No one would have expected that the former President of the Law Council, Dr Gordon Hughes, once appointed as the arbitrator, would covertly allow the alteration of Clause 24, which exonerated the arbitration legal counsel. Clauses 25 and 26 were removed from the agreed arbitration agreement, which had already been signed on April 8, 1994, by one of the COT Cases, Maureen Gillan. After this agreement was faxed to various government ministers and the COT Cases' lawyers on April 19, 1994, the remaining three claimants—myself, Ann Garms, and Graham Schorer—were forced to agree to sign this agreement being told if we did not then we would be left with having to take Telstra to court. We did not have the revenue to take the government-owned Telstra to court. We reluctantly signed.

After we signed ours, the arbitrator allowed the reinstatement of Clauses 25 and 26 (Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct) in all the other arbitration agreements. This change enabled the twelve remaining COT claimants to sue the arbitration consultants for up to $250,000, the exact liability cap removed from Ann Garms, Graham Schorer, and my arbitration agreement.

It is profoundly concerning that Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator presiding over these complex cases, continues to rely on the revised Confidentiality Agreement. This document, initially intended to protect sensitive information, has now been repurposed by Dr. Hughes to safeguard himself and his consulting team, who endorsed these detrimental modifications. Such actions raise significant and troubling questions regarding the integrity of the arbitration process and all parties' accountability. These critical issues must be thoroughly examined and addressed to restore confidence in the system's integrity.

I seek to understand the potential reactions of the partners and associates at Davies Collison Cave should Dr. Gordon Hughes, the current Principal Partner, disclose that he authorized substantial alterations to the arbitration agreement. Additionally, he convened a clandestine meeting to discuss these changes without informing the claimants. This meeting was attended exclusively by Telstra's arbitration defence legal team members, their senior arbitration advisor, the attorney representing the arbitrator, the arbitration administrator, and the administrator's legal counsel. Notably, the claimants adversely affected by these modifications were neither notified of the meeting nor granted access to the minutes documenting the discussion. Such exclusions further compound the opacity surrounding the decision-making process and exacerbate concerns about fairness and transparency in the arbitration proceedings.

This compelling narrative clearly illustrates that the collusion and fraudulent activities continued unabated. While the arbitrator prioritizes the interests of the arbitration consultants at the expense of the COT, further instances of fraud and the misappropriation of funds linked to Telstra are being uncovered both within Telstra and at the government level. It is critical to note that before Dr Gordon Hughes was appointed an arbitrator, the COT Cases were not informed of his Sydney partnership's representation of Telstra technicians—many of whom, alongside other technicians across Australia, were under investigation regarding the serious issues outlined in the Senate Hansard.

I must take the reader forward fourteen years to the following letter dated 30 July 2009. According to this letter dated 30 July 2009, from Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) and ex-client of the arbitrator Dr Hughes (see Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest) wrote to Paul Crowley, CEO Institute of Arbitrators Mediators Australia (IAMA), attaching a statutory declaration (see Burying The Evidence File 13-H and a copy of a previous letter dated 4 August 1998 from Mr Schorer to me, detailing a phone conversation Mr Schorer had with the arbitrator (during the arbitrations in 1994) regarding lost Telstra COT related faxes. During that conversation, the arbitrator explained, in some detail, that:

"Hunt & Hunt (The company's) Australian Head Office was located in Sydney, and (the company) is a member of an international association of law firms. Due to overseas time zone differences, at close of business, Melbourne's incoming facsimiles are night switched to automatically divert to Hunt & Hunt Sydney office where someone is always on duty. There are occasions on the opening of the Melbourne office, the person responsible for cancelling the night switching of incoming faxes from the Melbourne office to the Sydney Office, has failed to cancel the automatic diversion of incoming facsimiles." Burying The Evidence File 13-H.

Dr. Hughes’s failure to disclose the faxing issues to the Australian Federal Police during my arbitration is deeply concerning. The AFP was investigating the interception of my faxes to the arbitrator's office. Yet, this crucial matter was a significant aspect of my claim that Dr Hughes chose not to address in his award or mention in any of his findings. The loss of essential arbitration documents throughout the COT Cases is a serious indictment of the process.

The loss of essential arbitration documents throughout the COT cases is a significant indictment of the arbitration process. During my arbitration, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) conducted a second interview at my business on September 26, 1994, where they asked me 93 critical questions about their investigation into the bugging issues (refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1). Their concerns centered on my privacy and the serious threats I received from Paul Rumble, Telstra's arbitration liaison officer. I want to emphasize that Dr. Gordon Hughes blatantly disregarded the arbitration agreement by unlawfully providing Rumble with my arbitration-related documents. Telstra was contractually allowed only one month to review my claim, yet Dr Hughes shamefully extended their access to an astonishing seven months. This breach of protocol is unacceptable.

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my illegal phone/fax interception allegations. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

These links, from pages 5163 to 5169, → SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia reveals that Telstra employees were siphoning off millions of dollars from Telstra shareholders, which was the government and the people of Australia who made up the government. In simple terms, the Casualties of Telstra had a moral duty. Many individuals made threats against the COT cases because our persistent efforts to secure fully functional phone systems were about to uncover other unethical practices at Telstra, including those at the management level. Shockingly, the Telstra CEO and board were aware that millions of dollars were being unlawfully extracted from government funds. Reports have even suggested that the figures run into the billions.

On 21 March 1997, twenty-two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to my arbitration), wrote to Telstra's Ted Benjamin (see File 596 AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) asking:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin (clinical psychologist’s).

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?"

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehill's, signed the witness statement without the psychologist's signature shows how much power Telstra lawyers have over the legal system of arbitration in Australia.

Systemic billing issues at Telstra ultimately proved financially advantageous for the company. In my particular case, the board of Telstra authorized the arbitration defence unit to submit nine false witness statements, which were sworn under oath on December 12, 1994. These statements misled the arbitrator by asserting that there were no known systemic billing faults related to the 008/800 numbers that affected my business, neither at that time nor currently.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Frank Blount, the CEO of Telstra, had previously contacted me in March 1994 at my holiday camp to discuss these systemic billing problems. Despite this prior engagement, he permitted submitting the aforementioned false witness statements. In 2000, following a substantial payout from the Australian government for his seven years of service, Mr Blount co-authored a book entitled "Managing in Australia" https://www.qbd.com.au › managing-in-australia › fran, which can still be purchased online. It is significant that, on pages 132 and 133 of this publication, the co-author wrote:

- "Blount was shocked, but his anxiety level continued to rise when he discovered this wasn’t an isolated problem. The picture that emerged made it crystal clear that performance was sub-standard.” (File 122-i - CAV Exhibit 92 to 127).

Helen Handbury, the sister of Rupert Murdoch, stayed at my holiday camp on two occasions. She slept in my converted Presbyterian church from the 1870s, which accommodated twelve people. After reading the first draft of absentjustice.com, Mrs. Handbury mentioned that she would ask Rupert to publish it. I have explained in the image why I never personally pursued Rupert Murdoch, as suggested by Mr. Handbury.

On January 27, 1999, I took a significant step by sharing my first manuscript draft, absentjustice.com. This document, which detailed my experiences and frustrations, caught the attention of Helen Handbury, the sister of media mogul Rupert Murdoch.

As Helen read through the pages, she became visibly emotional, nearly bursting into tears. Helen could relate deeply to the challenges I described, particularly the frustrating telephone issues she had faced while attempting to reach a holiday camp she had stayed at on two separate occasions. The manuscript also caught the eye of Senator Kim Carr. After he reviewed it, he expressed his thoughts in writing, indicating a serious engagement with the content and the issues I highlighted. His response suggested that the themes in my manuscript resonated with him as well, emphasizing the widespread impact of the injustices I attempted to address.

Infringe upon the civil liberties.

Most Disturbing And Unacceptable

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

During her second visit, Helen Haddbury animatedly shared her plans to enlist her brother Rupert, a prominent media mogul, to help bring my story to the public's attention. As she spoke, I felt a knot tightening in my stomach; I hesitated to reveal that Rupert was already acutely aware of the grave inadequacies plaguing Telstra’s infrastructure. After all, he had successfully pursued a jaw-dropping $400 million claim against the telecommunications behemoth, exposing its failures. This stark contrast in our positions underscored the vast chasm in power and resources—Rupert’s influence was monumental. At the same time, we, the COT cases, felt like mere whispers in the chaotic din of corporate negligence as the Rupert Murdoch -Telstra Scandal - Helen Handbury) pages show.

I'm grateful for her Helens comments.

When Helen Handbury, Rupert Murdoch's sister, visited my holiday camp a second time after reading my manuscript at absentjustice.com, she promised to provide my evidence supporting this website to her brother Rupert. She believed he would be appalled by Telstra's disregard for justice. I hesitated to inform Helen that Rupert Murdoch knew about Telstra's unethical practices. These illegal activities cost every Australian citizen millions of dollars in lost revenue. This revenue should have rightfully gone to the government and its citizens. This information is well documented in SENATE Hansard; therefore, Rupert Murdoch would have been aware that through Telstra's unethical practices, News Corp and Foxtel were compensated by Telstra for not meeting their cable rollout commitment time. This is quoted from point 10, pages 5164 and 5165→ SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia

Telstra’s CEO and Board have known about the scam since 1992. They have had the time and opportunity to change the policy and reduce the cost of labour so that cable roll-out commitments could be met and Telstra would be in good shape for the imminent share issue. Instead, they have done nothing but deceive their Minister, their appointed auditors and the owners of their stock— the Australian taxpayers. The result of their refusal to address the TA issue is that high labour costs were maintained and Telstra failed to meet its cable roll-out commitment to Foxtel. This will cost Telstra directly at least $400 million in compensation to News Corp and/or Foxtel and further major losses will be incurred when Telstra’s stock is issued at a significantly lower price than would have been the case if Telstra had acted responsibly.

It is imperative to underscore the $400 million compensation deal negotiated between Telstra, Rupert Murdoch, and Fox. This arrangement stipulated that Telstra would owe $400 million if it failed to deliver the committed telecommunications services by the deadline.

My primary concern does not pertain to the compensation that Telstra is obligated to provide in the event of a missed deadline in delivering all promised services to FOX. In sixteen COT cases, all Australian citizens were promised similar commitments by Telstra on the condition that they financed their own arbitrations to resolve ongoing issues. Unfortunately, the telephone problems experienced by the COT Cases were not addressed in these costly arbitration proceedings. In certain instances, these individuals continue to endure challenges due to the unfulfilled commitments made by both Telstra and the arbitrator.

Telstra's extensive involvement in numerous sectors made even the most straightforward issues complex. Questions arose about who authorized the purchase of vehicles in each state, where office supplies were obtained, which technologies were deployed, and even the origins of their copper wire. The situation was grim, as everyday employees engaged in dubious practices, such as invoicing for work that was never performed and booking motel accommodations for country visits that they ultimately did not utilize. As highlighted in the Senate Hansard records, millions of dollars were misappropriated in this chaotic environment.

When the COT Cases began to question the persistent problems in their copper line customer access network—issues that had lingered for years following their initial complaints—Telstra's board found itself in a precarious position. High-ranking legal experts and partners from at least 47 of Australia’s most prominent legal firms, all on Telstra's payroll, were poised to lose substantial amounts of money as the Senate initiated its investigations into the company's practices.

During this critical period, the COT Cases faced fierce backlash—not due to any wrongdoing, but because their earnest inquiries into Telstra's inadequate service threatened to unravel a web of corruption. The COT cases were met with blatant disregard and treated as nuisances rather than serious complaints. If you continue reading this gripping true narrative about the COT Case, you will uncover the shocking depths of neglect and deception they encountered.

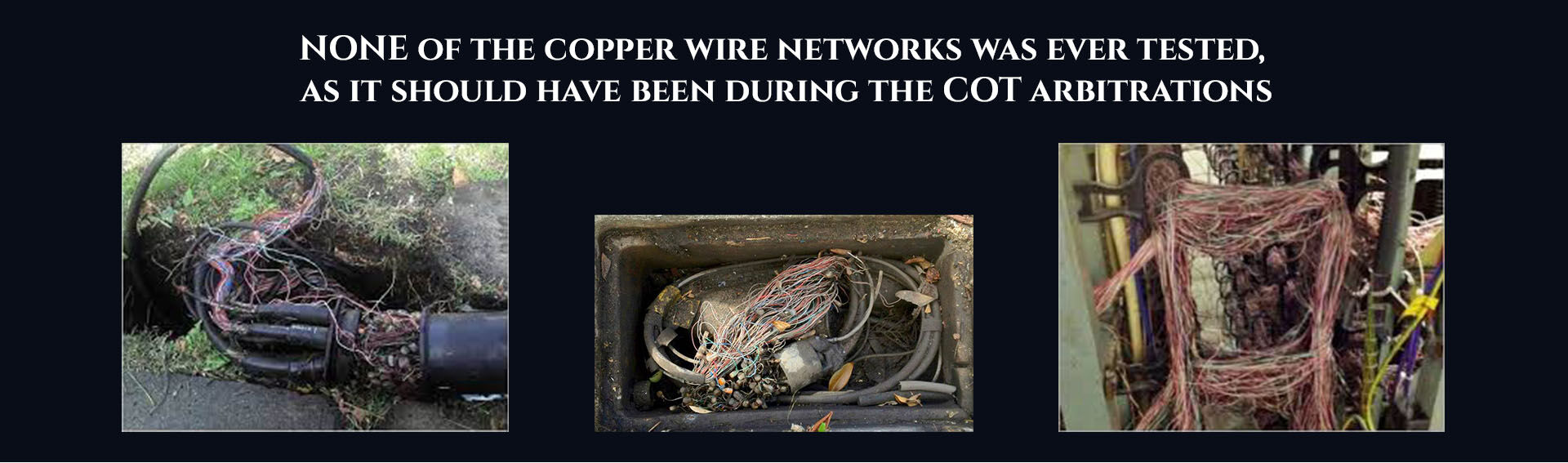

The persistent troubles with telephone and fax services, which the arbitrator neglected to address before delivering his findings, are a significant contributing factor to the ongoing decline of Australia’s telecommunications infrastructure. Detailed reports from AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) make clear that the arbitrator was mandated to ensure that Telstra's arbitration service verification testing for each Customer-Owned Telecommunications (COT) case adhered to strict government specifications. Shockingly, the arbitrator permitted Telstra to carry out these critical arbitration tests without the oversight of government-appointed independent technical consultants, who, had they been appointed, would have uncovered how degraded the Ericsson equipment was.

The arbitration technical consultants, who were appointed to evaluate the onsite telephone equipment of the COT Cases, did not test any Telstra-installed Ericsson telephone equipment at the COT Cases premises or at the exchanges that connected to them. This was a significant oversight, considering that appointing these technical consultants was to ensure a thorough assessment. Both the Shadow Minister of Communications, Richard Alston, and the Minister of Communications, Michael Lee MP, who were in office at the time of the arbitrations, agreed that it was far more essential to have the arbitration consultants present when Telstra conducted tests at the COT Cases premises than to merely review Telstra's working notes related to their registered complaints.

When the COT Cases exposed the Ericsson AXE call loss rate to AUSTEL (the then government communications regulator), AUSTEL (now ACMA) instigated an investigation into these AXE exchange faults and uncovered some 120,000 COT-type complaints were being experienced around Australia. Exhibit Introduction File No/8-A to 8-C) shows AUSTEL’s Chairman Robin Davey received a letter from Telstra’s Group General Manager, suggesting he alter that finding:

For example, at point 4 on page 3, Telstra writes:

“The Report, when commenting on the number of customers with Cot-type problems, refers to a research study undertaken by Telecom at Austel’s request. The Report extrapolates from those results and infers that the number of customers so affected could be as high as 120,000.

However, at point 2 on page 1 of Telstra’s letter 9 April 1994, Telstra writes:

“In relation to point 4, you have agreed to withdraw the reference in the Report to the potential existence of 120,000 COT-type customers and replace it with a reference to the potential existence of “some hundreds” of COT-type customers”.

The fact that on this occasion, on 9 April 1994, Telstra (the defendants) were able to pressure the Government Regulator to change their original findings in the formal April 1994 AUSTEL COT Case report is alarming, to say the least. Worse, when AUSTEL released it into the public domain, the report states that AUSTEL only uncovered 50 or more COT-type complaints. (Refer to Open Letter File No/11) and Falsification Report File No/8).

50 COT-type customer Ericsson AXE complaints compared to 120,000 COT-type customer AXE complaints is one hell of a lie told by the government to its citizens who voted it into power → Chapter 1 - Can We Fix The CAN

Government Corruption

Threats made during my arbitration

On July 4, 1994, amidst the complexities of my arbitration proceedings, I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra's arbitration defence team representative. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred an entire month before the arbitrator was legally obligated to share such information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. I poured considerable effort into crafting this detailed letter, carefully choosing every word. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no plans to submit any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardize my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could impact the arbitrator's decisions regarding my case.

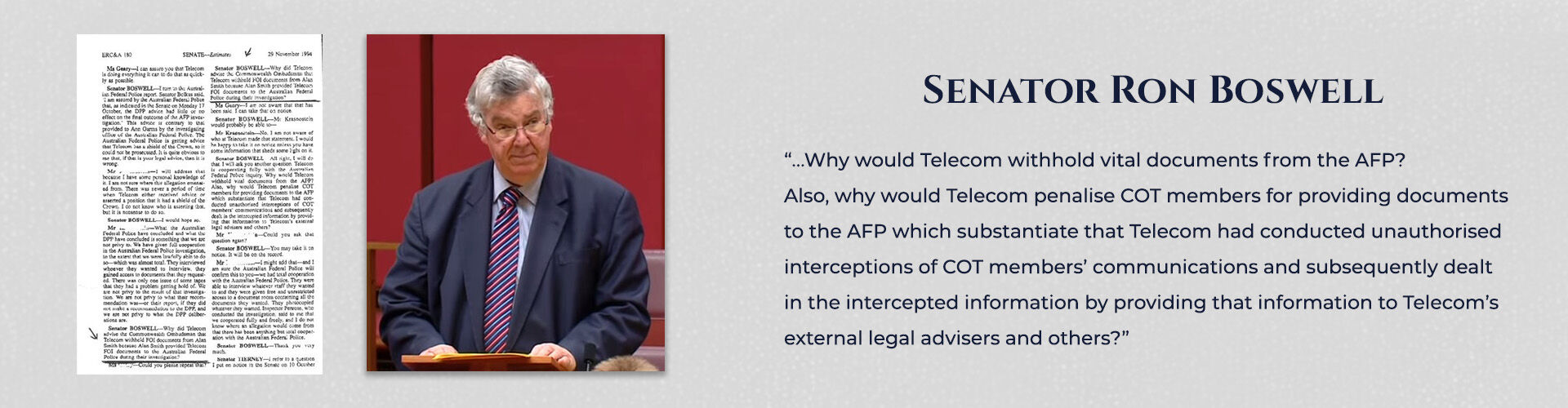

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on September 26, 1994. During this visit, they began to pose probing questions regarding my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result of this situation, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the Senate. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this - no one in the TIO office or government has ever investigated the disastrous impact the withholding of documents had had on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen, who had assisted the AFP in their investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations, was so severely disadvantaged during a civil arbitration.

Pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts provide a comprehensive account establishing Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

Firstly, Mr. Rumble actively obstructed the provision of essential arbitration discovery documents, which the government was legally obligated to provide under the Freedom of Information Act. This obligation was contingent on my signing an agreement to participate in a government-endorsed arbitration process. By imposing this condition, Mr Rumble undermined a legally established protocol, effectively manipulating the process for his benefit and jeopardizing my legal rights.

Secondly, I uncovered that Mr. Rumble had a substantial influence over the arbitrator, resulting in the unauthorized early release of my arbitration interim claim materials. This premature revelation directly conflicted with the timeline stipulated in the arbitration agreement that Telstra and I had formally signed. Specifically, Telstra gained access to my interim claim document five months earlier than what was permitted under the agreed-upon terms. This breach of protocol violated the integrity of the arbitration process and provided Telstra with an unfair advantage in their response to my claims.

According to the rules governing our arbitration process, Telstra was allocated one month to respond to my claim once it had been submitted in writing as my final claim. Furthermore, the arbitrator was only authorized to release my final claim to Telstra once it was officially confirmed to be complete. The five-month delay in submitting my claim in November 1994 was primarily attributable to Mr. Rumble's deliberate withholding of critical technical information.

In my case, as Telstra's Falsified SVT Report shows, Telstra’s representative, Peter Gamble, attempted to conduct the essential Service Verification Testing (SVT) process. Unfortunately, he had to halt the testing due to unforeseen equipment malfunctions. When AUSTEL questioned how he planned to rectify this inadequate testing at my business, Mr Gamble refused to proceed with any further testing. Instead, he submitted a statutory declaration under oath to the arbitrator, claiming that his SVT process had fully complied with AUSTEL’s requirements. This assertion was far from the truth.

More Threats, this time to the other Alan Smith

Two Alan Smiths (not related) living in Cape Bridgewater.

No one investigated whether another person named Alan Smith, who lived in the Discovery Bay area of Cape Bridgewater, received some of my arbitration mail. Both the arbitrator and the administrator of my arbitration were informed that road mail sent by Australia Post had not arrived at my premises during my arbitration from 1994 to 1995.

Additionally, the new owners of my business lost legally prepared documents related to Telstra when they attempted to send mail to the Melbourne Magistrates Court. I had prepared these documents in a determined effort to prevent them from being declared bankrupt due to ongoing telephone issues. They were sent from the Portland Post Office but did not arrive (Refer to Chapter 5, Immoral—Hypocritical Conduct).

Stop these people at all costs.

This is the same Peter Gamble who, on 24 June 1997 see:- pages 36 to 38 Senate - Parliament of Australia was named by an ex-Telstra employee turned - Whistle-blower, Lindsay White, that, while he was assessing the relevance of the technical information which the COT claimants had requested under FOI he advised the Committee that:

Mr White - "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-"

From Mr White's statement, it is clear that he identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra had singled out to be ‘stopped at all costs’ from proving their against Telstra’.

Peter Gamble's unethical behaviour is significant, but it is also crucial to highlight that David Read from Lane Telecommunications chose not to oversee Gamble’s tests on April 6, 1995. As the technical consultant for the independent arbitrator, Read was responsible for evaluating the COT Cases, which alleged that faulty Ericsson telephone equipment was the source of ongoing complaints from various businesses.

Furthermore, Lane Telecommunications was acquired by Ericsson during the COT arbitration proceedings. This acquisition had profound implications, as it transferred all investigative materials collected by Lane against Ericsson of Sweden—gathered over approximately eight COT arbitrations—into Ericsson's possession. This situation raises significant ethical concerns about the investigation's impartiality, considering that the entity under scrutiny now controls the evidence against it.

Such circumstances challenge Australia’s stated commitment to the rule of law and suggest that it may be one of the few Western nations that allows a principal witness to be financially influenced by those being investigated (Refer to Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden)

“...Eleven years after their first complaints to Telstra, where are they now? They are acknowledged as the motivators of Telecom’s customer complaint reforms. … But, as individuals, they have been beaten both emotionally and financially through an 11-year battle with Telstra"

“Then followed the Federal Police investigation into Telecom’s monitoring of COT case services. The Federal Police also found there was a prima facie case to institute proceedings against Telecom but the DPP (Director of Public Prosecutions), in a terse advice, recommended against proceeding".

“Once again, the only relief COT members received was to become the catalyst for Telecom to introduce a revised privacy and protection policy. Despite the strong evidence against Telecom, they still received no justice at all".

“These COT members have been forced to go to the Commonwealth Ombudsman to force Telecom to comply with the law. Not only were they being denied all necessary documents to mount their case against Telecom, causing much delay, but they were denied access to documents that could have influenced them when negotiating the arbitration rules, and even whether to enter arbitration at all. …

"This is an arbitration process not only far exceeding the four-month period, but one which has become so legalistic that it has forced members to borrow hundreds of thousands just to take part in it. It has become a process far beyond the one represented when they agreed to enter into it, and one which professionals involved in the arbitration agree can never deliver as intended and never give them justice."

"I regard it as a grave matter that a government instrumentality like Telstra can give assurances to Senate leaders that it will fast track a process and then turn it into an expensive legalistic process making a farce of the promise given to COT members and the unducement to go into arbitration. “Telecom has treated the Parliament with contempt. No government monopoly should be allowed to trample over the rights of individual Australians, such as has happened here.” (See Senate Hansard Evidence File No-1)

“COT Case Strategy”

As shown on page 5169 in Australia's Government SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia Telstra's lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page devised a legal paper titled “COT Case Strategy” (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C) instructing their client Telstra (naming me and three other businesses) on how Telstra could conceal technical information from us under the guise of Legal Professional Privilege even though the information was not privileged.

This COT Case Strategy was to be used against me, my named business, and the three other COT case members, Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan and Graham Schorer, and their three named businesses. Simply put, we and our four businesses were targeted even before our arbitrations commenced.

It is paramount that the visitor reading absentjustice.com understands the significance of page 5169 at points 29, 30, and 31 SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia, which note:

29. Whether Telstra was active behind the scenes in preventing a proper investigation by the police is not known. What is known is that, at the time, Telstra had representatives of two law firms on its Board—Mr Peter Redlich, a Senior Partner in Holding Redlich, who had been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991 and Ms Elizabeth Nosworthy, a partner in Freehill Hollingdale & Page who had also been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991.

One of the notes to and forming part of Telstra’s financial statements for the 1993- 94 financial year indicates that during the year, the two law firms supplied legal advice to Telstra, totalling $2.7 million, an increase of almost 100 per cent over the previous year. Part of the advice from Freehill Hollingdale & Page was a strategy for "managing" the "Casualties of Telecom" (COT) cases.

30. The Freehill Hollingdale & Page strategy was set out in an issues paper of 11 pages, under cover of a letter dated 10 September 1993 to a Telstra Corporate Solicitor, Mr Ian Row from FH&P lawyer, Ms Denise McBurnie (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C). The letter, headed "COT case strategy" and marked "Confidential," stated:

- "As requested I now attach the issues paper which we have prepared in relation to Telecom’s management of ‘COT’ cases and customer complaints of that kind. The paper has been prepared by us together with input from Duesburys, drawing on our experience with a number of ‘COT’ cases. . . ."

31. The lawyer’s strategy was set out under four heads: "Profile of a ‘COT’ case" (based on the particulars of four businesses and their principals, named in the paper); "Problems and difficulties with ‘COT’ cases"; "Recommendations for the management of ‘COT’ cases; and "Referral of ‘COT’ cases to independent advisors and experts". The strategy was in essence that no-one should make any admissions and, lawyers should be involved in any dispute that may arise, from beginning to end. "There are numerous advantages to involving independent legal advisers and other experts at an early stage of a claim," wrote Ms McBride . Eleven purported advantages were listed.

Back then, Mr Redlich was, in most people's eyes, one of the finest lawyers in Australia at that time. He was also a stalwart within the Labor Party, a one-time friend of two Australian Prime Ministers (Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke) and a long-time friend of Mark Dreyfus, Australia's current 2025 Attorney-General in 2024, so who would be the slightest bit interested in listening to my perspective in comparison to someone so highly qualified and with such vital friends?

And remember, the COT strategy was designed by Freehill Hollingdale & Page when Elizabeth Holsworthy (a partner at Freehill's) was also a member of the Telstra Board, along with Mr Redlich. The whole aim of that ‘COT Case Strategy’ was to stop us, the legitimate claimants against Telstra, from having any chance of winning our claims. Do you think my claim would have even the tiniest possibility of being heard under those circumstances?

An investigation conducted by the Senate Committee, which the government appointed to examine five of the twenty-one COT cases as a "litmus test," found significant misconduct by Telstra. This was highlighted by the statements of six senators in the Senate in March 1999:

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Regrettably, because my case had been settled three years earlier, I and several other COT Cases could not take advantage of this investigation's valuable insights or recommendations. Pursuing an appeal of my arbitration decision would have incurred significant financial costs that I could not afford as shown in an injustice for the remaining 16 Australian citizens.

During the investigation by the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group into the alleged fraudulent conduct by Telstra during and after the COT arbitrations, the Scandrett & Associates report was delivered to Senator Ron Boswell on 7 January 1999. This report confirmed that faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations (refer to Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13). Furthermore, one of the two technical consultants who verified the validity of this fax interception report reached out to me via email on 17 December 2014, emphasizing the importance of these findings

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

The evidence within this report Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) also indicated that one of my faxes sent to Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was similarly intercepted, i.e.,

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

The actions taken by Telstra during a government-endorsed arbitration process, as well as during investigations by the Australian Federal Police between 1994 and 1995 and the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group from late 1998 to 2001, are undeniably severe. It is both alarming and unacceptable that Telstra employees have not considered legal repercussions for these actions. This highlights a troubling lack of accountability and transparency, casting doubt on the integrity of the systems meant to protect small businesses and uphold the rule of law.

In March and April 2006, I presented several examples of intercepted documents from the COT arbitrations to the Hon. Senator Helen Coonan, Minister for Communications. One notable example included a document addressed to the Hon. Peter Costello, our former Australian Federal Treasurer. The Senator responded to me on 17 May 2007,

"I have now made both formal and informal representations to Telstra on behalf of the CoTs. However, Telstra’s position remains that this is a matter that is most appropriately dealt with through a Court process. Telstra is not prepared to undertake an alternative means of pursuing this matter. I also appreciate the depth of feeling regarding the matter and suggest you consider whether any court proceedings may be your ultimate option". (File 616-B AS-CAV Exhibits 648-a to 700)

It was unequivocally Senator Helen Coonan’s responsibility, as the Minister for Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, to initiate a thorough and official inquiry into the matter of Telstra's continuous interception of confidential documents that were being sent from my office and my residence, as well as from the offices of several Senators and the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s office. This issue was particularly critical during and following the COT arbitrations, where sensitive information was exchanged.

The gravity of this situation raises critical questions: Why was it considered acceptable for an Australian citizen to be compelled to take legal action against Telstra for unlawfully intercepting documents leaving and arriving at Parliament House in Canberra during a government-endorsed arbitration process? Furthermore, why was Telstra interpreting my faxes to government ministers three years after the conclusion of my arbitration?