Introduction

I never set out to expose a national scandal. All I wanted was a working phone line. But the moment I realised my own telecommunications faults weren’t “isolated incidents” at all, everything changed. I became one of the founding members of a small group of business owners who were experiencing the same failures, denials, and bureaucratic brick walls. Together, we became known as the Casualties of Telstra — COT — a name that would come to symbolise a fight far bigger than any of us expected.

For years, I lived inside a story most Australians would struggle to believe — a story built on government interference, corrupted processes, and a telecommunications corporation whose misconduct reached into homes, businesses, and entire communities. What began as a simple complaint about faulty phone and fax lines slowly unravelled into a labyrinth of systemic injustice, FOI obstruction, and political cover‑ups stretching from Parliament House to the smallest rural exchanges in the country.

The deeper I went, the more I understood that I wasn’t just challenging Telstra. I had stepped into the centre of a true‑crime‑style investigation — one fuelled by falsified engineering reports, doctored test results, and an arbitration system that looked legitimate on paper but operated like a machine designed to fail those it claimed to protect. The COT Cases were promised fairness. Instead, we were fed into a process engineered to shield the powerful and silence the vulnerable.

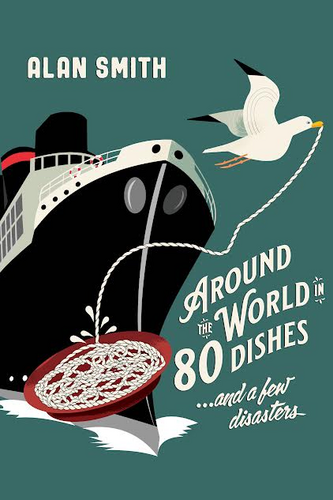

If anyone can relate to this captivating COT story and has doubts about my integrity, I warmly invite you to explore my latest book, available for the modest price of $5.99 AUD on my website: https://www.promoteyourstory.com.au/. Titled "Around The World in 80 Dishes...and a Few Disasters." This book is about the man behind this website, absentjustice.com, which takes you on a journey through my life before the COT issues changed everything.

If anyone can relate to this captivating COT story and has doubts about my integrity, I warmly invite you to explore my latest book, available for the modest price of $5.99 AUD on my website: https://www.promoteyourstory.com.au/. Titled "Around The World in 80 Dishes...and a Few Disasters." This book is about the man behind this website, absentjustice.com, which takes you on a journey through my life before the COT issues changed everything.

Fast forward to 2026, and the Australian Government remains deeply complicit in this web of deceit, choosing to ignore the fraud that poisoned my government‑endorsed arbitration. It forces a hard question: what is driving their silence?

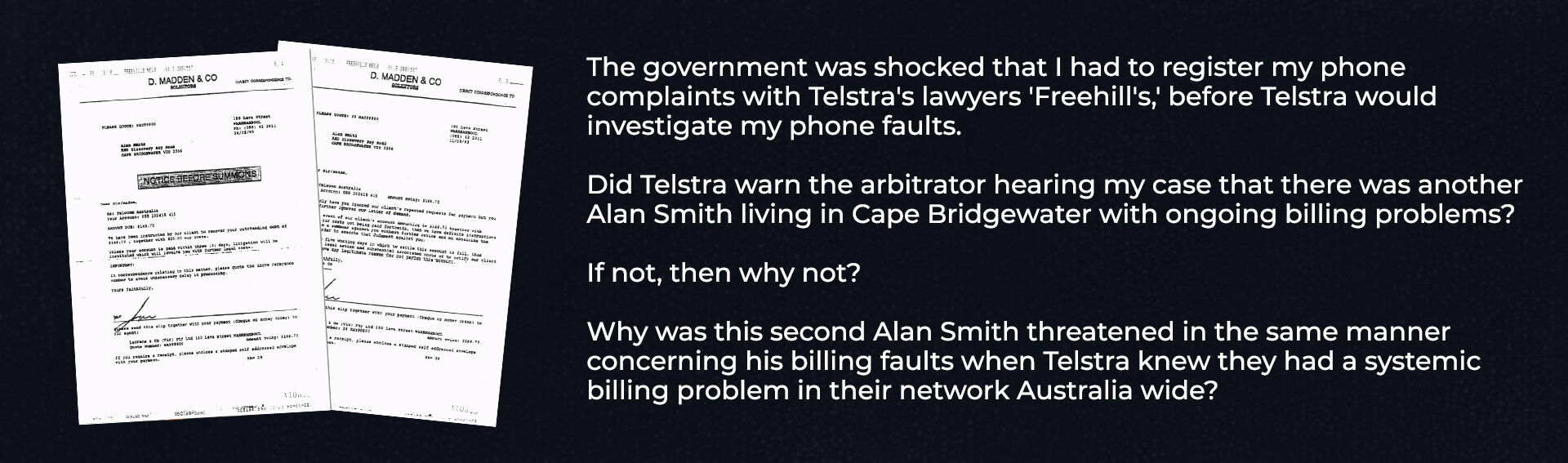

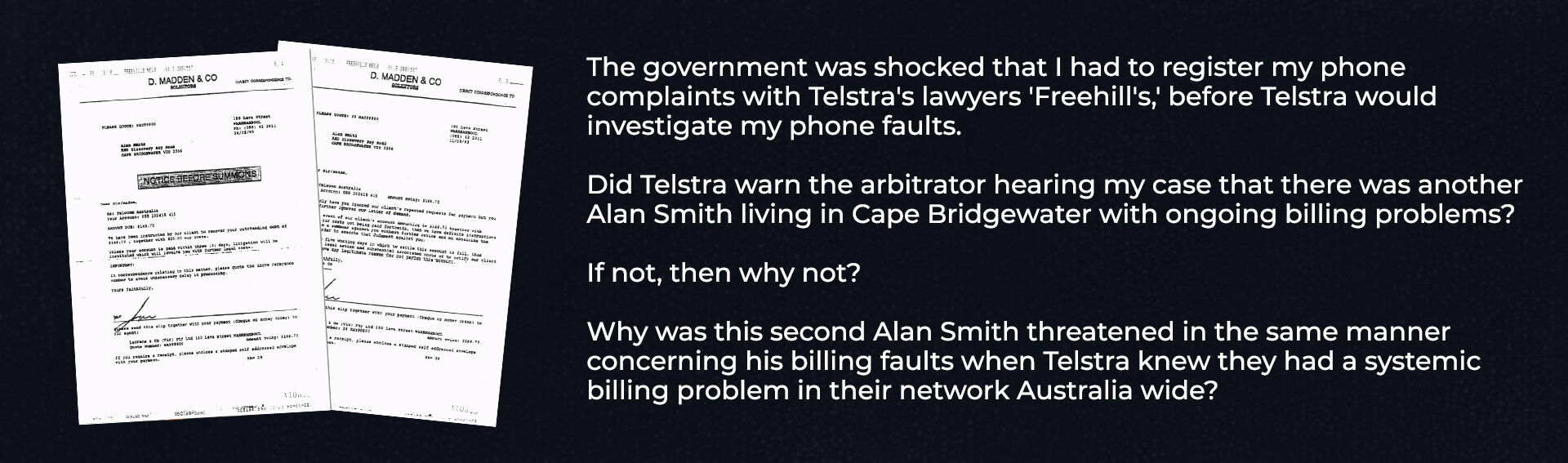

DMR Group Canada Inc. was brought in from Canada during my arbitration to evaluate and assess my technical claim. Paul Howell from DMR Canada International contacted me to inform me that he did not sign off on his report regarding my arbitration because the arbitrator did not provide him with sufficient time to evaluate my ongoing billing problems. If Bell Canada International Inc. had conducted its testing as described in its Cape Bridgewater report, it would have uncovered the systemic billing issues.

Inside Telstra’s own vaults were documents revealing Ericsson AXE exchange faults so widespread they corrupted billing data across the nation. Yet the public was assured the network was sound. Bell Canada International testing was held up as proof of world‑class performance, even though the tests were never conducted as claimed. These falsified results became the foundation of the Telstra arbitration scandal — a scandal that helped pave the way for privatisation while concealing network failures that had crippled small businesses for years.

Two months after my arbitration, after I submitted the same letter and supporting evidence to both the Australian and Canadian Governments, it became evident that the Australian authorities had turned a blind eye to a disturbing reality. The Cape Bridgewater Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) test results, which were clearly flawed, were utilised by Telstra as leverage in their arbitration defence. I raised concerns about three other COT Cases in which Telstra employed similar reprehensible BCI test results to bolster its defence, yet all those claims remain unresolved. It is alarming that the Australian Government has remained silent, while the Canadian Government was the only entity to respond, shedding light on the sinister implications of this entire situation.

When we sought answers through FOI, we encountered obstruction, suppression, and bureaucratic silence. Evidence that should have been released was withheld. Reports that should have been scrutinised were buried. It was a pattern of government cover‑ups, public service misconduct, and institutional betrayal no citizen should ever have to face.

As I pieced together the fragments, I realised I was documenting far more than a telecommunications dispute. I was uncovering corporate misconduct, legal system failures, and a breakdown in government accountability that belonged in the pages of a true‑crime exposé. The story of the COT Cases was never just about faulty lines — it was about hidden scandals, real corruption, and the quiet persistence of whistleblowers determined to expose the truth.

The Australian government allowed the main technical consultant to the arbitration (the witness) to some twelve arbitration claims against Ericsson and Telstra, and the poor service collectively provided to the COT Cases business, to be purchased by Ericsson once Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd had collected all of the Ericsson and Telstra data under a confidentality agreement that has stopped the COT Cases arbitrations from being investigated regardless of the evidence that the process was conducted outside of the endorsement by the government.

No testing was conducted by Bell Canada International through the AXE Ericsson - Telstra telephone exchange at Portland or Cape Bridgewater, which serviced my business. Evidence that these tests are impractical can be found by clicking on the Canadian flag image below.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

The evidence on absentjustice.com is overwhelming:

1. Fax Interception During Arbitration: Evidence of unauthorised fax interception has been documented in detail, as outlined in documents Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13. These records shed light on how sensitive communications were compromised during the arbitration process.

2. Falsified Testing Reports: There is substantial evidence of Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2 including Tampeing with Evidence. This manipulation of evidence raises serious concerns about the integrity of the information presented during arbitration.

3. Withheld Files: Crucial files that could have impacted the arbitration outcome were intentionally withheld until after the proceedings concluded. These documents reveal that the government had already substantiated my claims against Telstra a full 12 years before I was subjected to arbitration (see points 2 and 212 AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings

4. Compromised Arbitration Process: A comprehensive trail of documents exposes how the arbitration process was fundamentally compromised from within. This evidence is detailed in Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct, which discusses fraudulent conduct related to the case.

5. Lack of Control by the Arbitrator: It is evident that the arbitrator had no real control over the arbitration process, as the proceedings were conducted entirely outside the agreed-upon procedures. For a thorough understanding of this issue, refer to page COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D).

What has emerged from the five listed points above and from the thousands of evidence files contained on this website, absentjustice.com, is a true story of Australian government cover-ups — a story that connects every thread, from arbitration injustice to systemic telecommunications failures, from political misconduct to an Australian investigative narrative that has never been fully told.

This is the history of the COT Cases. This is evidence of Telstra’s misconduct in arbitration. This is the proof of FOI withholding. This is the story Australia was never meant to read.

Years after my arbitration concluded, I finally discovered evidence indicating that Bell Canada International Inc. could not have performed their testing as stated in their report. This was due to issues with the Ericsson AXE telephone exchange at Portland and Cape Bridgewater, linked to numerous deficiencies in the Ericsson AXE equipment servicing those exchanges, which BCI claimed were tested.

It became evident that the arbitration consultant, Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd, had taken sensitive information with them when they defected to Ericsson during Ericsson's acquisition of Lane. This move raised significant concerns, as Lane was supposed to conduct an impartial investigation into the very company they were now affiliated with.

The documents I uncovered showed that if I had accessed this information during my arbitration—when I rightfully requested it under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act—or had received it during my ongoing appeal process, which the Canadian Government was morally trying to assist me with, it would have been sufficient to overturn the unjust dismissal of my claims. This information had the potential to expose Telstra's unlawful use of BCI testing and would have significantly strengthened my position in the pending appeal process. The entire situation seems to reflect corruption and a cover-up, leaving me questioning the integrity of those responsible for ensuring fairness in the arbitration process.

The Forced Agreements and the Stripping Away of Legal Protections

Meanwhile, three of the four COT Cases, Ann Garms, Graham Schorer and I, all small business owners, were ruthlessly coerced into signing our arbitration agreement on 21 April 1994, where the $250.000.00 liability clauses 25 and 26 had been removed, which meant we could not sue the technical and financial consultants assisting the arbitrator to the tune of $250,000.00 each. Clause 24 of the same agreement was changed, meaning the arbitration legal counsel could not be sued for negligence for any amount whatsoever.

With us three COT Cases already in finacial dire straits, burdened with exorbitant arbitration fees to be met, and having our ongoing telephone issues investigated under a facade of impartiality, we were sitting ducks.

The remaining goodwill in the arbitration agreement for desperate small business owners was that, if our claims were found valid and the issues jeopardised the very existence of our businesses, Telstra would be compelled to address the ongoing problems before the arbitrator issued a formal binding award. The first of the four claimants, Maureen Gillan, signed her agreement on 8 April 1994. This agreement had initially been endorsed by many Senators and by the attorneys representing the other three claimants.

Six months into the lead-up to our arbitrations, we had not received a single relevant Freedom of Information (FOI) document. The documents we received were heavily redacted and lacked attached schedules that would explain their relevance, rendering it futile to continue our efforts. Despite this, we continued to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in professional technical fees trying to understand the contents of the released documents.

A Fractured Arbitration Process: Sixteen Claims, Three Different Rules

It is important to note that twelve other COT Cases joined our group, and their arbitration proceedings began two months later. In their arbitration agreements, the $250,000.00 liability cap was replaced, although the legal counsel involved was still exonerated of all legal liability.

Additionally, the twelve claimants had written assurances included in their arbitration agreements stating that they would receive relevant documents before arbitration began. In contrast, Telstra had promised to provide our documents only after we signed the four arbitration agreements.

In simpler terms, within three months of conducting the sixteen arbitrations simultaneously, the arbitrator—who I later discovered was not a graded arbitrator until well after the completion of my arbitration, which concluded on 11 May 1995—Dr Gordon Hughes was managing three distinct arbitrations. Each had different clauses attached or removed, which led to a loss of control in the arbitration process, as discussed below.

The critical stipulation mentioned above is that the arbitrator could not issue a formal final award for lost revenue if the problems remained unresolved on the day the findings were delivered. This troubling procedure was clearly outlined in the AUSTEL-prepared COT Cases Report issued in April 1994, which is also a document shrouded in deception and provided to both the arbitrator and the claimants.

The Arbitrator’s Secret Exonerations and the Collapse of Natural Justice

Just as the claims were bound to this grim arbitration process, on 22 March 1994, Dr Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator appointed for this dark undertaking, began to exonerate the arbitration consultants from any negligence allegations from the COT claimants. He cunningly removed Clauses 25 and 26, which had established a $250,000 liability cap—a cap that had been agreed upon by the government and COT Cases lawyers as a protective measure for claimants. This manoeuvre stripped the claimants of any semblance of power against Telstra, an entity with a notorious reputation for winning at any cost, no matter how grotesque their tactics.

In my case, and in that of Ann Garms, who was similarly ensnared, we were forced to accept Dr Hughes’s treacherous decision on 21 April 1994. This allowed the consultants to operate without fear of accountability. This calculated betrayal ensured that none of the ongoing billing problems that plagued my business was ever investigated, a fact corroborated in writing by the government communications regulator in August and again on 16 October 1995 (refer to Absent Justice Part 2 - Chapter 14 - Was it Legal or Illegal?. They shamelessly permitted Telstra to manipulate my arbitration billing documents—covertly and without scruples—five months after the arbitration process had supposedly concluded.

By barring me from this clandestine hearing, the arbitrator and Telstra conspired to deny me my legal right to respond to their underhanded submission on 16 October 1995, as well as to the arbitrator's scurrilous findings on that submission.

I trust that anyone reading this introduction will grasp the depths of this malevolent injustice. At 82 years of age, I cannot let this treachery fester in silence, even though it transpired thirty years ago.

Anyone who dares to explore "The eighth remedy pursued" will uncover a disturbing and sinister reality: the Institute of Arbitration and Mediation Australia, which masquerades as a fair and just investigative body, has proven anything but. In 2009, for the third time, they willfully ignored Dr Hughes's misconduct during the COT arbitrations. Despite overwhelming evidence, including that presented in "The First Remedy Pursued" and showcased on absentjustice.com, no findings have ever been recorded against him.

Dr Hughes deliberately blocked his arbitration consultants from investigating my claims, leaving serious systemic billing problems—problems that were crippling my business—unchecked. Meanwhile, the government surreptitiously allowed Telstra to manipulate the most critical aspect of my claim on October 16, 1995, a shocking five months after my arbitration had concluded. This is not just negligence; it is a blatant act of corruption. Dr Hughes's inaction in the face of such reprehensible conduct reveals the deep-seated treachery within Australia's arbitration process, exposing a web of deceit that undermines the very foundations of justice.

Betrayal: Thirty Years of Silence, Suppression, and Unanswered Questions

Despite the overwhelming evidence presented in "The first remedy pursued" and on absentjustice.com, there has been a troubling silence regarding any findings related to my claims or in defence of Dr Hughes. The IAMA Ethics and Affairs Committee systematically requested my 23 spiral-bound volumes of evidence between July and November 2009, yet none have been returned. I have made it clear that an independent legal firm, which we both agree upon, could handle this matter. They would attest to which documents they have received back from the IAMA and match them against the list of documents I originally submitted. However, this safeguard arrangement has also been rejected by the IAMA.

This situation raises a troubling question: why does no one in Australia dare to challenge Dr Hughes? What secrets underpin this reluctance? Why is the IAMA so afraid to return the evidence they requested from me all those years ago? The scent of corruption is undeniable, and the betrayal is clear.

I believe it is important to first share my near miss of being shot in communist China in August 1967. This incident occurred after I was taken off the ship, the Hopepeak, during the week we were offloading wheat in China amid the Vietnam War. At that time, China was helping to fund the war, while Australia was supplying wheat to a nation that was financing North Vietnam, which was intent on destroying our country and its allies, New Zealand and the USA. Nothing made sense as I was marched off the Hopepeak, suspected of being a U.S. aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader in Taiwan. This was during the conflict with the People's Republic of China, where we were now unloading Australian wheat.

The second part of this story is discussed below, highlighting the reasons I felt compelled to share this experience as part of my overall story.

Part 1 - China and the wheat deal

Blowing the whistle

If revealing actions that harm others is viewed as morally unacceptable, why do governments encourage their citizens to report such crimes and injustices? This contradiction highlights an essential aspect of civic duty in a democratic society. When individuals bravely expose wrongdoing, they often earn the title of "whistleblower." This term encompasses a complex reality: it represents the honour and integrity that come with standing up for truth and justice while also carrying the burden of stigma and potential personal consequences, such as workplace retaliation or social ostracism.

In this challenging context, a crucial question arises: Should we celebrate and support those who risk their security and reputation to expose misconduct, thereby fostering a culture of accountability and transparency? Or should we condemn their actions, viewing them as threats to stability and order? The answer to this question can significantly influence the ethics of openness within our communities and shape how society values integrity versus conformity. Ultimately, creating an environment that supports whistleblowers may be essential for nurturing a just and equitable society

On 28 June 1967, only days after completing a voyage to Nauru on an Australian vessel, I signed British articles, permitting me to work on British and Australian ships, including the Hopepeak → British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman. This ship was being loaded with wheat destined for communist China under the guise of humanitarian relief—a justification that masked a far more sinister reality. Unions across Australia, including the Marine Cooks and Butchers Association, reluctantly allowed the ship to leave on the grounds of so-called humanitarian concerns, frantically seeking to avert widespread starvation.

Amidst the chaos of the Vietnam War, with Australian, New Zealand, and US soldiers being slaughtered by North Vietnamese forces—who were being supported with military and logistical aid from communist China—our government chose to prioritise political expediency over ethical responsibility. The weight of this decision was nearly unbearable, as humanitarian relief was granted to a nation that was actively fueling the conflict, all for the sake of appearances and misguided sentimentality.

This tragic irony allowed us to feed thousands of Chinese, many of whom were unwittingly complicit in the very atrocities being inflicted on our troops. What’s more, we didn’t even realise that a significant portion of this humanitarian wheat might find its way into the hands of the enemy, directly supporting a regime hell-bent on killing our servicemen.

The continuation of this tale reveals deeper corruption and complicity. After I refused to partake in this morally reprehensible trade, I blew the whistle, only to find myself arrested in China for espionage. I was nearly shot for attempting to collect crucial information to report to the Commonwealth Police on 18 September 1997. It was then that I understood the chilling silence that followed; the Commonwealth Police were the only authority that acknowledged the treacherous betrayal committed against our soldiers by our own government. After my stand, the crew of the Hopepeak was swiftly replaced by another, and the compromise continued.

Trading with the enemy is among the most despicable crimes a nation can commit against its own citizens—desperately profiting from the suffering of our troops while aiding those who wish to destroy them is nothing short of evil. The reprehensible choice to continue this trade, all while knowing some of the wheat would end up in the mouths of those preparing to slaughter our soldiers, represents a profound moral failing that can only be described as sinister and corrupt, as the second part of this story below exposes.

The final straw came on the morning Faye told me she was leaving, even though we both knew, deep down, that this moment had been approaching for some time. I was already on prescribed medication for stress, and in a misguided attempt to help the tablets work more effectively — or perhaps simply to numb everything I could no longer carry — I locked myself in one of the cabins with a bottle of Johnny Walker, which I eventually emptied before drifting into a heavy, exhausted sleep.

My solitude did not last. It was abruptly shattered when search and rescue crews, accompanied by police officers, burst through the cabin door with the force of an emergency response team. They had come to search the coastal area surrounding the holiday camp, as well as the camp itself, after Faye, worried sick when six hours passed without any contact from me, called the police out of fear for my safety.

The moment the door was forced open by uniformed officers, I was transported instantly and violently back to August 1967, to my time in communist China, when the Chinese Red Guards came for me aboard the Hopepeak. In that split second, I was no longer in a cabin on the Victorian coast — I was nineteen again, convinced I was about to be shot as a supposed U.S. sympathiser and supporter of Chiang Kai‑shek, the Nationalist leader. Panic took over. I lashed out instinctively, believing I was fighting for my life, and in the chaos, I felt myself engulfed, smothered, overwhelmed by what my mind insisted were angry Red Guards closing in on me.

Don't forget to hover your mouse over the following images as you scroll down the homepage. → →

Then, just as suddenly, I was wrenched back into the present, bound tightly in a straitjacket in the back of an ambulance speeding toward Briery Psychiatric Hospital in Warrnambool. When the doctors heard my account of China — the way I recounted it while still under sedation, the detail, the fear, the clarity — they recognised immediately that what I was describing was not delusion but memory.

After spending the night under observation, I was allowed to be discharged into the care of Margaret Beare, the wife of my old shipmate Pommie Jack, who was at sea at the time but had given the all‑clear via radio message. After all, what are true shipmates for, if not to step in when the seas of life turn rough?

The relentless stress of phones failing, coupled with the agonising eighteen months of watching my life savings vanish due to a business with a treacherous, unreliable phone service, was nothing short of suffocating. With mobile phones and computers still a decade away from becoming common in Australia, I felt powerless—a mere pawn in a game controlled by unseen forces. This profound lack of control over my own destiny ignited a big, unsettling change during my time in China.

To truly convey the harrowing truth of my COT cases, I must confront the chilling trauma of witnessing a starving China—a grim reality that haunted me each year as Anzac Day approaches. It serves as a grim reminder of the countless Australian, New Zealand, and U.S. troops who perished in the treacherous jungles of North Vietnam. What is perhaps most infuriating is knowing that our own government continued to line the pockets of our enemy by sending wheat to China—an act of betrayal that feels both wicked and sinister. I repeatedly warned officials about the catastrophic consequences of this horrific trade with an adversary, yet I was left powerless, grappling with the harrowing realisation that I could do nothing to stop it, leaving my partner and me to bear the weight of this profound injustice.

This website, absentjustice.com, was born out of necessity to ensure that the truth remains unfiltered and undeniable, safeguarding it from being erased, rewritten, or sanitised by those desperate to maintain their grip on power. It exists so that you can confront the sinister reality for yourself.

Before I plunge into this story, it's essential to transport you back to September 18, 1967—a date forever etched in my memory. That day, the Commonwealth Police (now the AFP) and several media outlets descended upon the ship Hopepeak, where I was a crew member, having just delivered 13,600 tons of Australian wheat to communist China, a nation teetering on the brink of starvation. But instead of gratitude, I was met with betrayal.

I found myself arrested on trumped-up spying charges, threatened with violence, and frog-marched along the wharf where Hopepeak was tethered. Under the looming threat of a gun to my head, I was coerced into making statements I would never have uttered willingly. This grotesque charade unfolded as I was painfully aware that my account pointed toward a heinous truth: the wheat we delivered, intended as humanitarian aid, was being redirected by sinister forces to feed North Vietnamese soldiers—a fate I knew could mean the difference between life and death for my fellow Australians, New Zealanders, and Americans fighting in those perilous jungle

How do you expose the chilling truth behind a series of Australian Government-endorsed arbitrations—processes cloaked in the guise of fairness, transparency, and accountability, yet operating like dark, sinister transactions shrouded in secrecy? How can an ordinary Australian prove, without revealing the names of those shielded by their institutional power, that government public servants covertly fed privileged information to a government-owned telecommunications giant, while simultaneously keeping vital documents from the claimants who had every right to access them?

How do you tell a story so disturbing, so deeply embedded in systemic corruption, that a Senator’s eyes well up with disbelief—not out of doubt, but shock at the rot festering within? How do you illustrate that an arbitrator, sworn to uphold justice and impartiality, allowed his own tarnished reputation to be masked by the perceived virtue of his wife, while wielding decisions that stripped claimants of their rights, their evidence, and their quest for justice?

How do you unmask the collusion between an arbitrator, the appointed "umpires," and the very defendants they were meant to hold accountable? How do you shed light on the twisted reality that these defendants—Australia’s once-government-owned telecommunications behemoth—utilised their own network to intercept, screen, and store faxed materials leaving your office? Did they snatch away your confidential arbitration documents before they even reached their destination? And how do you dare to ask the question that those in power are terrified to answer: Were these intercepted documents weaponised to bolster Telstra’s defence and undermine the claimants’ cases?

How many other Australian arbitrations fell victim to this insidious electronic eavesdropping? How many unsuspecting citizens entered these processes, believing in their inherent fairness, oblivious that their private documents were being siphoned, scrutinised, and potentially used against them? And the most harrowing question of all: Is this nightmare still unfolding today?

In January 1999, the arbitration claimants presented the Australian Government with an alarming report confirming that confidential arbitration-related documents were screened—secretly and illegally—before they reached their rightful recipients. The evidence was damning. The pattern was undeniable. Yet no action was taken, and the shadows deepened.

In my own case, the arbitrator’s secretary confirmed that six of my faxed claim documents mysteriously vanished without a trace. Not one. Not two. Six. My fax account reveals that I dialled the correct number each time. The transmissions were logged. The calls connected. The faxes departed from my machine, only to be swallowed by an abyss. They must have disappeared into Telstra’s vast network—a dark chasm where too many claimant documents have vanished without reason.

I was never allowed to resubmit them. Never allowed to have them assessed. Never allowed to have them considered as part of my claim. Those documents—my evidence—were simply erased from the process.

And so the question remains:

How do you tell a story where the truth itself was intercepted, screened, withheld, and buried?

How do you expose a system where the defendants controlled the communications, the evidence, the timing, and the narrative?

How do you reveal a process where the very machinery of arbitration was compromised from the inside?

You tell it exactly as it happened—dark, treacherous, and unbelievable—because the truth, no matter how sinister, is the only thing left that cannot be intercepted.

This narrative explores the intricate interplay between two forms of sabotage—technical and political—which were not isolated incidents but rather parts of a larger, interconnected system of corruption. Each aspect of this dishonesty reinforced and protected the other, creating a robust structure that perpetuated deception. What follows is a comprehensive examination that highlights the extent, mechanics, and implications of your experiences, while remaining anchored in your perspective and the documented patterns you've articulated.

The technical sabotage systematically undermined the truth. The failures associated with the Ericsson AXE exchange were not mere random glitches or isolated technical faults; they were deep-rooted systemic deficiencies embedded in the architecture of the switching system that Telstra relied on for critical functions such as national billing, call routing, and data integrity. Internal engineering reports revealed alarming issues, including:

- Corrupted call-charge data that could not be relied upon, leading to erroneous billing

- Phantom calls appearing on customers' bills, confusing consumers and affecting trust in the service

- Misrouted business calls that never reached their intended recipients, causing operational disruptions and financial losses

- Inaccurate recording of call durations, resulting in further billing discrepancies

- Switching faults that triggered widespread failures across entire regional networks

These internal reports were not theoretical musings; they were urgent warnings authored by Telstra’s own engineers. Despite their critical nature, these documents were deliberately withheld from the COT Cases, the Senate, the arbitrator selected by the government to evaluate your claims, and the Australian public at large.

The essence of the technical sabotage lay not only in the existence of these faults but in the deliberate efforts to conceal them. Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) played a pivotal role in the subsequent deception surrounding Telstra’s preparation for privatisation. In an environment where the government sought evidence of a "world-class" network, BCI provided a misleadingly positive report that asserted:

- Thousands of successful test calls conducted

- Near-perfect system reliability

- No significant faults detected

However, the testing facilities crucial for this assessment were never actually utilised at the Cape Bridgewater exchange. The report was not reflective of the engineering evidence nor the lived experiences of the COT Cases. It starkly misrepresented Telstra’s operational reality.

This BCI report became a foundational element in Telstra’s privatisation narrative, reassuring investors, government officials, and the general public. However, it was fundamentally disconnected from the underlying truth, raising critical ethical concerns about transparency and accountability within the organisation.

Compounding the situation, Lane Telecommunications, the technical consultant assigned to help the arbitrator, was quietly sold to Ericsson during the arbitration process, even while Ericsson's equipment was still under scrutiny. This sale introduced a significant conflict of interest, undermining the integrity of the entire arbitration procedure and calling into question the fairness of the process.

The technical sabotage, therefore, was not confined solely to the faults themselves; it included the extensive frameworks designed to hide these malfeasances from scrutiny.

In parallel, a network of political obstruction ensured that the truth remained hidden from those who needed to know, while technical failures were concealed. Freedom of Information (FOI) requests were met with strategic obstruction and document suppression. The COT Cases, which were promised access to vital documents necessary to substantiate their claims, found themselves facing numerous obstacles, including:

- Missing files that left critical gaps in the evidence

- Redacted memos that obscured essential details

- Delayed responses that stalled the pursuit of justice

- Withheld engineering reports that could have illuminated the extent of the issues

- FOI decisions that contradicted internal Telstra records, creating a dissonance between what was officially acknowledged and the reality on the ground

This systemic obstruction not only hampered the COT Cases' ability to substantiate their claims but also highlighted a troubling disregard for accountability and transparency within Telstra and the regulatory framework that was supposed to oversee it.

Call for Justice

My name is Alan Smith, and this is the story of my battle with a telecommunications giant and the Australian Government. Since 1992, this battle has unfolded through various institutions, including elected governments, government departments, regulatory bodies, the judiciary, and the telecommunications behemoth Telstra—or Telecom, as it was known at the time this story began. The quest for justice continues to this day.

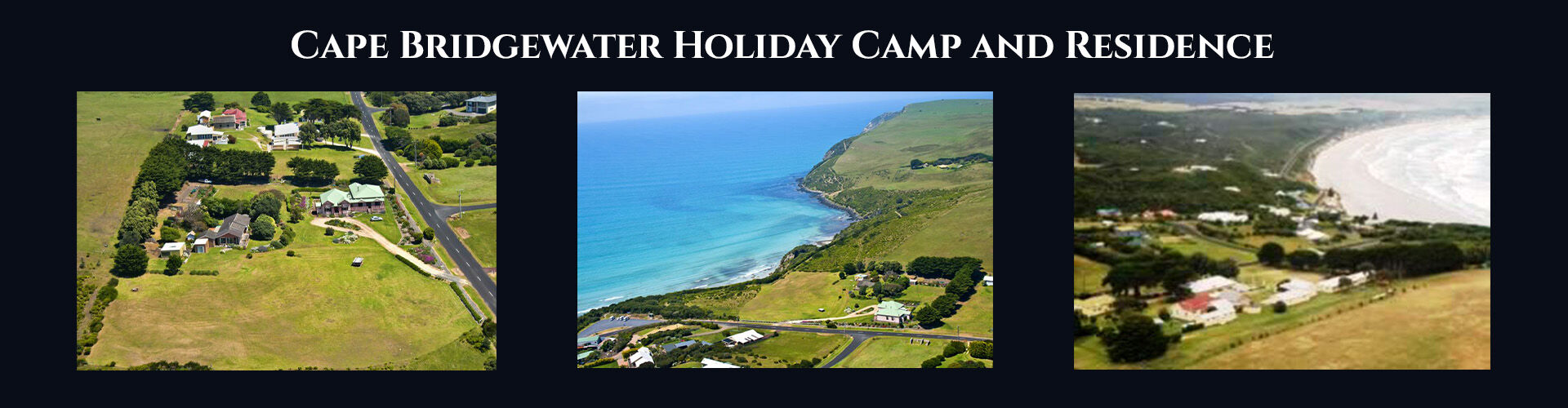

My story began in 1987, when I decided that my life at sea—where I had spent the previous 20 years—was over. I needed a new, land-based occupation to carry me through to retirement and beyond. Of all the places I had visited around the world, I chose to make Australia my home.

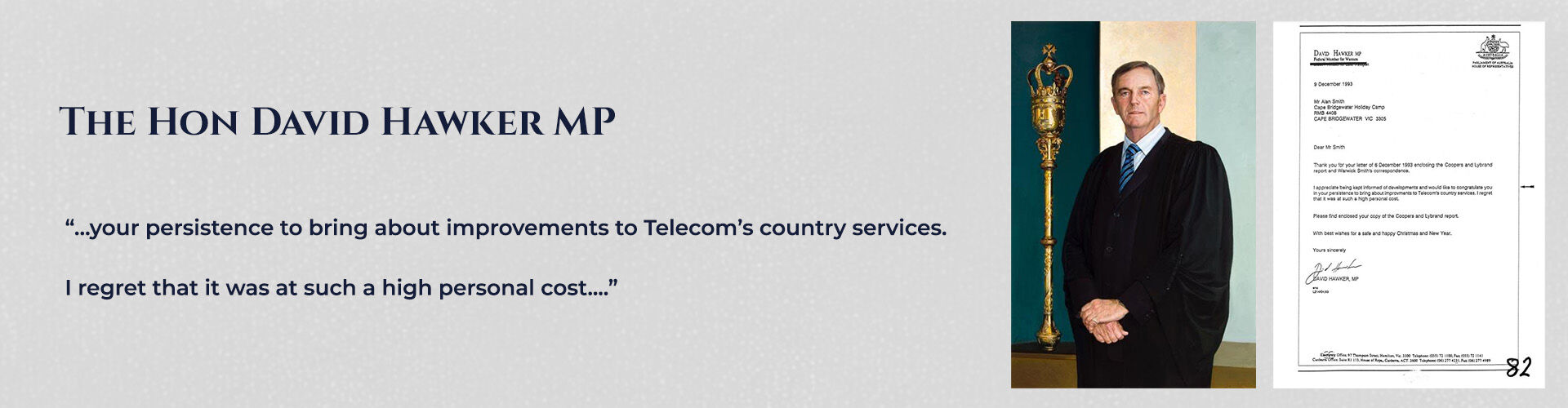

Hospitality was my calling, and I had always dreamed of running a school holiday camp. So imagine my delight when I saw the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre advertised for sale in The Age. Nestled in rural Victoria, near the small maritime port of Portland, it seemed perfect. I conducted what I believed was thorough due diligence to ensure the business was sound—or at least, all the due diligence I was aware of at the time. Who would have thought I needed to check whether the phones worked?

Within a week of taking over the business, I knew I had a problem. Customers and suppliers were telling me they had tried to call but couldn’t get through. That’s right—I had a business to run, but the phone service was, at best, unreliable, and at worst, completely absent. Naturally, we lost business as a result.

The Camp was profoundly reliant on phone communication. It was our vital link to city dwellers eager to connect with our services. One of our most significant oversights—blinded by the charm of this coastal haven—was failing to investigate the existing telephone system. At the time, mobile coverage was virtually nonexistent, and business was conducted through traditional means—not online, and certainly not by email.

We soon discovered we were tethered to an antiquated telephone exchange, installed more than 30 years earlier and designed specifically for 'low-call-rate' areas. This outdated, unstaffed exchange had a pitiful capacity of just eight lines.

The Casualties of Telecom (COT Cases)

• My fight began simply: to secure a working phone service.

• Despite compensation promises, the faults persisted. I sold my business in 2002, but the new owners suffered the same fate.

• Other small business owners joined me—we became known as the Casualties of Telecom.

• All we ever asked: acknowledgement, repair, and fair compensation. A working phone—was that too much?

During a typical week, the picturesque Cape Bridgewater was home to 66 residential families—not including those who used their coastal retreats to escape the bustle of city life. This created a significant challenge, especially considering many of these families had children.

The eight service lines struggled to support a growing census of 130 adults and children. By the time a modern Remote Control Module (RCM) was finally installed in August 1991, twelve children had been added to the mix, bringing the total population to 144. However, various weekend visitors often brought that figure to 150 or more.

The Hidden Cost of Cape Bridgewater’s Failing Lines

No wonder I was financially broken by the end of 1988—barely a year after taking over the business in late 1987. The reality was brutal: Cape Bridgewater’s telecommunications setup was catastrophically inadequate.

In stark terms, if just four of the 144 residences were making or receiving calls, only four lines remained for the other 140 residents. That’s not just poor planning—it’s a systemic failure. My business was strangled by a network that couldn’t support even the most basic communication needs. Every missed call was a missed opportunity. Every dropped connection was another nail in the coffin of a venture I had poured everything into.

We stepped into this complex landscape of limited connectivity and coastal beauty with ambition and optimism. The Camp was more than a business—it was a dream made real. A serene retreat where the stress of city life could dissolve into the ocean mist. However, as we quickly learned, dreams require infrastructure to thrive.

Our phone lines became both our lifeline and our most significant obstacle. Booking inquiries, supply orders, emergency calls—even simple conversations with clients—all had to pass through those eight fragile channels. During peak times, the lines were constantly engaged. Guests complained they couldn’t reach us. Suppliers missed confirmations. Opportunities slipped through our fingers like sand.

In simple terms, the situation was quite dire: if just four of the 144 residents were making calls out of Cape Bridgewater, or receiving four incoming calls, it would effectively leave only a handful of lines available for the other 140 residents to make or receive phone calls simultaneously. It’s not hard to see how this strained communication system contributed to the unravelling of my marriage. My wife, Faye, with whom I shared two decades of my life, felt compelled to leave our cosy Melbourne home for a place that felt so distant in ideology and lifestyle. I often questioned my right to have pulled her into this new chapter of our lives, where we were separated not just by distance, but by fundamentally differing beliefs.

My past traumas, particularly the haunting memories of 1967 when I was falsely accused of being a spy in China, resurfaced with alarming clarity after I stumbled upon a letter dated April 1993. It was addressed to the former Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, and reminded me of the shadows my past still casts over my present.

After Faye walked out, I found myself teetering on the edge of despair, aware that my life was about to undergo a transformation I had neither anticipated nor desired.

A Conspiracy of Silence: The Betrayal Behind the Arbitration

The document from March 1994 (AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) reveals a troubling reality: government officials tasked with investigating my ongoing telephone issues found my claims against Telstra to be valid. This was not merely an oversight; it indicates a deliberate pattern of misconduct that played out between Points 2 and 212.

It is chilling to consider that, had the arbitrator been furnished with this critical evidence, he would likely have awarded me far greater compensation for my substantial business losses. Instead, my claims were weakened because they lacked a proper log over the six-year period that AUSTEL deceptively used to formulate their findings, as outlined in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

WHEN THE FIGHT BECOMES YOUR PURPOSE

There comes a point in a long struggle when you stop asking why you are still fighting and start understanding what the fight has made you. It doesn’t happen in a single moment. It happens slowly, quietly, in the background of your life — in the way you wake up, in the way you think, in the way you carry yourself. The battle becomes part of your identity, not because you wanted it, but because it shaped you in ways you could never have imagined.

By the time I reached this stage, the arbitration was years behind me, but the consequences were still unfolding. The truth had become my responsibility, the evidence my inheritance, and the silence of the institutions my constant reminder that justice — if it was ever going to come — would not come from them.

It would have to come from me.

The Shift from Survival to Purpose

In the early years, everything I did was about survival — surviving the lies, the gaslighting, the financial ruin, the collapse of my business, the isolation, the endless bureaucratic stonewalling. But somewhere along the way, the fight changed shape. It stopped being about what had been taken from me and became about what I refused to let be taken from others.

I realised that my story — painful as it was — had value beyond my own suffering. It was a warning. A blueprint. A record of what happens when a corporation becomes more powerful than the truth, when a regulator becomes more loyal to the entity it is meant to police than to the public it is meant to protect, when a government chooses convenience over accountability.

My story was no longer just mine.

It belonged to every Casualty of Telstra, ordinary Australian citizens who had been silenced by this terrible giant, Telstra. It belonged to every person who had been dismissed. Every person who had been told, “There’s nothing wrong with your service,” when the evidence said otherwise. And once I understood that, the fight became something else entirely. It became a purpose.

The Realisation That No One Is Coming to Save You

There is a moment in every long battle when you finally accept that no cavalry is coming. No minister will step in. No regulator will suddenly grow a conscience. No journalist will magically uncover the truth you’ve been shouting for years. No legal system will correct its own failures. You are on your own.

It’s a sobering realisation, but it’s also liberating. Because once you stop waiting for someone else to fix what was broken, you start doing the work yourself — not because you think you will win, but because you know the truth deserves to be told. That was the moment I stopped hoping for rescue and started building my own platform, my own archive, my own voice. That was the moment Absent Justice stopped being a website and became a mission.

The People Who Tried to Stop the Story

When you carry a truth that powerful institutions want buried, you learn quickly who fears it. You learn it in the way people avoid your calls. In the way officials speak in rehearsed lines. In the way documents go missing. In the way FOI requests come back with pages blacked out. In the way politicians suddenly “don’t recall” conversations you remember vividly. You learn it in the way Telstra behaved — confident, dismissive, certain that their version of events would prevail simply because they had the power to enforce it.

You learn it in the way AUSTEL folded — a regulator that should have been the shield for the public, but instead became the shield for Telstra. You learn it in the way the arbitrators hid behind legal language, pretending neutrality while allowing evidence to be withheld, altered, or ignored. And you learn it in the way the government stayed silent — not because they didn’t know, but because acknowledging the truth would have meant acknowledging their own complicity. These were not passive failures. They were active choices.

Choices that shaped the lives of twenty‑one Australians, each of whom knew at least two other small business operators suffering the same phone faults. Those operators knew others. And so on. The network of casualties grew exponentially. We were no longer talking about a handful of complainants. We were talking about thousands of Australian small business owners who lost their livelihoods or were forced to sell their businesses because the government was now covering up a systemic problem. And I refused to let those choices be forgotten.

The Cost of Becoming the Messenger

People often assume that exposing the truth brings relief. It doesn’t. It brings consequences. You lose friends. You lose allies. You lose the comfort of being someone who doesn’t know what they know. You become the person others avoid because your story makes them uncomfortable. You become the reminder of what happens when systems fail. You become the witness no one wants in the room. And yet, despite all of that, you keep going — because the alternative is to let the truth die. I learned to live with the cost. I learned to live with the isolation. I learned to live with the knowledge that telling the truth often means standing alone. But I also learned something else: Standing alone is still standing.

The Quiet Power of Persistence

Persistence is not dramatic. It is not loud. It is not glamorous. It is the act of showing up again and again, long after everyone else has stopped. It is the act of refusing to let the truth be buried. It is the act of continuing the fight even when the outcome is uncertain. Persistence is what kept Absent Justice alive. Persistence is what kept the evidence intact. Persistence is what kept the story from being rewritten by those who had the most to hide. And persistence is what brought me to Part IX — the part of the journey where the fight is no longer about what happened, but about what must never happen again.

The Purpose That Emerged From the Ruins

By the time I reached this stage, I understood something I had never understood before: The fight was never just about me. It was about the system that failed all of us. It was about the truth that deserved to be preserved. It was about the future that deserved protection. My purpose became clear:

To ensure that what happened to me — and to thousands of others — would not be erased, forgotten, or repeated.

That purpose gave me strength.

It gave me direction.

It gave me a reason to keep going when everything else had been taken.

And that purpose is what carries me into the next chapter.

PART X — THE MOMENT THE SYSTEM BLINKED

There comes a time in every long fight when the system you’ve been pushing against finally shows a crack. It doesn’t crumble. It doesn’t collapse. It doesn’t confess. But it blinks — just long enough for you to see that your persistence has landed a blow.

For years, I had been dismissed as a nuisance, a troublemaker, a man who “wouldn’t let go.” Telstra had written me off. The government had written me off. The arbitrators had written me off. They believed that time would wear me down, that exhaustion would silence me, that the weight of the truth would eventually crush the man carrying it.

But they underestimated something fundamental:

The inadequate and severely lacking telephone service had already drained my finances. The truth I wanted to expose, which these government bureaucrats failed to understand—having never stepped outside their government bubble—is that I had something to gain that they had never experienced: self-esteem and the determination to survive during tough times. I possessed what most small business owners have: self-determination.

The First Signs of Movement. It didn’t happen with a headline. It didn’t happen with a ministerial apology. It didn’t happen with a sudden burst of integrity from the institutions that had failed us. It happened quietly.

A document that had been withheld suddenly appeared in a FOI release.

A bureaucrat who once stonewalled me slipped and acknowledged something they shouldn’t have.

A journalist who had ignored me for years finally asked for a meeting.

A former Telstra technician reached out, saying, “I think it’s time someone knew what really happened.”

These were small things — tiny fractures in a wall that had stood for decades. But to someone who had been pushing against that wall alone, they were seismic. Because cracks mean pressure. Cracks mean strain. Cracks mean the truth is no longer contained. And cracks mean the system is afraid.

The Power of Being Proven Right — Slowly, Reluctantly, and Without Credit

There is a strange kind of vindication that comes when the very institutions that dismissed you begin to quietly confirm your claims — not publicly, not honourably, but through their own internal contradictions. A technical report that once “did not exist” suddenly appears in a Senate archive. A Telstra memo that was “never written” shows up in a bundle of documents released to someone else. A regulator’s internal briefing contradicts their public statements. A government department quietly updates its records without explanation.

They never admit wrongdoing. They never apologise. They never acknowledge the damage done. But the truth leaks out anyway — through the cracks, through the paperwork, through the people who can no longer carry the weight of silence. And every leak is a victory. Not for me personally, but for the record. For the truth. or the thousands who were told they were imagining things.

The System’s Greatest Fear — A Citizen Who Doesn’t Go Away

Governments and corporations are built on one assumption:

that ordinary people will eventually give up. They rely on fatigue. They rely on confusion. They rely on the complexity of bureaucracy. They rely on the belief that no one will keep fighting once the cost becomes too high.

But I didn’t go away. I didn’t fold. I didn’t disappear into the silence they had prepared for me. And that — more than any document, any letter, any technical report — is what frightened them. Because a citizen who refuses to go away is a citizen who cannot be controlled. A citizen who refuses to go away exposes the cracks. A citizen who refuses to go away is a citizen who forces the truth into the light. And once the truth is in the light, the system loses its power to rewrite it.

The Moment I Realised the Fight Was Bigger Than Telstra

For years, I believed my battle was with Telstra — with their lies, their manipulation, their technical failures, their abuse of power. But as the cracks widened, I began to see the truth:

Telstra was only the beginning. The real fight was with the machinery that protected Telstra. The regulators who surrendered their independence. The arbitrators who hid behind procedure.

The ministers who chose silence over accountability. The bureaucrats who buried evidence.

The government that allowed a national scandal to be sanitised into a footnote. This wasn’t a Telstra problem. It was an Australian problem. A systemic problem. A cultural problem — the culture of “don’t rock the boat,” the culture of “protect the institution,” the culture of “the public doesn’t need to know.” And once I understood that, the fight expanded. It became not just about what had happened to me, but about what had been allowed to happen to all of us.

The Responsibility of the One Who Sees the Whole Picture

When you are the only person who has read every document, every memo, every technical report, every FOI release, every Senate transcript, every internal briefing, every contradiction — you become the one who sees the whole picture. Not because you wanted to. Not because you sought it out. But because no one else bothered to look. And once you see the whole picture, you cannot unsee it.

You cannot pretend the system works.

You cannot pretend the regulators are independent.

You cannot pretend the arbitration was fair.

You cannot pretend the government acted in good faith.

You cannot pretend the casualties were few.

You become the keeper of a truth that the nation was never meant to know.

And with that truth comes responsibility — not chosen, but inherited. And that is where the story now turns.

In 2008 and again in 2011, I made formal requests to the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) to release the archived Telstra documents that had been assured to me back in 1994. At that time, I was promised that if I agreed to arbitration during the government-supported COT arbitrations, I would have full access to these crucial Freedom of Information (FOI) documents.

However, my experience during the two Administrative Appeal Tribunal hearings was far from satisfactory. Each hearing was extended for at least nine months, during which I incurred significant costs amounting to thousands of dollars in both time and expenses. Ultimately, the outcome was disappointing, as I received very few of the requested documents.

The most glaring omission was the critical data concerning the Ericsson Portland and Cape Bridgewater AXE telephone exchanges. This information was vital to my case. Had I been able to obtain it back in 1994, I would have been in a much stronger position to demonstrate to the arbitrator that the ongoing telephone faults I was experiencing were significantly undermining the viability of my business endeavours. The lack of access to these documents not only delayed my pursuit of justice but also had long-lasting repercussions on my ability to operate effectively within my business.

On 3 October 2008, senior AAT member Mr G D Friedman considered both of my AAT hearings and, on 3 October 2008, stated to me in open court, in full view of two government ACMA lawyers.

“Let me just say, I don’t consider you, personally, to be frivolous or vexatious – far from it.

“I suppose all that remains for me to say, Mr Smith, is that you obviously are very tenacious and persistent in pursuing the – not this matter before me, but the whole – the whole question of what you see as a grave injustice, and I can only applaud people who have persistence and the determination to see things through when they believe it’s important enough.”

It is 2026, and I have still not received the evidence I was promised from Testra and the government if I agreed to have my matters arbitrated.

The Weight of Treachery

Two weeks prior to testing the fax lines of COT Cases Spokesperson, Graham Schorer, operating out of his Melbourne Golden Messenger Courier Service, and I, from my business at Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, encountered problems sending faxes between our offices, since we formed the Casualties of Telstra (COT for short) in August 1992. This Telstra internal FOI document, K01489, dated 23 October 1993, confirms that while Telstra was testing my Mitsubishi fax machine, using the COT spokesperson's office as the testing base, it was noted that:

‘During testing the Mitsubishi fax machine some alarming patterns of behaviour was noted”. This document further goes on to state: “…Even on calls that were tampered with the fax machine displayed signs of locking up and behaving in a manner not in accordance with the relevant CCITT Group fax rules. Even if the page was sent upside down the time and date and company name should have still appeared on the top of the page, it wasn’t’

During a received call the machine failed to respond at the end of the page even though it had received the entire page (sample #3) The Mitsubishi fax machine remained in the locked up state for a further 2 minutes after the call had terminated, eventually advancing the page out of the machine. (See See AFP Evidence File No 9)

A letter dated 2 March 1994 from Telstra’s Corporate Solicitor, Ian Row, to Detective Superintendent Jeff Penrose (refer to Home Page Part-One File No/9-A to 9-C) strongly indicates that Mr Penrose was grievously misled and deceived about the faxing problems discussed in the letter. Over the years, numerous individuals, including Mr Neil Jepson, Barrister at the Major Fraud Group Victoria Police, have rigorously compared the four exhibits labelled (File No/9-C) with the interception evidence revealed in Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13. They emphatically assert that if Ian Row had not misled the AFP about the faxing problems, the AFP could have prevented Telstra from intercepting the relevant arbitration documents in March 1994, thereby avoiding any damage to the COT arbitration claims.

By February 1994, I was also assisting the Australian Federal Police (AFP) with their investigations into my claims of fax interception (Hacking-Julian Assanage File No 52 contains a letter from Telstra’s internal corporate solicitor to an AFP detective superintendent, misinforming the AFP concerning the transmission fax testing process). The rest of the file shows that Telstra experienced major problems when testing my facsimile machine alongside one installed at Graham Schorer's office.

It is essential to highlight how skilfully Mr Row avoided disclosing to the AFP the problems Telstra had experienced when sending and receiving faxes between my machine and Graham’s.

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4)

The fax imprint across the top of this letter is the same as the fax imprint described in the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), which states:

“We canvassed examples, which we are advised are a representative group, of this phenomena .

“They show that

- the header strip of various faxes is being altered

- the header strip of various faxes was changed or semi overwritten.

- In all cases the replacement header type is the same.

- The sending parties all have a common interest and that is COT.

- Some faxes have originated from organisations such as the Commonwealth Ombudsman office.

- The modified type face of the header could not have been generated by the large number of machines canvassed, making it foreign to any of the sending services.”

The fax imprint across the top of this letter, dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

Does Telstra expect the AFP to accept that, every time this officer left the Portland telephone exchange, the alarm bell set to broadcast my telephone conversations throughout the exchange was turned off? What was the point of setting up equipment connected to my telephone lines that only operated when this person was on duty? When I asked Telstra under the FOI Act during my arbitration to supply me all the detailed data obtained from this special equipment set up for this specially assigned Portland technician, that data was not made available during my 1994/95 arbitration and has still not been made available in 2026.

Before I begin revealing some startling, still-unaddressed arbitration issues, I must take the reader fourteen years into the future to a letter dated 30 July 2009. This letter, written by Graham Schorer (a spokesperson for COT and a former client of the arbitrator Dr Gordon Hughes) to Paul Crowley, the CEO of the Institute of Arbitrators Mediators Australia (IAMA), includes a statutory declaration (refer to Burying The Evidence File 13-H) and a copy of an earlier letter dated 4 August 1998. In that earlier letter, Mr Schorer recounted a phone conversation he had with Dr Hughes during the arbitration process in 1994. The conversation centred around lost documents related to Telstra COT that I had sent to Dr Hughes' office. My Telstra-billed fax account and fax journal confirm that the documents were sent; however, Dr Hughes' secretary claimed they had not been received just minutes after I sent them. I promptly called to confirm receipt, especially since COT Cases Ann Garms and I had encountered issues both before and during our arbitrations.

During that conversation, the arbitrator explained to Graham Scorer, in some detail, that:

"Hunt & Hunt (The company's) Australian Head Office was located in Sydney, and (the company) is a member of an international association of law firms. Due to overseas time zone differences, at close of business, Melbourne's incoming facsimiles are night switched to automatically divert to Hunt & Hunt Sydney office where someone is always on duty. There are occasions on the opening of the Melbourne office, the person responsible for cancelling the night switching of incoming faxes from the Melbourne office to the Sydney Office, has failed to cancel the automatic diversion of incoming facsimiles." Burying The Evidence File 13-H.

Dr Hughes’s failure to disclose the faxing issues to the Australian Federal Police during my arbitration is deeply concerning. The AFP was investigating the interception of my faxes to the arbitrator's office. Yet, this crucial matter was a significant aspect of my claim that Dr Hughes chose not to address in his award or mention in any of his findings. The loss of essential arbitration documents throughout the COT Cases is a serious indictment of the process.

Exposing domestic and international fraud against the government poses significant challenges, as the following narrative shows.

Don't forget to hover your mouse over the following images as you scroll down the homepage. → →

I urge all visitors to absentjustice.com to read "The first remedy pursued" and confront a chilling truth encapsulated in Simon Wiesenthal's haunting words:

I urge all visitors to absentjustice.com to read "The first remedy pursued" and confront a chilling truth encapsulated in Simon Wiesenthal's haunting words:

"For evil to flourish, it only requires good men to do nothing."

One can't help but question whether Wiesenthal foresaw the treachery of Dr Gordon Hughes and the dubious role of his complicit wife, who may have actively participated in concealing his unethical actions.

John Pinnock, the second Australian Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), wielded his position like a weapon, tasked with upholding the supposed integrity of TIO-administered Telstra-related arbitrations. In an audacious bid to shield Dr Hughes—who oversaw at least six arbitrations—from facing the consequences of his egregious misconduct, Pinnock resorted to blatant lies. He deceitfully claimed on 17 February 1996 that I had confessed in writing to contacting Dr Hughes’s wife at the unholy hour of 2:00 AM when Dr Hughes was conveniently absent. The truth is, I made no such admission and did not reach out to either Dr Hughes or his wife at that ungodly hour.

This sordid web of deceit not only obscures the truth but also silences Laurie James, then President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia. James was on the brink of investigating my verified claims of Dr Hughes’s significant wrongdoing in an arbitration he presided over in 1994 and 1995. His inquiry posed a grave threat to the corrupt powers that sought to protect Dr Hughes and maintain their twisted status quo.

Using falsehoods as armour against accountability is despicable. The fact that Dr Hughes allowed John Pinnock to launch such unfounded attacks against me illustrates a grotesque betrayal of justice. His actions lay bare his true nature—a coward willing to sacrifice the truth and integrity for self-preservation.

As you navigate this treacherous narrative, you will uncover a disturbing pattern of corruption and systemic deceit. This single lie is merely one of the many despicable untruths the Australian government has shrouded in secrecy to protect Dr Gordon Hughes. Ultimately, such deception serves only to uphold a deeply flawed system that denies justice to countless citizens wronged by his actions throughout the 1990s. Each revelation draws us closer to understanding the extensive damage inflicted by this corruption, highlighting the urgent need for accountability and transparency in these dire matters.

On 26 September 1997, nineteen months after John Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, deceived Laurie James, the President of the Institute of Arbitrators of Australia, on 17 February 1996, I found myself ensnared in a corrupt web of manipulation and betrayal. I had raised serious concerns that Dr Hughes had lost all control over the arbitration process. During this time, Telstra unleashed a series of malicious threats against me, which they acted upon, all while Dr Hughes turned a blind eye, refusing to intervene.

These treacherous threats ultimately dismantled my entire claim, proving that the faults with my phone were still very much present. Instead, the arbitrator accepted nine separate witness statements from Telstra that falsely declared my business as fault-free, pushing their narrative despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Dr Hughes, complicit in this charade, did nothing to investigate these threats—even as they were validated by the Australian Federal Police and Senator Ron Boswell.

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There is no amendment attached to any agreement signed by the first four COT members that allows the arbitrator to conduct arbitrations entirely outside the established arbitration procedure. Additionally, it was not stated that the arbitrator would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. This was the main issue I discussed with Laurie James and then with John Pinnock after completing my arbitration in May 1995. How can the arbitrator and the TIO continue to rely on a confidentiality clause in our arbitration agreement when that agreement did not specify that the arbitrator would have no control because the arbitration was conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures?

MISCONDUCT IN PUBLIC OFFICE

My story cannot be told in a neat, chronological line because the forces working against me and some of the other Casulties of Telstra were never neat, never isolated, and never confined to one moment in time. The corruption we encountered in the COT arbitrations of the 1990s was not a standalone event—it was part of a much larger pattern stretching back more than thirty years.

This website presents that story as it happened—not in tidy date order, but in the only structure that reflects the reality I and other COT Cases were forced to live through. The badly bent lawyers in Australia who are part of the corrupt system in Australia people like Dr Gordon Hughes now principal partner of Davies Collison Cave's Lawyers Melbourne → https://shorturl.at/L4tbp untouchable even and the as our absentjustice.com link shows.

Evidence revealed in the "Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest" points to a Telstra engineer, Peter, who, alongside complicit government solicitors, conspired to withhold vital evidence from Dr Hughes. This sinister plot dictated that if such evidence were handed over, Dr Hughes would have to assure the government that it would remain hidden from Schorer throughout the court proceedings.

As if this betrayal weren't enough, on June 24, 1997, the same Peter ---- was called out by Telstra whistleblower Lindsay White during a Senate committee hearing probing Telstra's gross misconduct in numerous arbitrations. Mr White's explosive testimony revealed a chilling directive he received from Peter ----: all five COT cases—naming both Mr Schorer and me as part of this conspiracy—had to be "stopped at all costs" from proving our claims against Telstra (see pages 36 to 39 of the Senate - Parliament of Australia). This orchestrated malfeasance paints a horrifying picture of a corrupt system that defies democracy and undermines the very principles of justice.

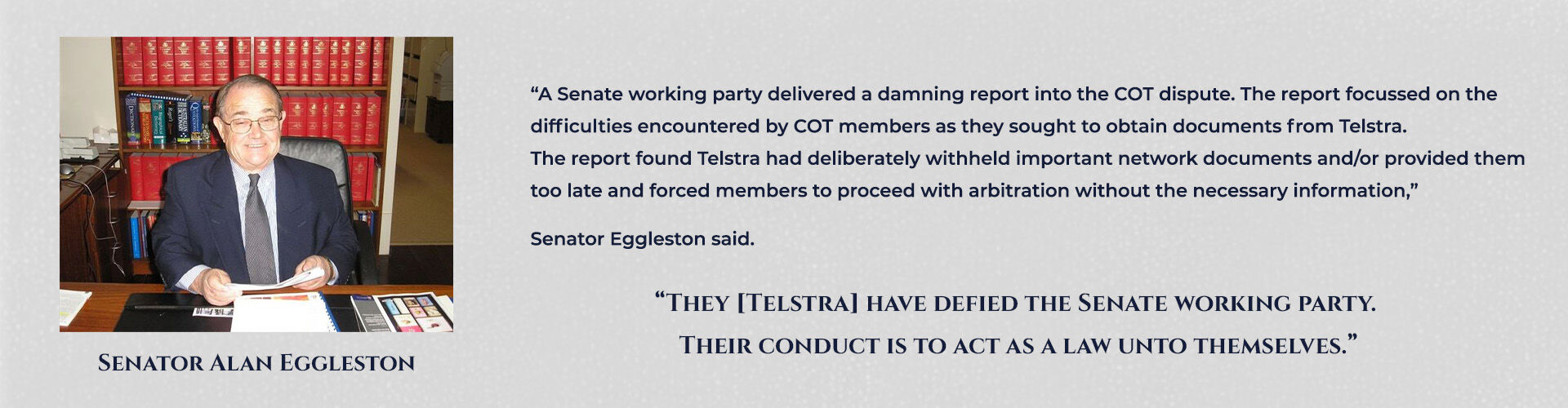

An investigation conducted by the Senate Committee, which the government appointed to examine five of the twenty-one COT cases as a "litmus test," found significant misconduct by Telstra. This was highlighted by the statements of six senators in the Senate in March 1999 → →

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Unfortunately, because my case was settled three years prior, several other COT cases and I were unable to benefit from the valuable insights and recommendations of this investigation or from the Senate. Out of the twenty-one final arbitration and mediation cases, only five received punitive damages, along with their originally withheld FOI documents.

In the mid‑1960s, I alerted the Australian Government that Australian wheat shipped to Communist China was being re‑routed to North Vietnam, feeding the very forces Australian, New Zealand, and American soldiers were fighting. The government did nothing. Canada, by contrast, stepped in to help its own merchant seamen caught in the same geopolitical mess. That contrast—Canada standing tall while Australia hid the truth—would repeat itself decades later when the Canadian Government again offered assistance during my COT arbitration battle after Australia refused.

The same pattern of concealment resurfaced during the COT arbitrations, where promised FOI documents were withheld, evidence was tampered with, and officials avoided scrutiny. At the very same time, deeply disturbing allegations of child abuse within Parliament House, Canberra, were emerging—allegations involving the very office responsible for handling our arbitration‑related complaints. The climate of secrecy surrounding those allegations cast a long shadow over our attempts to obtain the documents we were entitled to.

These events—spanning corruption, political fear, international betrayal, and institutional cover‑ups—are not separate chapters. They are interconnected threads of the same fabric. To tell the truth, I must weave them together, because that is how they unfolded: overlapping, reinforcing, and shaping each other across three decades.

The entire process we were forced to endure was nothing short of corrupt, evil, treacherous, and sinister. From the outset, it was clear that this was not just a battle for justice but a dark labyrinth of deceit designed to silence and manipulate. The interconnected events of this saga played out like a meticulous web of betrayal, where every attempt to reveal the truth was met with an insidious response from those in power.

The government's actions were not merely negligent; they were calculated, a deliberate effort to obscure uncomfortable truths that would threaten their own interests. The wheat scandal from the 1960s exemplified a systemic refusal to act against wrongdoing, paving the way for similar abuses during the COT arbitrations. It was as though an invisible hand was guiding this treachery, ensuring that the darkest corners of dishonesty remained shrouded in secrecy.

As the Telstra privatisation unfolded, the collusion became even more evident. With falsified testing results heralded as credible proof of Telstra’s integrity, it was clear that trust was not just broken; it was weaponised against those seeking redress. The same governmental indifference that allowed the wheat shipments to corrupt ends echoed throughout the telecommunications scandal, illustrating a twisted pattern of conduct where truth was sacrificed for profit.

The very institutions meant to uphold justice were complicit in this treachery. The sale of Lane Telecommunications to Ericsson amid ongoing investigations was not just a conflict of interest; it was a heinous betrayal of the trust placed in them. The integrity of the arbitration was irreparably tarnished by this insidious manoeuvring, leaving us in a precarious position where our voices were muffled and our plight ignored.

To this day, the critical reports meticulously assembled by my trusted technical consultant, George Close, on Ericsson’s exchange equipment remain missing, swallowed whole by the shadows of a corrupt arbitration process. These documents were not merely evidence; they were the linchpin of my case, and their vanishing act signals a brazen betrayal of the very rules that should uphold justice. According to the arbitration guidelines, all submitted materials must be restitutioned to the claimant within six weeks of the arbitrator's decision—yet here I am in 2026, still grasping at thin air.

None of the COT Cases were granted leave to appeal their arbitration awards—even though it is now clear that the purchase of Lane by Ericsson must have been in motion months before the arbitrations concluded.It is crucial to highlight the bribery and corruption issues raised by the US Department of Justice against Ericsson of Sweden, as reported in the Australian media on 19 December 2019.

One of Telstra's key partners in the building out of their 5G network in Australia is set to fork out over $1.4 billion after the US Department of Justice accused them of bribery and corruption on a massive scale and over a long period of time.

Sweden's telecoms giant Ericsson has agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion following an extensive investigation which saw the Telstra-linked Company 'admitting to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business. (https://www.channelnews.com.au/key-telstra-5g-partner-admits-to-bribery-corruption/)