Manipulating the regulator

Here are six examples derived from 151 similar examples that delve into the intricate realm of corruption in government-endorsed arbitrations involving Telstra: 1. **Government Corruption - Gaslighting** www.absentjustice.com/tampering-with-evidence/government-corruption--gaslighting. Explore: This insightful article examines the troubling intersection of government corruption and psychological manipulation, specifically through the lens of the Julian Assange case. It uncovers a complex narrative of control, deceit, and the significant power dynamics at play in the arbitrations. Who truly held the reins during these crucial proceedings? 2. **Who was controlling the arbitrations?** www.absentjustice.com/manipulating-the-regulator/who-was-controlling-the-arbitrations-?Corrupt: This section highlights how certain government practices intensify issues of inequality, poverty, social division, and environmental degradation. It emphasizes the urgency of exposing corruption and demanding accountability from those in power to foster a fairer society. 3. **Contact - Government Corruption** www.absentjustice.com/contact--government-corruptionGet: Stay connected and informed about pressing government corruption issues with Absent Justice. We invite you to reach out and become an active participant in our crucial fight for transparency and accountability in governance. 4. **Chapter 4 Government spying** www.absentjustice.com/australian-federal-police-investigations-1/afp-investigation-2/chapter--4-government-spying. Explore: In this compelling chapter, readers are invited to uncover shocking revelations about government surveillance as detailed in AFP Investigation 2. This investigation seeks to shine a light on the dark side of government spying, underscoring the imperative for transparency and the protection of civil liberties. 5. **Chapter 3 Dishonestly using corrupt government influence** www.absentjustice.com/manipulating-the-regulator/legal-bullying-in-arbitration/chapter-3-dishonestly-using-corrupt-government-influence: Dive into Chapter 3 of 'Tampering with Evidence' to reveal unsettling truths about the manipulation and exploitation of government influence for corrupt purposes. This chapter on Absent Justice takes a hard look at how systemic dishonesty undermines public trust. 6. **Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues** www.absentjustice.com/price-waterhouse-coopers-deloitte/chapter-1-the-collusion-continues: Initiate your journey into the dark underbelly of ongoing collusion in Chapter 1 of 'Unconscionable Conduct.' Here, Absent Justice meticulously uncovers a web of continuous unethical practices, shedding light on the pervasive complicity within institutions.

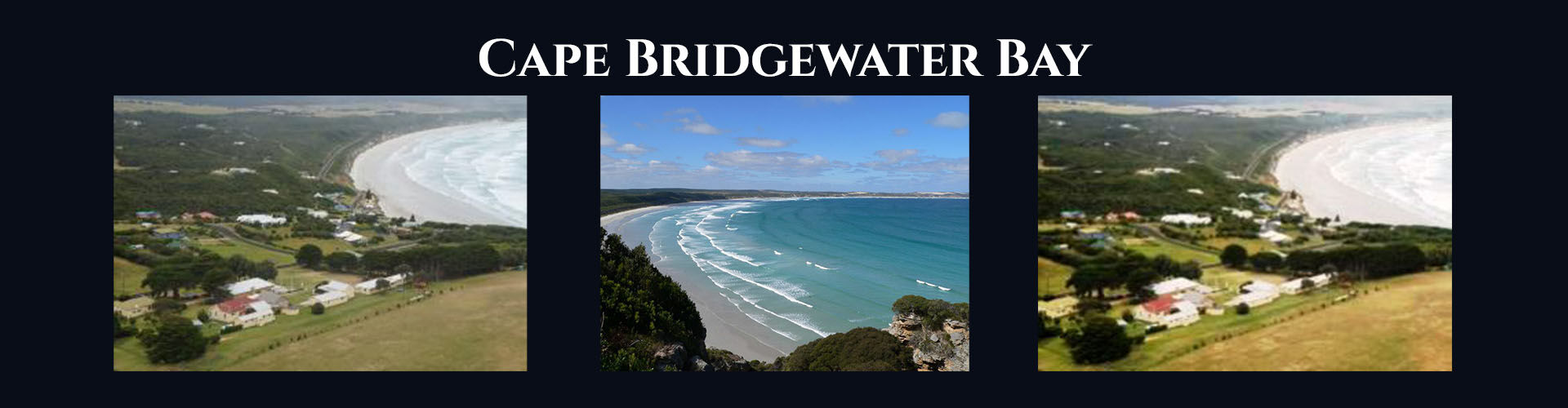

It is evident from Files 51C and 51F Open Letter File No/51-A to 51-G that Gene Volovich, a highly experienced attorney with Law Partners Melbourne, articulated a strong belief that the arbitrator's decision could be annulled on the grounds of a significant failure of natural justice that occurred during my arbitration proceedings. This assertion was made on December 13, 1995, when he served as my initial arbitration appeal lawyer. Ten days later, on December 19, I provided Law Partners with comprehensive copies of the evidence I had previously presented to Darren Kearney, a representative from AUSTEL, the Australian telecommunications authority. Mr. Kearney undertook an extensive five-hour journey from Melbourne to my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, motivated by the importance of reviewing the same critical evidence that had led Mr. Volovich to express his concerns regarding the potential for an appeal.

The circumstances that precipitated this situation emerged when AUSTEL allowed Telstra, a major telecommunications provider, to address contentious billing documents on October 16, 1995. This decision was made outside the established arbitration process and occurred without my presence, as well as that of the arbitrator. Instead of providing accurate and transparent information in their written correspondence, Telstra opted to covertly misrepresent key facts related to my evidence, thereby undermining the integrity of the arbitration process. This prompted officials from AUSTEL to engage in both telephone conversations and written communication with me, inquiring whether they could examine my arbitration claim materials. Notably, these materials had not been subjected to thorough investigation or documented analysis by Dr. Gordon Hughes and his team of technical consultants, despite the explicit requirements set forth in the arbitration rules mandating their adherence by the arbitrator. AUSTEL had previously discussed this procedural violation in their COT Cases report of April 1994 and expressed astonishment that Dr. Hughes had chosen not to comply with these stipulations.

On December 19, after Mr. Kearney had meticulously examined the uninvestigated claim materials at my holiday camp, he respectfully requested permission to transport these documents back to Melbourne for further review. Faced with the gravity of the situation and the status of Mr. Kearney as a government official, it was difficult for me to decline such a request. Although Mr. Kearney provided me with assurances, both in a written format and in person, regarding the government's intent to furnish me with findings related to this outstanding arbitration claim material, I have yet to receive any such findings, leaving my claims unresolved.

As outlined in File 51G, addressed to Senator Ron Boswell from Michael Brereton & Co. lawyers and dated August 10, 1997, I possessed a substantive case against Dr. Hughes. However, despite the validity of my claims and the potential for legal recourse, I found myself unable to secure adequate legal representation or assistance from their office, exacerbating the challenges I faced in my pursuit of a just resolution.

It is evident from Files 51C and 51F Open Letter File No/51-A to 51-G that Gene Volovich, a highly experienced attorney with Law Partners Melbourne, articulated a strong belief that the arbitrator's decision could be annulled on the grounds of a significant failure of natural justice that occurred during my arbitration proceedings. This assertion was made on December 13, 1995, when he served as my initial arbitration appeal lawyer. Ten days later, on December 19, I provided Law Partners with comprehensive copies of the evidence I had previously presented to Darren Kearney, a representative from AUSTEL, the Australian telecommunications authority. Mr. Kearney undertook an extensive five-hour journey from Melbourne to my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, motivated by the importance of reviewing the same critical evidence that had led Mr. Volovich to express his concerns regarding the potential for an appeal.

The circumstances that precipitated this situation emerged when AUSTEL allowed Telstra, a major telecommunications provider, to address contentious billing documents on October 16, 1995. This decision was made outside the established arbitration process and occurred without my presence, as well as that of the arbitrator. Instead of providing accurate and transparent information in their written correspondence, Telstra opted to covertly misrepresent key facts related to my evidence, thereby undermining the integrity of the arbitration process. This prompted officials from AUSTEL to engage in both telephone conversations and written communication with me, inquiring whether they could examine my arbitration claim materials. Notably, these materials had not been subjected to thorough investigation or documented analysis by Dr. Gordon Hughes and his team of technical consultants, despite the explicit requirements set forth in the arbitration rules mandating their adherence by the arbitrator. AUSTEL had previously discussed this procedural violation in their COT Cases report of April 1994 and expressed astonishment that Dr. Hughes had chosen not to comply with these stipulations.

On December 19, after Mr. Kearney had meticulously examined the uninvestigated claim materials at my holiday camp, he respectfully requested permission to transport these documents back to Melbourne for further review. Faced with the gravity of the situation and the status of Mr. Kearney as a government official, it was difficult for me to decline such a request. Although Mr. Kearney provided me with assurances, both in a written format and in person, regarding the government's intent to furnish me with findings related to this outstanding arbitration claim material, I have yet to receive any such findings, leaving my claims unresolved.

As outlined in File 51G, addressed to Senator Ron Boswell from Michael Brereton & Co. lawyers and dated August 10, 1997, I possessed a substantive case against Dr. Hughes. However, despite the validity of my claims and the potential for legal recourse, I found myself unable to secure adequate legal representation or assistance from their office, exacerbating the challenges I faced in my pursuit of a just resolution.

It is important to note that during the first week of January 1994, the COTs advised Warwick Smith, the TIO, who was also the administrator of both the Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP) and the Fast Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP), that AUSTEL’s Chairman, Robin Davey, had also assured the COTs that Freehill’s would no longer be involved in their Fast Track Settlement Proposal. An internal Telstra email (FOI folio C02840) from Greg Newbold to various Telstra executives (AS 928) notes:

"Steve Lewis (Australian Financial Review news reporter) is following up on his own yarn NOT with the Davey letter to the minister but with the Davey letter to the CEO raising concerns about our use of Freehills."

Later, between January and March 1994, when the COTs again spoke to Warwick Smith concerned that Telstra had now appointed Freehills as their FTAP defence lawyers, the TIO’s response was that it was up to Telstra who they appointed as their arbitration lawyers, even though Alan also advised the TIO, in March 1994, that he was still having to register his phone complaints through Freehills and had still not been provided with any of the technical data to support Freehill’s assertions that there was nothing wrong with his telephone/fax service. This was a grave conflict of interest situation.

During and after my arbitration he raised his concerns that the arbitrator had not addressed Freehill’s submission of Telstra witness statements that had only been signed by Freehills and not by those who were actually making the statements. Nothing was transparently done to assist me in this matter other than to send this witness statement back to be signed by the alleged author making the statement.

My appeal lawyer (Law Partners of Melbourne) was not only staggered to learn about this witness statement issue, but was also staggered to learn that none of the arbitration fault correspondence that had been exchanged between Freehills, Telstra and I was ever provided to me as it should have been according to the rules of discovery. In fact, my lawyer suggested that perhaps Telstra had originally appointed Freehills to be my designated fault complaint managers so that any of that correspondence would form what Telstra believed to be a legal bridge, so that my ongoing telephone fault evidence could be concealed under Legal Professional Privilege (LPP) during his arbitration.

Telstra’s continued use of Freehills throughout the COT arbitrations and the arbitrator’s refusal, in my case, to look into why Telstra was withholding technical data under LPP, suggested, at the time, that the arbitrator was not properly qualified as he didn’t seem to understand that Telstra could not legally conceal technical information under LPP.

As this story reveals, Dr Hughes was, in fact, not a graded arbitrator at all, and was not registered as an arbitrator with the arbitrator’s umbrella organisation, then called the Institute of Arbitrators Australia.

19th October 1993: This document from Denise McBurnie (Freehill's) to Telstra's Don Pinel titled Legal Professional Privilege In Confidence FOI folio A06796: includes the following statements:

"Duesbury & FHP continuing of evaluating (blank) claim - final report to Telecom will be privileged and will not be made available to (blank).

Telecom preparing report for FHP analysing data available on (blank) services ie. (CCAS, Leopard, CABS and file notes) – this report will be privileged and will not be made available to (blank)." (AS 930)

In other words, Telstra FOI documents (folio R00524 and A06796) confirm Telstra were already hiding technical information from the COT claimants under Legal Professional Privilege. It is important to note here that Telstra had directed me to register my 'ongoing' telephone faults, in writing, to Denise McBurnie of Freehills in order to have those issues addressed. I found this not just time consuming, but also very frustrating, because by the time he received a response to one complaint he already had further complaints to register. It wasn’t until I entered the arbitration process that it appeared as though Telstra were using Freehills’ Legal Professional Privilege strategy to hide numerous important technical documents from the claimants, including the very same 008/1800 fault complaints that I had registered through Freehills, according to Telstra’s directions.

29th October 1993: this Telstra FOI document folio K01489 Exhibit (AS 767-A) notes

"During testing the Mitsubishi fax machine, some alarming patterns of behaviour were noted, these affecting both transmission and reception. Even on calls that were not tampered with the fax machine displayed signs of locking up and behaving in a manner not in accordance with the relevant CCITT Group 3 fax rules."

The hand-written note in the bottom right corner of Exhibit AS 767-B, which states: “Stored in Fax Stream?” suggests that faxes intercepted via Telstra’s testing process are stored in Telstra's Fax Stream service centre so the document can be read, at any time, by anyone with access to Telstra’s fax stream centre. The Scandrett & Associates report proves that numerous COT arbitration documentation was definitely intercepted, including faxes travelling to and from Parliament House, the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office (COO) and the COTs and, in my case at least, that this interception continued for seven years after his arbitration was over. This means, in turn, that Telstra had free access to in-confidence documents that the claimants believed they were sending ONLY to their accountants, lawyers and/or technical advisors (as well as Parliament House and the COO), and those documents could well have included information that the claimants might not have wanted disclosed to the defendants at the time

Was the engineer pressured to stay quiet during my arbitration? I don't know. Certainly, not all Telstra engineers or technicians treated COT complaints in good faith. Another Telstra technician, who experienced major problems during his official fax testing process on 29 October 1993, nevertheless advised the arbitrator that I had no problems with that service, even though the Telstra document that discusses these faults notes:

In a similar incident, an FOI document regarding a complaint I lodged about my own phone service bears a hand-written note which states: 'No need to investigate, spoke with Bruce, he said not to investigate also.'

Where was this attitude coming from? If from higher management, it seems an odd way to do business: exacerbating our problems so that we would only complain more.

In the first five months of 1993, I received another eleven written complaints, including letters from the Children's Hospital and the Prahran Secondary College in Melbourne. The faults had now plagued my business, unabated, from April 1988 to mid-1993.

By now, due to COT's pressure in Canberra, a number of politicians had become interested in our situation. The question was, would these politicians actually take any action on our behalf, or would they protect the 'milking cow' of the Telstra corporation?

In June 1993, the Shadow Minister for Communications, the Hon. Senator Richard Alston was showing an interest. He and Senator Ron Boswell of the National Party both pushed for a Senate Inquiry into our claims and, an ex-Telstra employee recently told me they were very close to pulling it off. If this Senate Inquiry had got off the ground, heads in Telstra might have rolled, but this didn't happen, and those same 'heads' continue to control Telstra to this day.

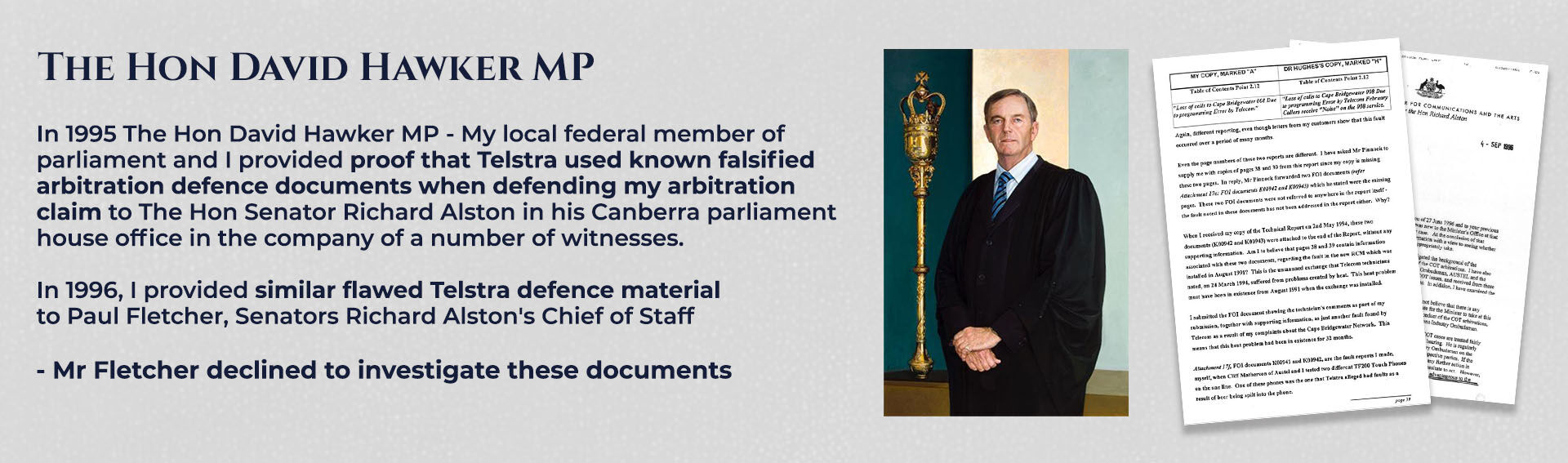

Even though Senator Boswell is based in Queensland and most of the remaining members of COT are in Victoria, he has continued to offer his support. David Hawker MP, my local parliamentary member, was another who saw his 'duty of care to his constituents and so answered our call for help. He took my claims seriously — indeed, he took the problem of poor phone service in his electorate seriously and was appalled at its extent. Mr Hawker sent me letters of support, put relevant people in touch with me, organised assistance for me, and has continued to go into battle on COT's behalf for ten years now.

Non-connecting calls

While the politicians tried to launch a Senate Enquiry, COT continued to lobby Austel for assistance. Yet another telephone issue was affecting my business. In February 1993, I installed an 1800 free call number to encourage telephone business and experienced problems right from the start. Many calls to this number were not connecting; the caller heard only silence on the line and typically hung up. The business was potentially losing a client, but adding insult to injury, I was charged for these non-connecting calls. Even worse, in many instances, the caller heard a recorded announcement from Telstra to the effect that the number wasn't connected. I first knew this problem was occurring through people reporting their difficulties trying to reach me. After this, I checked my bills carefully.

According to Telstra's policy, customers are charged only for calls that are answered. Unanswered calls are not charged and include:

… calls encountering engaged numbers (busy), various Telstra tones and recorded voice announcements as well as calls which 'ring out' or are terminated before or during ringing.

Between February and June 1993, I provided Austel with evidence of erroneous charging on unanswered calls on my 1800 service (in fact, it went on for at least another three years after that). John MacMahon, General Manager of Consumer Affairs at Austel, wanted a record of all non-connected calls and RVAs that were being charged to my 1800 account. In order to provide that, I needed the data from my local exchange.

Both Austel and the Commonwealth Ombudsman's Office were aware that I made repeated requests of Telstra, under the rules of FOI, to provide me with the relevant data. Yet, despite the involvement of these institutions, Telstra held out on me. In the end, it was more than a decade later that I received any of the relevant information, and that was through Austel. And, of course, it was too late by then. The statute of limitations on the matter had long expired.

I did not understand then, nor do I understand why Austel, as the government regulator of the telecommunications industry, could not demand that data from Telstra.

From June 1993, I had proof that Telstra knew the faulty billing in the 1800 system was a network problem from its inception.

The Briefcase

Ericsson AXE faulty telephone exchange equipment (1)

I should have known better. It was just another case of 'No fault found.' We spent some considerable time 'dancing around' a summary of my phone problems. Their best advice for me was to keep doing exactly what I had been doing since 1989, keeping a record of all my phone faults. I could have wept. Finally, they left.

A little while later, in my office, I found that Aladdin had left behind his treasures: the Briefcase Saga was about to unfold.

Aladdin

The briefcase was not locked, and I opened it to find out it belonged to Mr Macintosh. There was no phone number, so I was obliged to wait for business hours the next day to track him down. However, what there was in the briefcase was a file titled 'SMITH, CAPE BRIDGEWATER'. After five gruelling years fighting the evasive monolith of Telstra, being told various lies along the way, here was possibly the truth, from an inside perspective.

The first thing that rang alarm bells was a document that revealed Telstra knew that the RVA fault they recorded in March 1992 had actually lasted for at least eight months — not the three weeks that was the basis of their settlement payout. Dated 24/7/92, and with my phone number in the top right corner, the document referred to my complaint that people ringing me get an RVA' service disconnected' message with the 'latest report' dated 22/7/92 from Station Pier in Melbourne and a 'similar fault reported' on 17/03/92. The final sentence reads: 'Network investigation should have been brought in as fault has gone on for 8 months.'

I copied this and some other documents from the file on my fax machine and faxed copies to Graham Schorer. The next morning I telephoned the local Telstra office, and someone came out and picked the briefcase up.

The information in this document dated 24 July 1992 was proof that senior Telstra management had deceived and misled me during previous negotiations. It showed that their guarantees that my phone system was up to network standard were made in full knowledge that it was nowhere near 'up to standard'.

It is noted that Telstra's area general manager was fully aware at the time of my settlement on 11 December 1992 that she was providing me with incorrect information. This information had influenced my judgement of the situation, placing me at a commercial disadvantage, but the General Manager, Commercial Victoria/Tasmania, was also aware of this deception.

The use of misleading and deceptive conduct in a commercial settlement such as mine contravenes Section 52 of the Australian Trade Practices Act. Yet this deception has never been officially addressed by any regulatory body. To get ahead of my story here, even the arbitrator who handed down his award on my case in May 1995 failed to question Telstra's unethical behaviour.

Previously Withheld Documents

I took this new information to Austel and provided them several documents that had previously been withheld from me during my 11 December 1992 settlement which had been in the brifcase. On 9 June 1993, Austel's John MacMahon wrote to Telstra regarding my continuing phone faults after the settlement and the content of the briefcase documents:

Further he claims that the Telecom documents contain network investigation findings which are distinctly different from the advice which Telecom has given to the customers concerned.

In Summary, these allegations, if true, would suggest that in the context of the settlement, Mr Smith was provided with a misleading description of the situation as the basis for making his decision. They would also suggest that the other complainants identified in the folders have knowingly been provided with inaccurate information.

I ask for your urgent comment on these allegations. You are asked to immediately provide AUSTEL with a copy of all the documentation, which was apparently inadvertently left at Mr Smith's premises for its inspection. This, together with your comment, will enable me to arrive at an appropriate recommendation for AUSTEL's consideration of any action it should take.

As to Mr Smith's claimed continuing service difficulties, please provide a statement as to whether Telecom believes that Mr Smith has been provided with a telephone service of normal network standard since the settlement. If not, you are asked to detail the problems which Telecom knows to exist, indicate how far beyond network standards they are and identify the cause/causes of these problems.

In light of Mr Smith's claims of continuing service difficulties, I will be seeking to determine with you a mechanism that will allow an objective measurement of any such difficulties to be made.

I can only presume that Telstra did not comply with the request 'to immediately provide AUSTEL with a copy of all the available documentation which was apparently inadvertently left at Mr Smith's premises,' on 3 August 1993. Austel's General Manager, Consumer Affairs, wrote to Telstra requesting a copy of all the documents in this briefcase that had not already been forwarded to Austel.

I sent off a number of Statutory Declarations to Austel explaining what I had seen in the briefcase.Telstra had returned and picked up the briefcase.

One-third of documents which I managed to copy was enough information to convince AUSTEL that Ericsson and Telstra were fully aware the AXE Ericsson lock-up faults was a problem worldwide affecting 15 to 50 percent of all calles generate through this AXE exchange equipment. It was locking up flaws affected the billing software.

Thousands upon thousands of Telstra customers Australia wide had been wrongly billed since the instalation of this Ericsson AXE equipment which in my case, had been installed in August 1991, with the problems still apparent in 2002. Tther countries around the world were removing or had removed it from their exchanges (see File 10-B Evidence File No/10-A to 10-f ), and Australia was still denying to the arbitrator there was ever a problem with that equipment. Lies told by Telstra so as to minmize their liability to the COT Cases. (See Files 6 to 9 AXE Evidence File 1 to 9)

Was this the real reason why the Australian government allowed Ericsson to purchase Lane during the government endorsed COT arbitration while the arbitrations were still in progress?

When the COT arbitration documents submitted into arbitration proved that this Ericsson AXE lock-up call loss rate was between from 15% to 50% as File 10-B Evidence File No/10-A to 10-f so clearly shows. AUSTEL then instigated an investigation into these AXE exchange faults and uncovered some 120,000 COT-type complaints were being experienced around Australia. Exhibit (Introduction File No/8-A to 8-C), shows AUSTEL's Chairman Robin Davey received a letter from Telstra's Group General Manager (who was also Telstra's main arbitration defence liaison officer), suggesting he alter that finding for 120,000 COT-type complaints to show a hundred. If fact when the public AUSTEL COT Cases report was launched on 13 April 1994, it shown AUSTEL located up-wards of 50 or more COT-type complaints being experienced around Australia.

Was this the major problem Julian Assange wanted to share with the COT Cases? He said corruption was significant. How bigger could this have been had it been exposed during the COT arbitrations?

In my case, none of the relevant arbitration claims raised against Ericsson, whose official arbitration records numbered A56132, were investigated, including my Telstra's Falsified SVT Report. Why did Lane ignore this evidence against Ericsson?

Even worse was when my arbitration claim documents were returned to me after the conclusion of the arbitration NONE of my Ericsson technical data was amongst the returned material.

I believe the Australian government should answer the following questions: How long was Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd in contact with Ericsson, the major supplier of telecommunication equipment to Telstra before Ericsson purchased Lanes? Is there a link between Lanes ignoring my Ericsson AXE claim documents and the purchase of Lane by Ericsson during the COT arbitration process?

Is there a sinister link between the government communications media regulator ACMA denying me access to the Ericsson AXE documentation which I lawfully tried to gain access to during my two government Administrative Appeal Tribunal hearings in 2008 and 2011 (see Chapter 9 - The ninth remedy pursued and Chapter 12 - The twelfth remedy pursued).

The latest 2019/2020 5G Ericsson partnership with Telstra is relevant to all Australian Telstra subscribers; however, it is also relevant that the same subscribers if they were to visit this website absentjustice.com where you can see, yourself, that my claims against Telstra and Ericsson are valid (see Bribery and Corruption - Part 2).

Therefore, it is important to highlight the Ericsson here the bribery and corruption issues the US Department of Justice raised against Ericsson as discussed above in the Australian media reports on 19 December 2019

On 27 August 1993, Telstra's Corporate Secretary, Jim Holmes, wrote to me about the contents of the briefcase:

Although there is nothing in these documents to cause Telstra any concern in respect of your case, the documents remain Telstra's property. They, therefore, are confidential to us … I would appreciate it if you could return any documents from the briefcase still in your possession as soon as possible.

How blithely he omitted any reference to vital evidence which was withheld from me during their negotiations with me regarding compensation.

Flogging a dead horse

By the middle of 1993, people were becoming interested in what they heard about our battle. A number of articles had appeared in my local newspaper, and interstate gossip about the COT group was growing. In June, Julian Cress from Channel Nine's 'Sixty Minutes' faxed me:

Just a note to let you know that I had some trouble getting through to you on the phone last Thursday. Pretty ironic, considering that I was trying to contact you to discuss your phone problems.

The problem occurred at about 11 am. On the 008 number I heard a recorded message advising me that 008 was not available from my phone and your direct line was constantly engaged.

Pretty ironic, all right!

A special feature in the Melbourne Age gave my new 'Country Get-A-Ways' program a great write-up. It was marketing weekend holidays for over-40s singles in Victoria and South Australia: an outdoor canoe weekend, a walking and river cruise along the Glenelg River and a Saturday Dress-up Dinner Dance with a disco as well as a trip to the Coonawarra Wineries in South Australia with a Saturday morning shopping tour to Mt Gambier. I began to feel things were looking up for the Camp.

It was too much to hope for that my telephone saga was coming to an end. A fax arrived on the 26 October 1993, from Cathine, a relative of the Age journalist who wrote the feature:

Alan, I have been trying to call you since midday. I have rung seven times to get an engaged signal. It is now 2.45 pm.

Cathine had been ringing on my 1800 free-call line. I had been in my office and there had been no calls at all between 12.30 and 2.45 that day. What was going on? (Telstra's data for that day shows one call at 12:01, lasting for 6 minutes and another at 12:18, lasting for 8 minutes). I cannot express how frustrating this was; there seemed to be no end to it in sight. But I was determined not to let the bastards get me down. Their lies and incompetence had to be exposed. That day shows one call at 12:01, lasting for 6 minutes and another at 12:18, lasting for 8 minutes). I cannot express how frustrating this was; there seemed to be no end to it in sight. But I was determined not to let the bastards get me down. Their lies and incompetence had to be exposed.

I stepped up my marketing of the Camp and the singles weekends, with personal visits to social clubs around the Melbourne metropolitan area and in Ballarat and Warrnambool. I followed with ads in local newspapers in metropolitan areas around Melbourne and in many of the large regional centres around Victoria and South Australia. I also placed ads for the Get-Away holidays in the 1993 White Pages — or rather, I tried to: the entries never made it into the telephone books. I complained of this to the TIO (the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman), who attempted to extract from Telstra an explanation for my advertisements being left out of 18 major phone directories.

As the Deputy TIO said in his letter to me of 29/3/96, he believed his office would simply 'be flogging a dead horse trying to extract more' from Telstra on this matter. (In fact, the TIO is an industry body supervised by a board, the members of which are drawn from the leading communications companies in the country: Vodaphone, Optus and, of course, Telstra.)

Between May and October of 1993, in response to my request for feedback, I received many letters from schools, clubs and singles clubs, writing of the difficulties they had experienced trying to contact the Camp by phone. The executive officer of the Camping Association of Victoria, Mr Don MacDowall, wrote on 6 May 1993 to say that 10,000 copies of their Resource Guide, which I had advertised, had been directly mailed to schools and given away. Mr MacDowall had said the other advertisers with ads similar to mine had experienced an increase in inquiries and bookings after distributing these books. So it seemed evident to him that the 'malfunction of your phone system effectively deprived you of similar gains in business.' He also noted that he had himself received complaints from people asking why I was not answering my phone. All in all, during this period, I received 36 letters from different individuals as well more than 40 other complaints from people who had tried, unsuccessfully, to respond to my advertisements. The Hadden & District Community House wrote in April 1993:

Several times I have dialled 055 267 267 number and received no response — dead line. I have also experienced similar problems on your 008 number.

Our youth worker, Gladys Crittenden, experienced similar problems while organising our last year's family camp, over a six month period during 1991/1992.

In August 1993 Rita Espinoza from the Chilean Social Club wrote:

I tried to ring you in order to confirm our stay at your camp site. I found it impossible to get through. I tried to ring later but encountered the same signal on 10 August around 7 – 8.30 pm. I believe you have a problem with the exchange and strongly advise you contact Telstra.

Do you remember the same problem happened in April and May of this year?

I apologise but I have made arrangements with another camp.

A testing situation

Late in 1993, a Mrs Cullen from Daylesford Community House informed me that she had tried unsuccessfully to phone me on 17 August 1993 at 5.17, 5.18, 5.19 and 5.20 pm, each time reaching a deadline. She had reported the fault to Telstra's Fault Centre in Bendigo on 1100, speaking to an operator who identified herself as Tina. Tina then rang my 1800 number, and she couldn't get through either. Telstra's hand-written memo, dated 17 August 1993, records the times Mrs Cullen tried to get through to my phone and reports Tina's failed attempt to contact me.

A copy of my itemised 1800 account shows that I was charged for all four of these calls, even though Mrs Cullen never reached me. All this information was duly passed to John MacMahon of Austel and, soon afterwards, Telstra at last arranged for tests on my line. These were to be carried out from a number of different locations around Victoria and New South Wales. Telstra notified Austel that some 100 test calls would take place on 18 August 1993 to my 1800 free-call service.

First thing that morning I answered two calls from Telstra Commercial, one lasting six minutes and another lasting eleven minutes, as they set up in readiness for the test calls expected that day. Over the rest of that day, there were another eight, perhaps nine calls from Telstra, which I answered. My 1800 phone account arrived, showing more than 60 calls charged to my service some days later. I queried this with Telstra, asking first how I could be charged for so many calls which did not ring, and next, why I should be paying for test calls anyway. In hindsight, I should have asked how more than 60 calls could have been answered in just 54 minutes when the statement shows that some of these calls came through at the rate of as many as three a minute.

Telstra wrote to Austel's John MacMahon on 8 November 1993, informing him that I had acknowledged answering a 'large number of calls' and that all the evidence indicated that 'someone at the premises answered the calls.' Austel asked for the name of the Telstra employee who made these so-called successful calls to my business, and I have also asked for this information, but Telstra didn't respond.

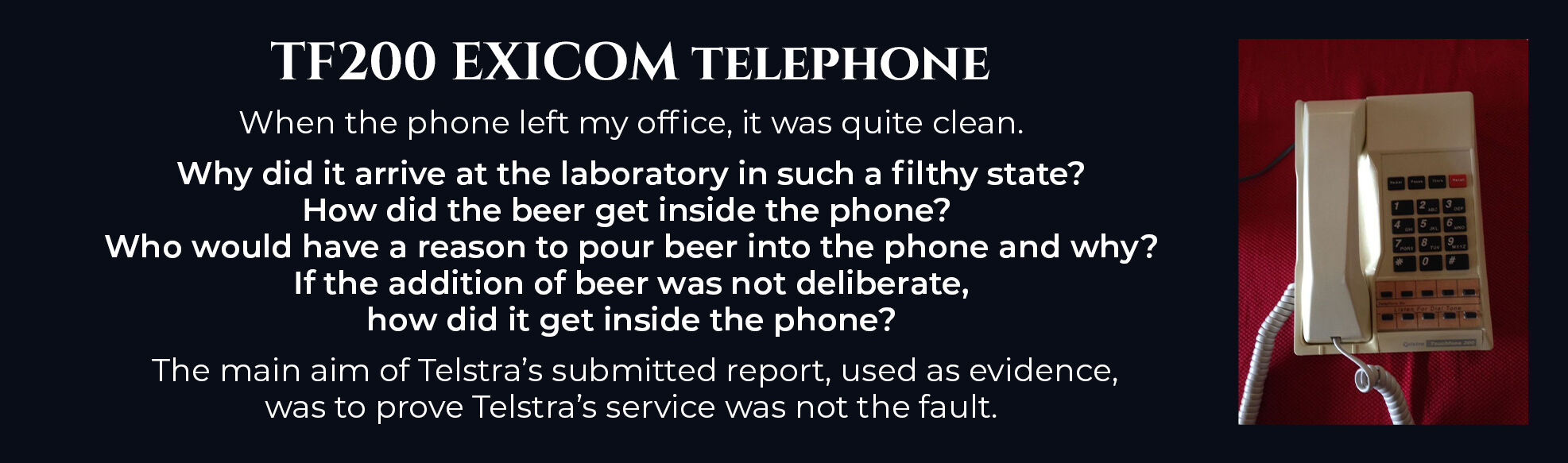

Then on 28 January 1994, I received a letter from Telstra's solicitors in which they referred to 'malicious call trace equipment' Telstra had placed — without my knowledge or consent — on my service between 26 May and 19 August 1993. This was the first I'd heard of it. This device, they explained, apparently caused a 90-second lock-up on my line after a call was answered, meaning that no further call could come into my phone for 90 seconds after I hung up.

This information put another complexity on the matter of those four calls from Mrs Cullen I was charged for in the space of a single 28 seconds and the 100 test calls from Telstra. Even supposing I could answer the phone at such a fast rate, the malicious call tracing equipment, apparently attached to my line at that time, was imposing its 90-second delay between calls, making the majority of these calls impossible. Telstra management, of course, had nothing to say about this.

What was going on? As far as I could tell, most of those 100 test calls simply weren't made; indeed, they couldn't have been made.

Late in 1994, I received two FOI documents concerning these calls. K03433 and K03434 showed 44 calls, numbered between 8 and 63, to the Cape Bridgewater exchange, nine of which had tick or arrow marks beside them. More than once, I asked Telstra what the marks represent but received no response. However, I presume that a technician made these marks against the calls I actually received and answered. A note on K03434 read:

Test calls unsuccessful. Did not hear STD pips on any calls to test no. The TCTDI would not work correctly on the CBWEX (Cape Bridgewater Exchange). I gave up tests.

The technicians themselves gave up on their testing procedure! The second series of tests conducted a year later in March 1994 fared little better. Telstra's fault data notes that only 50 out of 100 test calls were successfully connected. This information was of no use to me at the time, however, as it was withheld from me until September 1997. All I was to hear in 1994 was the old refrain: 'No fault found.'

Only one official document drew attention to the incapacity of Telstra's testing regime, and this was the Austel Draft Report regarding the COT cases, dated 3 March 1994, which concluded:

Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of services difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991, it is apparent that the Camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years, which has impacted on its business operations, causing losses and erosion of the customer base.

In view of the continuing nature of the fault reports and the level of testing undertaken by Telecom doubts are raised on the capability of the testing regime to locate the causes of faults being reported.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995 noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report., should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

It is also clear from Exhibit 8 dated 11 August 1995 (see BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46 a letter from BCI to Telstra;s Steve Black and Exhibit 36 on (see BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46 a further letter from BCI to Telstra's John Armstrong that neither letter is on a BCI letter head, as are Exhibits 1 to 7, from BCI to Telstra (see BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46.

Both Exhibits 8 and 36 were provided by Telstra to the Senate Committee in October 1997, to support that BCI Cape Bridgewater tests were genuine when the evidence on absentjustice.com and Telstra's Falsified BCI Report confirms it is not.

Telstra has been relying on government ministers to ignore this fraud which the government has done for the past two decades or more.

As far as Telstra's Simone Semmens stating on Nationwide TV (see above) that the Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) test conducted at the COT Cases telephone exchanges that serviced their business proved there were no systemic billing problems in Telstra's network does not coincide with the evidence attached to my website absentjustice.com or the public statement made by Frank Blount. The latter was Telstra's CEO during my arbitration. In 2000 in his co-produced manuscript.

On pages 132 and 133 in publication Managing in Australia (See File 122-i - CAV Exhibit 92 to 127) Frank Blounts reveaks Telstra did have a systemic 1800 billing problem affecting Australian consumers accross Australia. These were the same 1800 billing problems the arbitrator Dr Gordon Hughes would not allow his two technical consultants DMR (Canada) and Lane (Australia) to investigate (see Chapter 1 - The collusion continues).

Had Dr Hughes given DMR & Lane the extra weeks they stated in their 30 April 1995 report was needed to investigate these ongoing 1800 faults (see Chapter 1 - The collusion continues) DMR & Lane would have uncovered what Frank Blount had uncovered. For Telstra to have mislead and deceivied the arbitrator concerning these 1800 faults is one thing, but to mislead and devieve their 1800 customers is another issue in deed.

The following link Evidence - C A V Part 1, 2 and 3 -Chapter 4 - Fast Track Arbitration Procedure confirms Frank Blount, Telstra’s CEO, after leaving Telstra in he co-published a manuscript in 2. entitled, Managing in Australia. On pages 132 and 133, when discussing these 1800 network faults the author/editor writes exposes :

- “Blount was shocked, but his anxiety level continued to rise when he discovered this wasn’t an isolated problem.

- The picture that emerged made it crystal clear that performance was sub-standard.” (See File 122-i - CAV Exhibit 92 to 127)

Frank Blount's Managing Australia https://www.qbd.com.au › managing-in-australia › can still be purchased online.

The fact that Telstra allowed Simone Semmens to state on Nationwide TV that the Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) test proved there were no systemic billing problems in Telstra's network during the four years of the COT arbitrations is bad enough, but to have said it when there were other legal processes being administered where the billing was an issue is deception of the worse possible kind, especially after Senator Schacht, advised Telstra's Mr Benjamin of his concerns regarding Simone Semmen's statement inferring Telstra's network was of world statdard when both Telstra and BCI knew different.

Telstra’s Mr Benjamin's statement to Senator Schacht — "...I am not aware of that particular statement by Simone Semmens, but I think that would be a reasonable conclusion from the Bell Canada report,'' is also misleading and deceptive because I had already provided Mr Bejamin (see AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233 - AS-CAV 196, AS-CAV 188, AS-CAV 189 and AS-CAV 190-A), with the proof the Cape Bridgewater BCI tests were fundamentally flawed.

Senator Schacht' s further statement — since then of course—not in conversations but elsewhere— we now have major litigation running into hundreds of millions of dollars between various service providers and so on which are complaints about the billing system. Does that indicate that she may have been partly wrong?

Wrong or not, we know that several of those business owners who made those complaints lost their court actions and their businesses.

FIVE YEARS ON

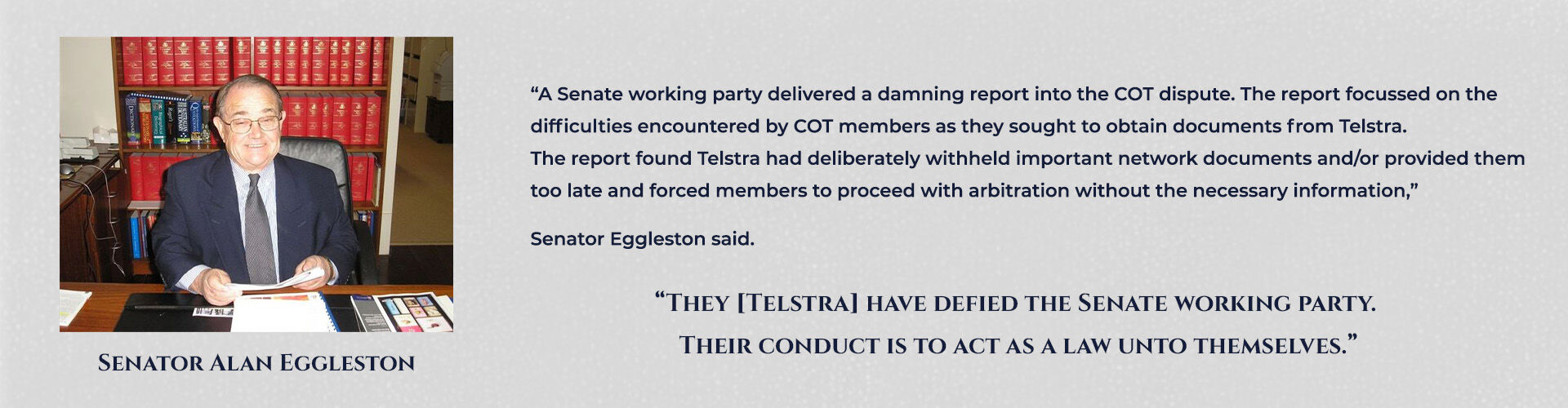

Telstra in contempt of the Senate

On 23 March 1999, almost five years after most of the arbitrations had been concluded, the Australian Financial Review (newspaper) reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why the COT Cases were forced into a government-endorsed arbitration without the necessary documents they needed to fully support their claims i.e.

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focussed on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

I doubt there are many countries in the Western world governed by the rule of law, as Australia purports to be, that would allow a group of small-business operators to be forced to proceed with a government-endorsed arbitration while allowing the defence (the government which owned the corporation) to conceal the necessary documents these civilians needed to support their claims. Three of those previously withheld documents confirm Telstra was fully aware that the Cape Bridgewater Bell Canada Internations Inc (BCI) tests could not possibly have taken place according to the official BCI report Telstra used as arbitration defence documents.

On my behalf, Mr Schorer (COT. Spokesperson) raised the Cape Bridgewater BCI deficient tests with Senators Ron Boswell and Chris Schacht. Pages 108-9 of Senate Hansard records (refer to Scrooge - exhibit 35) confirm Telstra deflected the issue of impracticable tests by stating my claim – that the report was fabricated – was incorrect. The only problem with the report was an incorrect date for one of the tests. The Senate then put Telstra on notice to provide evidence of that error.

If the 12 January 1998 letter to Sue Laver, with the false BCI information attached is not enough evidence to convince the Australian Government that Telstra cannot continue pretending. They know nothing about the falsified Cape Bridgewater BCI tests, Telstra, and the Senate estimates committee chair was again notified, on 14 April 1998, that the Cape Bridgewater BCI tests were impracticable. When is Telstra going to come forward and advise the Telstra board that my claims are right and that indeed it was unlawful to use the Cape Bridgewater BCI tests as arbitration defence documents as well as grossly unethical to have provided the Senate with this known false information when answering questions on notice?

On pages 23-8 of this letter, and using the Cape Bridgewater statistics material, Graham provided clear evidence to Sue Laver and the chair of the Senate legislation committee that the information Telstra provided to questions raised by the Senate on notice, in September and October 1997, was false (see Scrooge - exhibit 62-Part One and exhibit 62-Part-Two). Telstra was in contempt of the Senate. No one yet within Telstra has been brought to account for supplying false Cape Bridgewater BCI results to the Senate. Had Telstra not supplied this false information to the Senate, the Senate would have addressed all the BCI matters I now raise on absentjustice.com in 2021.

Telstra’s Falsified BCI Report’ is all the evidence necessary to show that arbitration lawyers provided false information to Telstra’s arbitration witness, namely the clinical psychologist, during my government-endorsed arbitration, and two years later, Telstra supplied that same BCI false information on notice to the Senate.

It is ironic that two Telstra technicians, in two separate witness statements dated 8 and 12 December 1994, discuss the testing equipment used by Telstra in overall maintenance and state that the nearest telephone exchange, to Portland and Cape Bridgewater, that could facilitate the TEKELEC CCS7 equipment was in Warrnambool 110 kilometres from Portland/Cape Bridgewater, where BCI alleged they carried out their PORTLAND / Cape Bridgewater tests via the Ericsson AXE exchanges trunked through the TEKELEC CCS7 equipment.

I have shown throughout this webpage absentjustice.com, including in the Brief Ericsson Introduction⟶ that in several cases such as Cape Bridgewater (where I tried to run my telephone dependent business), Ericsson telephone equipment was known to affect the telephone equipment that serviced my business. And yet Telstra was still prepared the lie and cheat in the arbitration defence of my claim as well as during a Senate Estimates investigation into my Ericsson AXE BCI claims.

On 12 January 1998, during the Senate estimates committee investigations into COT FOI issues, Graham Schorer provided Sue Laver (now in 2021) Telstra’s corporate secretary with several documents. On page 12 of his letter, Graham states:

“Enclosed are the 168 listings extracted from Telstra’s Directory of Network Products and Network Operations, plus CoT’s written explanation, which alleges to prove that parts of the November 1993 Bell Canada International The report is fabricated or falsified.”

Had the Senate been advised by Sue Laver there was merit in my complaints concerning the flawed BCI testing, my matters raised on absentjustice.com could have been resolved two decades ago.

Please click on the following link Telstra’s Falsified BCI Report and form your own opinion as to the authenticity of the BCI report which was used by Telstra as an arbitration defence document?

The evidence which supports the report is attached as BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46

On 23 October 1997, the office of Senator Schacht, Shadow Minister for Communications, faxed Senator Ron Boswell the proposed terms of reference for the Senate working party for their investigation into the COT arbitration FOI issues which Sue Laver,. Telstra's current Corporate Secretary in 2001, was heavily involved in these Senate hearings on behalf of Telstra. This document shows the two lists of unresolved COT cases with FOI issues to be investigated. My name appears on the Schedule B list (see Arbitrator File No 67). Telstra, by still refusing to supply these 16 COT cases with promised discovery documents, first requested four years earlier, was acting outside of the rule of law and yet, regardless of Telstra breaking the law, these 16 claimants received no help from the police, arbitrator or government bureaucrats and were denied access to their documents, as absentjustice.com shows.

Exhibit 20-A, a letter dated 9 December 1993 from Cliff Mathieson of AUSTEL to Telstra’s Manager of Business Commercial, states on page 3,

"...In summary, having regard to the above, I am of the opinion that the BCI report should not be made available to the assessor(s) nominated for the COT Cases without a copy of this letter being attached to it."

Had this letter and the many other letters in BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46 been provided to the senate as part of Telstra's response to questions placed on notice concerning my claims the BCI Cape Bridgewater tests were impracticable the Senate might well have demanded more information regarding my claims. This BCI 9 December 1993 letter is also discussed in the introduction to My story-warts and all as follows:

After my arbitration was concluded, I alerted Mr Tuckwell that Telstra had used these known corrupt Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) Cape Bridgewater tests to support their arbitration defence my claims without AUSTEL's letter being supplied to the arbitrator (see Telstra's Falsified BCI Report).

“The tests to which you refer were neither arranged nor carried out by AUSTEL. Questions relating to the conduct of the test should be referred to those who carried them out or claim to have carried them out.” File 186 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233

If Neil Tuckwell (on behalf of the government communications regulator) had demanded answers back in 1995 as to why Telstra used known falsified BCI tests, this falsifying of arbitration defence documents would have been dealt with in 1995 instead of still actively being covered up in 2022.

I reiterate, by clicking onto the following link Telstra’s Falsified BCI Report you can form your own opinion as to the authenticity of the BCI report and/or my version that clearly shows the Cape Bridgewater test was impracticable.

The evidence (46 exhibits) which support my report is attached as BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46

COT is partly vindicated by audit

For all its faults, Austel pressured Telstra to commission an audit of its fault handling procedures. Telstra engaged the international audit company of Coopers & Lybrand to report on its dealings with complaints like those raised by COT members. Coopers & Lybrand’s report conveys serious concern at the evidence we presented of Telstra’s unethical management of our complaints.

The Coopers report did not go down well with Telstra. The Group Managing Director of Telstra wrote to the Commercial Manager Refer to Chapter 6 Bad Bureaucrats:

… it should be pointed out to Coopers and Lybrand that unless this report is withdrawn and revised, that their future in relation to Telstra may be irreparably damaged.

These are strong words from the most senior manager below the CEO of a corporation that had a monopoly on the telecommunications industry in Australia. Austel tabled the Coopers & Lybrand report in the Senate, but with some significant changes to what had appeared in the draft report. Regardless of those changes, Coopers were still damning in their assessment to what had happened to the COT Cases.

The following points are taken directly from the Coopers & Lybrand report:

2.20 Some customers were put under a degree of pressure to agree to sign settlements which, in our view, goes beyond normal accepted fair commercial practices.

2.22 Telstra placed an unreasonable burden on difficult network fault cases to provide evidence to substantiate claims where all telephone fault information that could reasonably determine loss should have been held by Telstra.

(2) Fault handling procedures were deficient in terms of escalation criteria and procedures, and there is evidence that in some cases at least, this delayed resolution of these cases.

3.5 We could find no evidence that faults discovered by Telstra staff which could affect customers are communicated to the staff at business service centres who have responsibility for responding to customers’ fault reports.

We COT four at last felt vindicated; we were no longer alone in claiming that Telstra really did have a case to answer.

A Fast Track (Commercial Assessment) Settlement Process

To summarise. Senators Alston and Boswell had taken up COT’s cases with Telstra and Austel in August 1993, saying that if they were not swiftly resolved there would be a full Senate Inquiry. Telstra agreed to cooperate, and Austel was authorised to make an official investigation into our claims.

As a result of their investigation, Austel concluded that there were indeed problems in the Telstra network and that the COT four had been diligent in bringing these issues into the public domain. It looked like four Australian citizens, without any financial backing, had won a significant battle. Sometimes, we thought, David wins over Goliath, even in the twentieth century.

Because we were all in such difficult financial positions, Austel’s chairman, Robin Davey, recommended that Telstra appoint a commercial loss assessor to arrive at a value for our claims. These claims had already been found generally to be valid in Austel’s Report, The COT Cases: Austel’s Findings and Recommendations, April 1994 (public report) and it only remained for an assessor to determine an appropriate settlement based on the detailed quantification of our losses.

This ‘Fast Track Settlement Process’ was to be run on strictly non-legal lines. This meant we were not to be burdened with providing proof to support all of our assumptions, and we would be given the benefit of the doubt in quantifying our losses. This was the process Austel specifically deemed appropriate to our cases. Telstra was to give us prompt and speedy access to any discovery documents we needed to enable us to complete our claims as quickly as possible.

Telstra also agreed that any phone faults would be rectified before the assessor handed down any decision regarding payouts. After all, what good would a commercial settlement be if the phone faults continued? At last we began to feel we were getting somewhere. Robin Davey also assured us that any costs we might incur in preparing our claims would be considered as part of our losses, so long as our claims were proved. However, he would not confirm this assurance in writing because, he explained, it could set an unwanted precedent.

Telstra was anxious about setting precedents. On 18 November 1993, Telstra’s Corporate Secretary had written to Mr Davey pointing out that:

… only the COT four are to be commercially assessed by an assessor.

For the sake of convenience I have enclosed an amended copy of the Fast Track Proposal which includes all amendments.

To facilitate its acceptance by all or any of the COT members I have signed it on behalf of the company. Please note that the offer of settlement by this means is open for acceptance until 5 pm Tuesday 23 November 1993 at which time it will lapse and be replaced by the arbitration process we expect to apply to all carriers following Austel recommendations flowing from this and other reviews.

In effect, we four COT members were given special treatment in terms of having a commercial assessment rather than the arbitration process. By this time Austel was dealing with another dozen or so COT cases. We four were being ‘rewarded’ for the efforts we had made over such a long period of suffering business losses. On the other hand, we were also being pressured by this rush — we would lose the option for a commercial assessment if we didn’t sign by 23 November, a mere five days away. The problem was, we were reliant on the supporting documents we needed for our claims. For these we were dependent on Telstra’s good will, and their track record gave us no confidence in that. We were also concerned about the lack of written assurance regarding compensation for preparational and other expenses.

On 22 November we turned for advice to Senator Alston, Shadow Minister for Communications. His secretary, Fiona, sent him an internal memo headed ‘Fast Track Proposal’, in which she conveyed our concerns:

Garms and Schorer want losses in Clause 2(c) to include its definition, ‘consequential loss arising from faults or problems’ although Davey verbally claims that consequential losses is implied in the word ‘losses’ of which he has given a verbal guarantee he will not commit this guarantee to writing.

COT members are sceptical of Davey’s guarantee given that he will not commit it to writing. On top of this, COT alleges that Telstra, in the past, has not honoured its verbal guarantees and so does not completely trust Davey.

COT want your advice whether or not COT should demand that clause 2(c) include a broader definition of losses to include consequential losses.

COT was hoping for your advice by tomorrow.

There was no response from Senator Alston.

Graham, Ann, Maureen and I signed the FTSP the following day, hoping we could trust Robin Davey’s verbal assurances that consequential losses would be included and that Telstra would abide by their agreement to provide the necessary documents. I included a letter with the agreement, clearly putting my expectations of the process:

In signing and returning this proposal to you I am relying on the assurances of Robin Davey, Chairman of Austel, and John MacMahon, General Manager of Consumer Affairs, Austel, that this is a fair document. I was disappointed that Mr Davey was unwilling to put his assurances in writing, but am nevertheless prepared to accept what he said.

I would not sign this agreement if I thought it prevented me from continuing my efforts to have a satisfactory service for my business. It is a clear understanding that nothing in this agreement prevents me from continuing to seek a satisfactory telephone service.

Despite nagging doubts, we felt a great sense of relief once we had sent off the agreement. The pressure on all four of us had been immense with TV and newspaper interviews as well as our ongoing canvassing of the Senate. And I had never stopped hammering for change in rural telephone services, at least in Victoria.

In December 1993 David Hawker MP, my local federal member, wrote to congratulate me for my ‘persistence to bring about improvements to Telecom’s country services’ and regretted ‘that it was at such a high personal cost.’

This was very affirming, as was a letter from the Hon. David Beddall MP, Minister for Communications in the Labor Government, which said, in part:

Let me say that the Government is most concerned at allegations that Telecom has not been maintaining telecommunications service quality at appropriate levels. I accept that in a number of cases, including Mr Smith’s, there has been great personal and financial distress. This is of great concern to me and a full investigation of the facts is clearly warranted.

A number of other small businesses in rural Australia had begun to write to me regarding their experiences of poor service from Telstra detailing problems with their phones and various billing issues. I contacted Telstra management myself on a number of occasions, putting on record my requests for these matters to be resolved. I believe this was a responsible reaction to the letters I was receiving.

Rural subscribers wrote to TV stations and newspapers supporting my allegations that, with regard to telephone services, rural small-business people and the general public suffered a very bumpy playing field compared to our city cousins. David M. Thomson & Associates, Insurance Loss Adjusters in Ballarat, wrote to the producer of Channel 7’s ‘Real Life’, a current affairs program:

I have watched with interest the shorts leading up to tonight’s program as I have similar problems to the man at Cape Bridgewater.

Our office is located in Ballarat and due to Telstra structure the majority of our local calls are STD-fee based.

On many occasions we have been unable to get through to numbers we have dialled, often receiving the message ‘This number is not connected’ or similar messages which we know to be untrue.

Clients report that they often receive the engaged signal when calling us and a review of the office reveals that at least one of our lines was free at the relevant time.

We have just received our latest Telstra bill which in total is up about 25–30% on the last bill. This is odd because our work load in the billing period was down by about 25% and we have one staff member less than the previous billing period.

A letter to the Editor of Melbourne’s Herald-Sun, read:

I am writing in reference to your article in last Friday’s Herald-Sun (2nd April 1993) about phone difficulties experienced by businesses.

I wish to confirm that I have had problems trying to contact Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp over the past 2 years.

I also experienced problems while trying to organise our family camp for September this year. On numerous occasions I have rung from both this business number 053 424 675 and also my home number and received no response – a dead line.

I rang around the end of February (1993) and twice was subjected to a piercing noise similar to a fax. I reported this incident to Telstra who got the same noise when testing.

(Because of a number of reports regarding this ‘piercing noise’, Ray Morris from Telstra’s Country Division arranged to have my service switched to another system. Unfortunately this did not help.)

TV stations reported that their phones ran hot whenever they aired stories about phone faults. People rang from all over the country with complaints about Telstra’s service. This support from the media and the general public boosted our morale and gave us more energy to keep going as a group. We continued to push to have these matters addressed in the Senate.

AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, at points 10 to 212 were compiled after the government communications regulator investigated my ongoing telephone problems. Government records (see Absentjustice-Introduction File 495 to 551) show AUSTEL’s adverse findings were provided to Telstra (the defendants) one month before Telstra and I signed our arbitration agreement. This allowed Telstra the chance to conceal the documents AUSTEL had located in Telstra's files before my arbitration began. I did not get a copy of these same findings until 23 November 2007, 12 years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

Point 115 –

“Some problems with incorrectly coded data seem to have existed for a considerable period of time. In July 1993 Mr Smith reported a problem with payphones dropping out on answer to calls made utilising his 008 number. Telecom diagnosed the problem as being to “Due to incorrect data in AXE 1004, CC-1. Fault repaired by Ballarat OSC 8/7/93, The original deadline for the data to be changed was June 14th 1991. Mr Smith’s complaint led to the identification of a problem which had existed for two years.”

Point 130 –

“On April 1993 Mr Smith wrote to AUSTEL and referred to the absent resolution of the Answer NO Voice problem on his service. Mr Smith maintained that it was only his constant complaints that had led Telecom to uncover this condition affecting his service, which he maintained he had been informed was caused by “increased customer traffic through the exchange.” On the evidence available to AUSTEL it appears that it was Mr Smith’s persistence which led to the uncovering and resolving of his problem – to the benefit of all subscribers in his area”.

Point 153 –

“A feature of the RCM system is that when a system goes “down” the system is also capable of automatically returning back to service. As quoted above, normally when the system goes “down” an alarm would have been generated at the Portland exchange, alerting local staff to a problem in the network. This would not have occurred in the case of the Cape Bridgewater RCM however, as the alarms had not been programmed. It was some 18 months after the RCM was put into operation that the fact the alarms were not programmed was discovered. In normal circumstances the failure to program the alarms would have been deficient, but in the case of the ongoing complaints from Mr Smith and other subscribers in the area the failure to program these alarms or determine whether they were programmed is almost inconceivable.”

Spoliation of evidence – Wikipedia

In simple terms, by AUSTEL only providing Telstra with a copy of their AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings in March 1994, not only assisted Telstra during their defence of my 1994/95 arbitration it also assisted Telstra in 2006, when the government could only assess my claims on a sanitized report prepared by AUSTEL and not their AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

Muzzling the media

We were getting a good amount of media coverage, even though it appears likely that some journalists were being asked by Telstra to ‘kill’ certain stories.

A memo between executives within Telstra back in July, entitled ‘COT Cases Latest ’, states, in part:

I disagree with raising the issue of the courts. That carried an implied threat not only to COT cases but to all customers that they will end up as lawyer fodder. Certainly that can be a message to give face to face to customers to hold in reserve if the complainants remain vexatious.

We are left to wonder how many Telstra’s customers like the COT Cases, who once they went into arbitration and/or mediation, ended up as lawyer fodder with broken homes and businesses destroyed?

A TV news program was also a target:

Good news re Channel —— News. Haven’t checked all outlets but as it didn’t run on the main bulletin last night, we can be pretty certain that the story died the death. I wish I could figure which phrase it was that convinced —— not to proceed. Might have been one of ‘(name deleted) pearls.

The name deleted was Telstra’s Corporate Secretary at the time. I have omitted the identity of the TV station and reporter. We too can only wonder what it was that convinced a respected journalist to drop a story.

It transpired that the same area general manager who deliberately misinformed me during the settlement process in 1992–93 was one of the two Telstra staff appointed to ‘deal with the media/politicians’ regarding COT issues. Would she misinform the media the way she misinformed me, I wondered.

A memo between executives within Telstra back in July1993, entitled ‘Cot Wrap-Up’, states, in part:

I think it should be acknowledged these customers are not going to become delighted. We are dealing with the long-term aggrieved and they will not lie down.

Further, I propose that we consider immediately targeting key reporters in the major papers and turn them on to some sexy ‘Look at superbly built and maintained network’ stories.

I advise that Clinton be targeted for some decent Telstra exclusive stories to get his mind out of the gutter. Prologue Evidence File No 24 to 39

We ‘long-term aggrieved’ are left to wonder just who ‘Clinton’ was and why his mind was considered to be in the gutter.

Another most startling document which I received long after my arbitration Telstra FOI folio 101072 to 10123 titled “In-Service Test Performance for The Telecom Australia Public Switched Telephone Service (Telecom Confidential) notes:

“The performances tabulated below have been formulated to aid dispute investigation and resolution. The information contained herein is for internal Telstra Corporation use only and must not be released to any third party, particularly AUSTEL.” (refer 101072 Arbitrator File No 63)

If AUSTEL had known that this document included the words: “must not be released to any third party, particularly AUSTEL”, perhaps their public servants might not have perjured themselves in defence of Telstra’s arbitration claims that all the Service Verification Testing at my business on 29 September 1994 had met all AUSTEL’s specifications? And I believe those public servants certainly did perjure themselves, not only in their 2 February 1995 letter but again in the third COT cases quarterly report to the communications minister, the Hon Michael Lee MP. Refer to Main Evidence File No/2 and File No 3 which confirms that, at my premises at least, Telstra definitely did not carry out their arbitration Service Verification Testing (SVT) to AUSTEL’s mandatory specifications, at all.

During this story as well as on my website, I have raised the issue of the government communications regulator writing to Telstra before the COT arbitrations began to warn them that the government would be quite concerned if a certain legal firm had any further involvement with the COT settlement/arbitration process. I also raised my concern when the arbitration agreement faxed to the TIO’s office on 10 January 1994 bore the abbreviated name of this very same legal firm, despite the government assuring us this firm would NOT have a continuing role to play.

This FOI document (refer to Arbitrator File No/80), dated in the month of September 1993, was released to me by Telstra under FOI too late for me to use in my arbitration claim may well have persuaded the arbitrator to have allowed me more time to access documents from Telstra. As this document was released to me after my arbitration, one would have to assume it relates to my ongoing telephone problems i.e.

“All technical reports that relate to the customer’s service are to be headed “Legal Professional Privilege”, addressed to the Corporate Solicitor and forwarded through the dispute manager.”

This Legal Professional Privilege document must be related to the threats I received from Telstra that if I did not register my phone complaints with these same lawyers (in writing) then Telstra would not investigate those complaints.

Chapter 5

Sold out

TIO Evidence File No 3-A is an internal Telstra email (FOI folio A05993) dated 10 November 1993, from Chris Vonwiller to Telstra’s corporate secretary Jim Holmes, CEO Frank Blount, group general manager of commercial Ian Campbell and other important members of the then-government owned corporation. The subject is Warwick Smith – COT cases and it is marked as CONFIDENTIAL:

“Warwick Smith contacted me in confidence to brief me on discussions he has had in the last two days with a senior member of the parliamentary National Party in relation to Senator Boswell’s call for a Senate Inquiry into COT Cases.

“Advice from Warwick is:

Boswell has not yet taken the trouble to raise the COT Cases issue in the Party Room.

Any proposal to call for a Senate inquiry would require, firstly, endorsement in the Party Room and, secondly, approval by the Shadow Cabinet. …

The intermediary will raise the matter with Boswell, and suggest that Boswell discuss the issue with Warwick. The TIO sees no merit in a Senate Inquiry.“He has undertaken to keep me informed, and confirmed his view that Senator Alston will not be pressing a Senate Inquiry, at least until after the AUSTEL report is tabled.

“Could you please protect this information as confidential.”

Exhibit TIO Evidence File No 3-A confirms that two weeks before the TIO was officially appointed as the administrator of the Fast Track Settlement Proposal FTSP, which became the Fast-Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP) he was providing the soon-to-be defendants (Telstra) of that process with privileged, government party room information about the COT cases. Not only did the TIO breach his duty of care to the COT claimants, he appears to have also compromised his own future position as the official independent administrator of the process.

It is highly likely the advice the TIO gave to Telstra’s senior executive, in confidence, (that Senator Ron Boswell’s National Party Room was not keen on holding a Senate enquiry) later prompted Telstra to have the FTSP non-legalistic commercial assessment process turned into Telstra’s preferred legalistic arbitration procedure, because they now had inside government privileged information: there was no longer a major threat of a Senate enquiry.

Was this secret government party-room information passed on to Telstra by the administrator to our arbitrations have anything to do with the Child Sexual Abuse and the cover-up of the paedophile activities by a former Senator who had been dealing with the four COT Cases? The fact that Warwick Smith, the soon-be administrator of the COT settlement/arbitrations, provided confidential government in-house information to the defendants (Telstra) was a very serious matter.

On 17 January 1994, Warwick Smith the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) distributed a media release announcing that DR Gordon Hughes would be the assessor to the four COT Fast Track Settlements processes. The TIO did not say that, as I had feared, Telstra was not abiding by their agreement: they were not supplying us with the discovery documents critical for establishing our cases. The TIO also failed to tell the Australian public in this media release that he had agreed to secretly assist Telstra by providing them COT Cases issue that were being discussed in the Coalition government Party Room.

Telstra and the TIO was treating us with sheer contempt, and in full view of the TIO and assessor. We were beginning to believe that no single person, and no organisation, anywhere in Australia, had the courage to instigate a judicial inquiry into the way Telstra steamrolled their way over legal process.

To be fair, Austel’s chairman, Robin Davey, expressed his anger to Telstra about their failure to supply us our necessary documents, but it was to no avail. By February 1994, Senator Ron Boswell asked Telstra questions in the Senate, again to no practical avail. (Questions about this failure to supply FOI documents were raised in the Senate on a number of occasions over the following years, by various Senators, whose persistence ultimately paid off for some members of COT but, unfortunately, not for me.)

Worse than this, however, was a new problem for us COT four. The assessor had somehow been persuaded (presumably by Telstra) to drop the commercial assessment process he had been engaged to conduct and adopt instead an arbitration procedure based on Telstra’s arbitration process. Such a procedure would never be ‘fast-tracked, and was bound to become legalistic and drawn out. Telstra knew none of us had the finances to go up against its high-powered legal team in such a process. This was the last thing we COT members wanted. We had signed up for a commercial assessment and that’s what we wanted.

Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) telephoned the TIO, to explain why the COT four were rejecting the arbitration process. Our reasons were dismissed. The TIO said he had been spending too much time on his role as administrator of our FTSP; that his office had already incurred considerable expense because of this role (Telstra was slow in reimbursing those expenses). He went onto say that his office had no intention of continuing to incur expenses on our behalf. He told Graham that if we did not agree to drop our commercial agreement with Telstra, Telstra would pull out all stops to force us into a position where we would have to take Telstra to court to resolve our commercial losses.

Moreover, if we decided to take legal action to compel Telstra to honour their original commercial assessment agreement, he (the TIO) would resign as administrator to the procedure. This action, he insisted, would have forced an end to the FTSP and left us with no alternative but to each take conventional legal action to resolve our claims.

On 30 November 1993, this Telstra internal memo FOI document folio D01248, from Ted Benjamin, Telstra’s Group Manager – Customer Affairs and TIO Council Member writes to Ian Campbell, Customer Projects Executive Office. Subject: TIO AND COT. This was written seven days after Alan had signed the TIO-administered Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP). In this memo, Mr Benjamin states: