Chapter 1 - Can We Fix The CAN

(see Bad Bureaucrats File No/11 – Part One and File No/11 – Part Two)

Copper Wire was not compatible

The Hon David Hawker MP, who was also the Speaker in the House of Representatives in the John Howard government, was aware of just how bad the Ericsson AXE Portland telephone exchange problems and corroding copper-wire network (CAN) was in his electorate, at least between 1993 and 2006. In fact, he worked with me throughout this very difficult period, including convening a number of meetings locally and in Parliament House in Canberra between 1994 and 2006, in order to provide regular updates to the government regarding the CAN and Ericsson AXE telephone exchange problems constituents in his electorate were experiencing. The Liberal National Party and the government communications regulator cannot deny they knew exactly how bad the CAN and Portland AXE exchange problems were between 1993 and 2011, particularly as I alerted the Australian Communication and Media Authority (ACMA), in 2008 and 2011 during my two Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) FOI hearings, and even provided the government solicitors and ACMA with numerous documents that I collated from 1993 when the COT cases first exposed these serious problems with the Ericsson AXE exchange and the corroded CAN. These documents provide clear proof of just how bad the AXE and CAN was and how many Australian citizens were still suffering from serious problems as a result of these two faulty network pieces on telecommunications infrastructure was.

To investigate these two major network problems, download a full copy of my report, Telstra’s Falsified SVT Report, because this report explains how, during the COT cases’ arbitrations in 1994 to 1995, AUSTEL provided The Hon Michael Lee MP, then Minister for Communications, with advice regarding Telstra’s fudged testing of at least one COT case’s CAN, i.e., my business premises, even though AUSTEL knew the SVT process at my premises fudged. Remember the COT SVT was a condition AUSTEL applied to Telstra in 1993: if Telstra limited the Bell Canada International Inc testing by only testing from one exchange to another, and not testing the wiring to the COT cases’ CAN, then the SVT process had to be carried out at each of the COT cases’ business CANs, also.

Telstra had so much power over AUSTEL (the then governemnt communications regulator (now ACMA) that it forced AUSTEL to drastically reduce the numbers, as shown in the official government regulatory COT Case April 1994 Report, from some 120,000 COT-type customers who had similar CAN and Ericsson AXE problems, right around Australia (see Falsification Report File No/8) to 50-plus. Telstra was also somehow able to force AUSTEL to submit fabricated SVT reports to the minister via their third quarterly COT Cases Report of 2 February 1995.

Of course, since the arbitrator was protecting the government during our arbitrations, he found that there were no more ongoing problems affecting the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and his award of 11 May 1995 only reported on old, historic, anecdotal Telstra-related faults and ignored the still-ongoing faults that were still occurring.

Were these 120,000 COT-type customers who were having similar major problems right around Australia (see Falsification Report File No/8) also related to the Ericsson AXE telephone exchange problems that were worrying AUSTEL, as well as the CAN and Ericsson AXE problems? The information I supplied to AUSTEL between June and August 1993 (which was inadvertently left inside the allusive briefcase at my premises) showed this was possibly the case.

The following letters, dated 8 and 9 April 1994, to AUSTEL’s chair from Telstra’s group general manager, suggest AUSTEL was far from genuinely independent but instead could be manipulated to alter their official findings in their COT reports, just as Telstra requests in many of the points in this first letter. For example, Telstra writes:

“The Report, when commenting on the number of customers with COT-type problems, refers to a research study undertaken by Telecom at Austel’s request. The Report extrapolates from those results and infers that the number of customers so affected could be as high as 120 000. … (See Open Letter File No/11)

And the next day:

“In relation to point 4, you have agreed to withdraw the reference in the Report to the potential existence of 120,000 COT-type customers and replace it with a reference to the potential existence of “some hundreds” of COT-type customers” (See Open Letter File No/11)

Point 2.71 in AUSTEL’s April 1994 formal report notes:

“the number of Telecom customers experiencing COT type service difficulties and faults is substantially higher than Telecom’s original estimate of 50”.

The fact that Telstra (the defendants in the COT arbitrations) pressured the government regulator to change its original findings in the formal 13 April 1994 AUSTEL report led to the telephone problems still being experienced in 2018, twenty-two years later.

For a government regulator to reduce their findings from 120.000 COT-type complaints to read just 50 or more COT-type customer complaints is one hell of a lie told to its citizens.

Read on and learn what Telstra's highly paid lawyers achieved by lying, extorting, threatening and tampering with evidence, all with the aim of protecting an ailing government-owned Telstra Corporation.

The Briefcase Saga

It is important to return to 3 June 1993: the day two Telstra senior technical consultants inadvertently left a briefcase at my premises (see Can We Fix The Can - Copper-Wire Network).

The essential documents in that briefcase provided evidence discussing how Telstra settled with me in December 1992. Handwritten notes stating my phone problems had been continuing for months were part of this damning evidence. Most importantly, this evidence proved Telstra knew major faults still existed in its network when they commercially settled with me, telling me the problem was for sixteen days when it confirmed the faults had existed unabated for more than eighteen months. This evidence prompted AUSTEL to run a series of surveys around Australia.

Those surveys showed more than 120,000 Telstra customers were complaining of similar ongoing COT-type complaints.

The documents exposed Telstra was fully aware its inadequate service and major communication problems affected the viability of my business endeavours and other businesses throughout Telstra’s network. Official Senate estimate committee Hansard records show Senator Richard Alston, the then Shadow Minister for Communications, discussing the Problem 1 document on 25 February 1994 during a hearing.

Another previously unseen document, dated 24 July 1992 and provided to Senator Richard Alston in August 1993, includes my phone number and refers to my complaint that people ringing me get an RVA service disconnected message. A further document, dated 27 July 1992, discusses problems experienced by potential clients who tried to contact me from Station Pier in Melbourne. Some of these handwritten records go back to October 1991 and many of them were fault complaints that I did not record myself. Telstra, however, has never explained who authorised the withholding of the names of those who complained to Telstra from me. If I had known who had been unable to contact me, I could have contacted them with an alternate contact number for future reference.

And even more interesting, just like the Pulp Fiction movie: What was in the briefcase, this briefcase also had alarming documents inside that makes this COT story even more bizzar.

On 27 August 1993, Telstra’s corporate secretary wrote to me about the same ‘briefcase’ documents, noting:

“Although there is nothing in these documents to cause Telecom any concern in respect of your case, the documents remain Telecom’s property and therefore are confidential to us. …

“I would also ask that you do not make this material available to anyone else.” (See Open Letter File No/2)

Telstra’s FOI document, dated 23 August 1993, and labelled folio R09830 with the subject listed as The Briefcase, is alarming, to say the least. This document, which was copied to Telstra’s corporate secretary, notes:

“Subsequently it was realised that the other papers could be significant and these were faxed to Craig Downing but appear not to have been supplied to Austel at this point.

“The loose papers on retrofit could be sensitive and copies of all papers have been sent to Ross Marshall.” (Arbitrator File No 62)

The sensitive papers referred to above dated 23 August 1993, of which Telstra’s corporate secretary claimed, “nothing in these documents to cause Telecom any concern in respect of your case”, actually provided clear evidence that Telstra’s management concealed from me and AUSTEL (now ACMA), the actual state the network in Cape Bridgewater.

Jumping ahead (ten years)

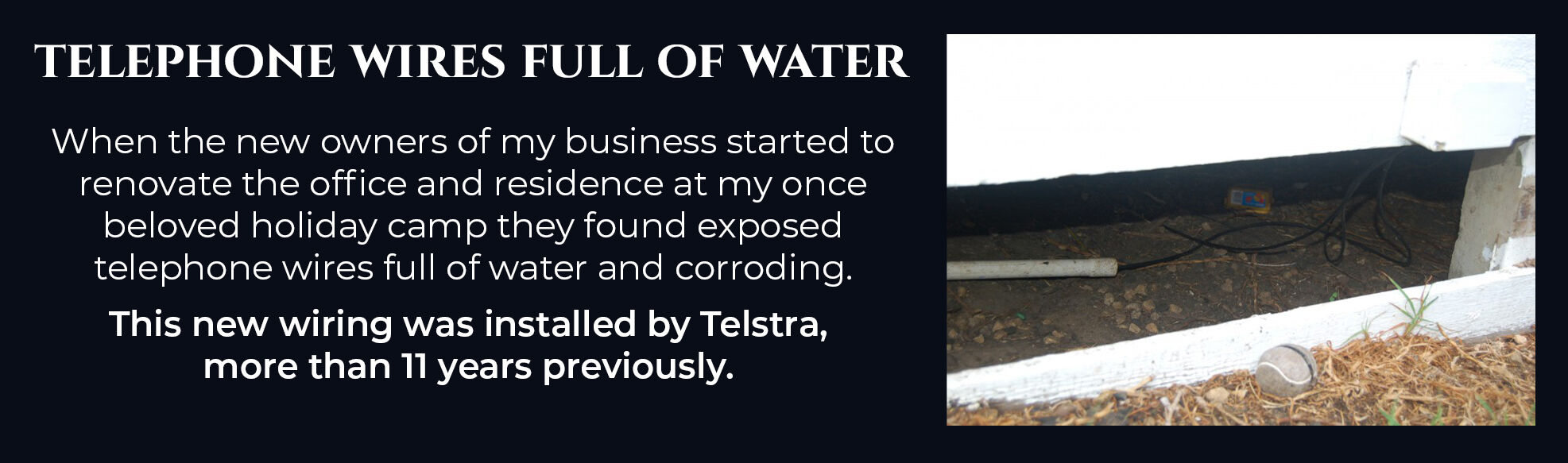

In December 2002, when the new owners of my business started to renovate the office and residence at my once beloved holiday camp, the builders assisting in this work, after pulling off the facia boards to gain access (see opposite), found exposed telephone wires full of water and corroding. This new wiring was installed by Telstra, more than 11 years previously. Page 5 of AUSTEL’s covert findings (see AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) regarding this wiring and my ongoing telephone faults confirms this when the report notes: “May 1991 (approx) New wiring installed inside and outside office and main kitchen at Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp. Rented telephone equipment replaced.” (See also the opposite photo which is part of that wiring which was still exposed all these years later. Darren Lewis, the new owner who took this photo said the dark shading underneath the wiring shown in the photo was rusty coloured that poured out of the pipe when it was disturbed.

Also in download AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings on page 10, AUSTEL bureaucrats noted:

“Whilst Network Investigation and Support advised that all faults were rectified, the above faults and record of degraded service minutes indicate a significant network problem from August 1991 to March 1993.”

Telstra not only left the wiring under the office half exposed to the elements of the Cape Bridgewater coast (the camp faces the southern ocean), but AUSTEL found Telstra “advised that all faults were rectified” while Telstra’s own records indicate there were “significant network problem from August 1991 to March 1993”.

The pressure on all four of us COT cases was immense, with television and newspaper interviews as well as our continuing canvassing of the Senate. The stress was telling by now but I continued to hammer for change in rural telephone services. The Hon David Hawker MP, my local Federal Member of Parliament corresponded with me from 26 July 1993.

“A number of people seem to be experiencing some or all of the problems which you have outlined to me. …

“I trust that your meeting tomorrow with Senators Alston and Boswell is a profitable one.” (Arbitrator File No/76)

On 18 August 1993, The Hon David Hawker MP wrote to me again, noting:

“Further to your conversations with my electorate staff last week and today I am enclosing a copy of the correspondence I have received from Mr Harvey Parker, Group Managing Director of Commercial and Consumer division of Telecom.

“I wrote to him outlining the problems of a number of Telecom customers in the Western Districts, including the extensive problems you have been experiencing.” (Arbitrator File No/77)

On 9 December 1993, the Hon David Hawker MP wrote to congratulate me for my “persistence to bring about improvements to Telecom’s country services. I regret that it was at such a high personal cost.” (See Arbitrator File No/82)

This was very affirming, as was another letter dated 9 December 1993 and copied to me from the Hon David Beddall MP, Minister for Communications, in the Labor government, who wrote:

“Let me say that the Government is most concerned at allegations that Telecom has not been maintaining telecommunications service quality at appropriate levels. I accept that in a number of cases, including Mr Smith’s there has been great personal and financial distress. This is of great concern to me and a full investigation of the facts is clearly warranted.” (Arbitrator File No/82)

AUSTEL’s formal COT cases/BCI test report was submitted to the government on 13 April 1994 (prior to the 21 April 1994 signing of the arbitration agreement and before the final COT report was provided to the communications minister). The COT case arbitration lock-up hearing, in AUSTEL’s Queen Street offices, Melbourne, in March 1994, took place seven months after Mr Davey wrote his August 1993 letter. During that hearing, Mr Davey pulled Graham Schorer, COT spokesperson, and me aside and told us Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) never investigated Telstra’s CAN in relation to the COT claims because Telstra promised AUSTEL that it would do the mandatory line testing, through the CAN, to each business in arbitration. Telstra had also promised its testing would be completed prior to arbitration.

At this meeting, AUSTEL’s chair Robin Davey also reminded Graham Schorer and me of commitments stated in a letter (dated 23 September 1992) from Telecom’s commercial and consumer managing director:

“The key problem is that discussion on possible settlement cannot proceed until the reported faults are positively identified and the performance of your members’ services is agreed to be normal. As I explained at our meeting, we cannot move to settlement discussions or arbitration while we are unable to identify faults which are affecting these services. … Until we have an understanding of these continuing and possibly unique faults, we have no basis for negotiation or settlement.” (Arbitrator File No/78, AUSTEL COT Case Report, point 5.7)

I cannot recall how many COTs attended this locked-up AUSTEL meeting, but I do remember there were at least seven of us who were quite vocal. I also recollect very clearly what I spoke about and which documents we were told we could not take out of the building. One thing was very obvious from all the security arrangements around the reading of the draft of AUSTEL’s COT Case Report: the government regulator did not want the public to know what the COT and AUSTEL investigations had uncovered in relation to the many systemic faults within Telstra’s copper wire and fibre network.

Firstly, we had the known Ericsson AXE lockup fault in the system. When the AXE phone survived locked up, this often created the terminated call to register for a further 90 seconds until after each call had ended. Just think of all the extra revenue Telstra made from its customers because of a 90-second delay in terminating each call?

Secondly, my 008/1800 service line (which was trunked through the Portland Ericsson AXE telephone exchange also had a known software lockup which kept the line open from 3 seconds, 10 seconds even up 16 seconds before terminating. Telstra was wrongly billing their customers for seconds that they did not use.

Thirdly, one problem associated with these lockup faults is that when a customer could not get through because the lines were locked up, another person ringing would receive a recorded message telling them the number they just called was not connected.

On 26 August 1993, Robin Davey wrote to the then-Minister for Communications, the Hon David Beddall MP, advising him many of the matters raised by the COT cases indicated the existence of major problems in Telstra’s network. Eventually, I received a copy of this letter under FOI and found that, on page 4, under the heading “Cape Bridgewater,” AUSTEL notes, “Telecom has admitted existences of unidentified faults to AUSTEL.”

It was the unidentified fault information that I discussed with Robin Davey had to be held in the government offices and should have been made availabe to me during the AUSTEL investigations by either Senator Bob Collins or David Bedall MP.

Next Page ⟶