Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers—government Corruption. Read about the corruption within the government bureaucracy that plagued the COT arbitrations.

By hovering your mouse or cursor over the following images, you can learn more about the truth surrounding our casualties of Telstra story.

📘 Call for Justice

My name is Alan Smith. This is the story of my battle with a telecommunications giant and the Australian Government—a battle that has twisted and turned since 1992, winding through elected governments, government departments, regulatory bodies, the judiciary, and the Australian telecommunications giant, Telstra, or Telecom, as it was known when this story began. The quest for justice continues to this day.

My story began in 1987, when I decided that my life at sea—where I had spent the previous 28 years—was over. I needed a new land-based occupation to see me through to retirement and beyond.

Hospitality was my calling, and I had always dreamed of running a school holiday camp. Imagine my delight when I saw the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre advertised for sale in The Age. It was nestled in rural Victoria, near the maritime port of Portland. Everything seemed perfect. I performed my due diligence to ensure the business was sound—or at least, all the due diligence I was aware of. Who would have guessed I needed to check whether the phones worked?

Within a week of taking over the business, I knew I had a problem. Customers and suppliers alike were telling me they couldn’t get through. Yes, that’s right—I had a business to run and a phone service that was, at best, unreliable, and at worst, not there. Of course, we lost business as a result.

And so, my saga begins. It has been a quest to get a working phone at the property. Along the way, I received some compensation for business losses and many promises that the problem was resolved. It never was. I sold the business in 2002, and subsequent owners have suffered the same fate.

Other independent businesspeople similarly affected by poor telecommunications joined me on this journey. We became known as the Casualties of Telecom—or the COT cases. All we ever wanted was for Telecom/Telstra to acknowledge our problems, rectify them, and compensate us for our losses. A working phone—is that too much to ask?

We initially called for a full Senate investigation into Telecom and these issues. Instead, we were offered an arbitration process. It seemed like a fair way to resolve the problem, so we accepted. At that early stage, we genuinely believed the technical faults would be addressed.

No such luck. Suspicions that something was deeply wrong with the arbitration process surfaced almost immediately. We had been promised access to the Telecom documents needed to make our case. Despite that promise, those documents were never provided. We still don’t have them.

Then came the discovery that our fax lines were being illegally tapped during arbitration. With the weight of the government against us, we lost.

Worse still, we were tricked into signing confidentiality clauses that have hampered our efforts ever since. I may be breaching those clauses by making this public—but what choice do I have?

We turned to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to obtain the documents we were promised. We know the evidence exists—proof that our lines were faulty and improperly tested. But without access, justice remains out of reach.

So I ask you: Are we imagining this? Or has there truly been massive corruption and collusion among public servants, politicians, regulatory bodies, and Telstra itself—protecting Telstra at the expense of rural Australian businesses?

📘 Whistleblowers: The Last Line of Defence Against Institutional Betrayal

The twelve chapters featured at the bottom of the Absent Justice homepage—ranging from Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page to The Promised Documents Never Arrived—remain in draft form, pending final editing. Each chapter is supported by a series of exhibits, many of which were obtained through the Australian Freedom of Information Act (FOI Act) after years of effort. Together, they underpin the mini-stories on absentjustice.com, weaving a vivid tapestry of deception, injustice, and bureaucratic decay. While these chapters may eventually be archived, their purpose is enduring: to expose the systemic failures that corrupted the Casualties of Telstra (COT) arbitrations and to honour those who had the courage to speak out.

In their place, we shine a light on whistleblowers—those extraordinary individuals who risk everything to reveal truths buried beneath layers of institutional deceit. These are not mere informants; they are moral sentinels. Their courage is not born of ambition, but of conscience. They refuse to be complicit, choosing instead to confront injustice head-on.

Governments worldwide must recognise that democracy cannot survive without whistleblowers. History is unequivocal: from Watergate to WikiLeaks, from the COT Cases to the British Post Office scandal, it is whistleblowers who have pierced the veil of corruption and forced accountability.

📘 Was Julian Assange among them?

In 1994, three teenage hackers contacted Graham Schorer, COT spokesperson, warning that Telstra was acting illegally. Was Julian Assange among them? Their offer of critical arbitration files was declined—out of fear, mistrust, and bitter experience. The documents never came. The deception endured. Senate Hansard later confirmed Telstra’s misconduct. But the damage was done.

These hackers, like so many whistleblowers, were driven by a moral imperative. They saw injustice and chose action. Their motives transcended the breach of infrastructure—they sought to protect citizens from a rigged system. Their warnings, documented in statutory declarations and investigative reports, were tragically ignored.

Whistleblowers often face persecution, gaslighting, and retaliation. When I reported Telstra’s misconduct to the Australian Federal Police, I was penalised. Telstra carried out its threats. This is the cost of truth-telling in a system designed to protect the powerful.

The COT saga echoes the UK’s Post Office scandal, where sub-postmasters were misled, jailed, and driven to despair by a government-owned entity. Like Telstra, the Post Office promised transparency and delivered betrayal. Thirty years later, the COTs still await the documents that were meant to substantiate their claims.

Whistleblowers are our last line of defence. They illuminate transgressions that might otherwise go unnoticed. Their stories are not just warnings—they are blueprints for reform. We must protect them, amplify their voices, and learn from their sacrifices.

Let us stand together to honour whistleblowers—not as rebels, but as guardians of truth.

Would you like this formatted for your homepage, paired with audio narration, or broken into sections for a visual timeline? I can also help you build a companion piece comparing the COT revelations to other global whistleblower cases.

📘 The Infrastructure of Concealment

Until the late 1990s, I uncovered and exposed a disturbing nexus of corruption involving senior bureaucrats within the Australian government and the then-state-owned Telstra Telecommunications Carrier. This corruption extended into the ownership and operation of essential services, where public trust was routinely betrayed for private gain.

My efforts to bring this misconduct to light culminated in two Administrative Appeals Tribunal hearings—V2008/1836 and 2010/4634—where I presented evidence detailing how this entrenched corruption had sabotaged my 1994/1995 arbitration and the government-endorsed 2006 arbitration review process. These hearings were not just legal proceedings; they were platforms where I laid bare the systemic rot that had infected key institutions.

Ethical questions

🔥 Ericsson’s Global Bribery Scandal: The Corruption That Crushed the COT Cases

Ericsson, the company at the heart of my Portland exchange complaints, has admitted to a years-long campaign of corruption across five countries. The U.S. Department of Justice revealed that Ericsson used slush funds, bribes, and falsified records to secure telecom contracts—including in Australia, where they partnered with Telstra after Huawei was banned.

This wasn’t just corporate misconduct. It was a global operation of deceit, with Australia caught in its web.

🧠 The Breach Went Deeper: Lane, Ericsson, and the Data That Disappeared

My assertion that Lane Telecommunications was unfit to evaluate my arbitration claims—due to prior ties with Telstra—is echoed in broader concerns about conflict of interest. Lane was allowed to retain my Ericsson-related fault data even after Ericsson acquired them. This occurred despite my claims against Telstra for deploying known defective Ericsson AXE exchange equipment, which other nations were actively removing from their networks.

Telstra’s decision to rely on this equipment—while ignoring its global rejection—shows a blatant disregard for the integrity of our claims. These deficiencies were not minor. They were the very reason the COT Cases entered arbitration: to salvage businesses crippled by faulty infrastructure.

This disregard for our right to a functioning telephone service undermined the entire arbitration process. It wasn’t just flawed—it was corrupted.

🕳️ A Treacherous Web: Ericsson, Telstra, and the Theatre of Betrayal

The most sinister chapter of this saga lies buried in Australia—within the government-sanctioned arbitration proceedings that were supposed to deliver justice to the COT Cases.

Instead, those proceedings became a theatre of betrayal.

Ericsson, operating with impunity, acquired Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd, the very firm appointed as the arbitration’s technical consultant. This covert acquisition—executed while Lane was actively evaluating Telstra’s use of Ericsson’s compromised AXE exchange equipment—was not just unethical. It was a deliberate infiltration of the justice process, a move so brazen it defies belief.

The AXE system was already discredited globally. Nations were ripping it from their exchanges. Yet Telstra and Ericsson clung to it, knowingly deploying defective infrastructure that crippled businesses like mine.

And while we fought for survival, Ericsson bought the witness—silencing scrutiny with a corporate handshake.

Despite Telstra’s arbitration unit swearing under oath in nine separate witness statements that they had no knowledge of faults in the AXE exchange that could impact my holiday camp business, the truth lies in two internal Telstra file notes. These documents reveal that Telstra was fully aware of the escalating severity of AXE faults, which worsened as more customers were connected to the Portland exchange.

⚠️ The Call for Reckoning

This manipulation of justice reveals a shocking disregard for transparency and accountability, leaving victims trapped in a labyrinth of institutional betrayal while the true architects of corruption remain shielded from scrutiny.

I call on the Australian government to expose the dark machinations that enabled Ericsson to infiltrate the arbitration process. The evidence is clear. The conflict is documented. The betrayal is undeniable.

“Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnected.

“They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE.” (See False Witness Statement File No 3-A)

To further support my claims that Telstra already knew how severe my Ericsson Portland AXE telephone faults were, can best be viewed by reading Folios C04006, C04007 and C04008, headed TELECOM SECRET (see Front Page Part Two 2-B), which states:

“Legal position – Mr Smith’s service problems were network related and spanned a period of 3-4 years. Hence Telecom’s position of legal liability was covered by a number of different acts and regulations. … In my opinion Alan Smith’s case was not a good one to test Section 8 for any previous immunities – given his evidence and claims. I do not believe it would be in Telecom’s interest to have this case go to court.

“Overall, Mr Smith’s telephone service had suffered from a poor grade of network performance over a period of several years; with some difficulty to detect exchange problems in the last 8 months.”

Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd, appointed as the technical consultant for the arbitration process, played a significant role in the case involving Ericsson, particularly given Ericsson's acquisition of the company during the COT arbitration proceedings. During this process, Lane Telecommunications reportedly communicated to the arbitrator that the AXE voice message had only been active for a mere fourteen days on my account. This claim, which significantly downplayed the actual duration of the service, served as the basis for the arbitrator's ruling, which awarded compensation solely for the limited fourteen days.

However, government records clearly indicate that the service in question lasted for several years, contradicting the assertion made by Lane Telecommunications. The misinformation presented not only reflects poorly on the credibility of the arbitration process but also highlights the severe repercussions faced by the COT Cases. The deliberate manipulation of facts and the alleged purchase of a witness by Ericsson from Australia have undermined the integrity of these proceedings and resulted in substantial financial losses for the COT Cases.

What’s more disturbing is the Australian government’s conspicuous silence. No inquiry. No accountability. Just a void where justice should have stood. The arbitrator and their advisors didn’t just fail us—they constructed a treacherous framework of deception, one that ensured our claims would be buried beneath layers of scandal and lawlessness.

This was not incompetence. It was a calculated betrayal of public trust.

Victims were left wandering a labyrinth of institutional betrayal, while the true architects of corruption remained shielded—protected by the very system that promised resolution. The evidence, including Google-linked documentation and Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden, makes it glaringly apparent:

I call on the Australian government to tear down the veil. To expose the dark machinations that allowed Ericsson to infiltrate a legal process meant to protect its citizens. This is not just a demand for answers; it is a call for action. It is a demand for reckoning.

Read about the dealings with Ericsson on 19 December 2019, as reported in the Australian media, because it is firmly intertwined in the corrupt practices of both Telstra and Ericsson, and those who administered the COT arbitrations between 1994 and 1998. This media release states:

"One of Telstra's key partners in the building out of their 5G network in Australia is set to fork out over $1.4 billion after the US Department of Justice accused them of bribery and corruption on a massive scale and over a long period of time.

Sweden's telecoms giant Ericsson has agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion following an extensive investigation which saw the Telstra-linked Company 'admitting to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business." https://www.channelnews.com.au/key-telstra-5g-partner-admits-to-bribery-corruption/

The Path to Betrayal: A Call for Accountability

The U.S. Department of Justice has unearthed a chilling truth about Ericsson’s global telecommunications operations and their disturbing ties to international corruption and terrorism. The revelations surrounding the Casualties of Telstra (COT) Cases expose a deeply entrenched web of deceit, raising urgent questions about how Ericsson was allowed to operate with impunity, even acquiring the key technical witness during government-sanctioned arbitration proceedings that scrutinised their compromised telephone equipment.

It is both baffling and deeply troubling that the Australian government has remained conspicuously silent in the face of such egregious misconduct. Ericsson’s covert acquisition of Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd—while Lane was engaged as the arbitration’s technical consultant—suggests a deliberate manipulation of the process. This manoeuvre occurred amid serious allegations that Telstra and Ericsson knowingly relied on discredited Ericsson AXE exchange equipment, a flawed system that many nations have since abandoned due to its critical deficiencies (see File 10-B ).

Australia's Bureaucrats closed their eyes to this conflict of interest

To underscore the scale of what I am exposing, the Herald Sun reported on 22 December 2008 under the heading "Bad Bureaucrats" that over a thousand bureaucrats had been implicated in corrupt practices between 2007 and 2008 alone, and I quote from that article:

“Hundreds of federal public servants were sacked, demoted or fined in the past year for serious misconduct. Investigations into more than 1000 bureaucrats uncovered bad behaviour such as theft, identity fraud, prying into file, leaking secrets. About 50 were found to have made improper use of inside information or their power and authority for the benefit of themselves, family and friends“

This wasn’t a coincidence—it was confirmation. My testimony, which is also attached here as Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2, aligns with a broader reckoning, revealing that what I had endured was part of a much larger pattern of institutional betrayal.

During the COT arbitrations, I became a target of this corrupt system. The treachery I encountered was not a mere anomaly; it was deeply embedded within the very fabric of the bureaucracy. This realisation propelled me to create absentjustice.com, a platform dedicated to unveiling the deceit and betrayal that defined those proceedings. I meticulously chronicled every deceitful manoeuvre, every backstab, and every act of betrayal as this corruption entered another horrific phase, known as the Robodebt affair.

A Precursor to Robodebt

This dark chapter in Telstra’s history foreshadowed the Robodebt scandal of 2023, where automated debt recovery systems—based on flawed algorithms and government indifference—led to widespread suffering. Just as Telstra’s victims were coerced into paying for faults they didn’t cause, Robodebt victims were pursued for debts they didn’t owe.

The consequences were devastating. Heart attacks. Mental breakdowns. Suicides. Families are shattered under the weight of government-sanctioned abuse. The parallels are chilling: both schemes relied on corrupted data, bureaucratic complicity, and a ruthless disregard for human life.

This serves as further proof that the issue lies not with the actual politicians—who are, for the most part, upstanding citizens genuinely trying to make a difference in the world, regardless of differing political views—but instead with the government lobbyists and bureaucrats mentioned in the Herald Sun newspaper article dated December 22, 2008, under the heading: "Bad Bureaucrats".

On 23 May 2021, Peta Credlin, a high-profile Australian media guru and TV host, wrote a fascinating article, also in the Herald Sun newspaper, under the heading:

"Beware The Pen Pusher Power - Bureaucrats need to take orders and not take charge”, which noted:

“Now that the Prime Minister is considering a wider public service reshuffle in the wake of the foreign affairs department's head, Finances Adamson, becoming the next governor of South Australia, it's time to scrutinise the faceless bureaucrats who are often more powerful in practice than the elected politicians.

Outside of the Canberra bubble, almost no one knows their names. But take it from me, these people matter.

When ministers turn over with bewildering rapidity, or are not ‘take charge’ types, department secretaries, and the deputy secretaries below them, can easily become the de facto government of our country.

Since the start of the 2013, across Labor and now Liberal governments, we’ve had five prime ministers, five treasurers, five attorneys-general, seven defence ministers, six education ministers, four health ministers and six trade Ministers.”

🧨 The Arbitration That Shielded Parasites

Leading up to and during my 1994 government-endorsed arbitration, it became painfully clear that no authority—not even the Australian Federal Police—had the power or will to act. My evidence, alongside that of other COT Cases, showed our businesses were deliberately targeted. The four principal COT Cases weren’t just collateral damage—we were hunted.

Telstra’s legal arm, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne), operated like a rogue unit. Denise McBurnie, the architect of the notorious COT Strategy, drafted it with surgical malice → Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C. Wayne Maurice Gondon signed arbitration witness statements falsely attesting they had been signed by Telstra witnesses—when they hadn’t. These weren’t clerical errors. They were calculated acts of deception.

⚖️ The Arbitration Agreement That Should Never Have Been Used

As shown in government records, seven months before our arbitrations began, the four COT Cases—including mine—were assured by the government (see Point 40, Prologue Evidence File No/2) that the law firm Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne) would have no further involvement in our matters. Their conduct had been deemed unethical in their dealings with us.

But behind closed doors, Freehill Hollingdale & Page drafted our arbitration agreement—the very document that would define the terms of our pursuit of justice. We were never told. And worse, the arbitrator himself, Dr Gordon Hughes, later declared that same agreement not credible for use in my arbitration. Yet he used it anyway, as the following letter from Dr Hughes to Warwick Smith shows:

“the time frames set in the original Arbitration Agreement were, with the benefit of hindsight, optimistic;

“in particular; we did not allow sufficient time in the Arbitration Agreement for inevitable delays associated with the production of documents, obtaining further particulars and the preparation of technical reports; …

“In summary, it is my view that if the process is to remain credible, it is necessary to contemplate a time frame for completion which is longer than presently contained in the Arbitration Agreement.” (Open Letter File No 55-A)

We were given an ultimatum: sign the agreement or the arbitrator and administrator, Warwick Smith, would walk away. There was no negotiation. No transparency. Just the one threat, sign it or take Telstra to court.

🏕️ Retreat into Shadows: The COT Cases and the Death of Hope

I used my holiday camp for a two-night self-help retreat, hoping to find some bearings—some clarity on where to go from here. But what unfolded during those two days was far more chilling than I had anticipated. This was in 1993.

As I sat with the other COT Cases, I began to see it—really see it. Some of them believed they were already dead.

Each story felt like a descent into a haunted abyss. Their narratives weren’t just about struggle—they were soaked in despair, wrapped in a sinister shroud that clung to every detail. As I sifted through their accounts, a creeping dread settled in my bones. It became shockingly clear: some of these individuals had resigned themselves to a fate worse than death—existence without hope.

Their expressions were haunting. Faces etched with pain and hopelessness. Eyes that once gleamed with life now reflected a profound void, drained of warmth, drained of fight. In our discussions, I felt an eerie tension—like walking a tightrope over an abyss. They had stepped back from the edge of existence, accepting a fate that left them wandering in a liminal space between life and death.

This revelation wasn’t just unsettling—it was terrifying. These fragile souls had declared themselves lost, retreating into a darkness from which they could no longer see a path back. I felt as though I was peering into the shadows of their minds, witnessing the treachery of despair that had ensnared them.

In July 2005, Senator Barnaby Joyce held a meeting at the Brisbane Polo Club, attended by fourteen individuals who had been affected by Telstra's controversial and disrupted arbitration and mediation process. During the meeting, these individuals shared their similar experiences, and Senator Joyce displayed a profound emotional response as he recognised how detrimental government bureaucracy can be, leading to a significant decline.

The government agreed to resolve the fourteen unresolved arbitration issues concerning COT (Customers of Telstra) if Senator Joyce would cast his crucial vote in the Senate to pass the Telstra privatisation legislation. He willingly agreed to cast his vote, a decision clearly depicted in the accompanying image. Additionally, a letter he sent me on September 15, 2005, further illustrates his commitment to resolving our COT issues.

15 September 2005, Senator Barnaby Joyce writes to me:-

“As a result of my thorough review of the relevant Telstra sale legislation, I proposed a number of amendments which were delivered to Minister Coonan. In addition to my requests, I sought from the Minister closure of any compensatory commitments given by the Minister or Telstra and outstanding legal issues. …”

“I am pleased to inform you that the Minister has agreed there needs to be finality of outstanding COT cases and related disputes. The Minister has advised she will appoint an independent assessor to review the status of outstanding claims and provided a basis for these to be resolved.”

“I would like you to understand that I could only have achieved this positive outcome on your behalf if I voted for the Telstra privatisation legislation.” (Senate Evidence File No 20)

Once Senator Joyce cast the pivotal vote—one that was teetering precariously in the balance—he etched his name into the annals of history for both the Telstra Corporation and the Liberal-National Coalition Government. However, in a surprising turn, Senator Coonan quickly reneged on her prior commitment, executing a decisive back-flip that many of the letters collected on this website starkly illustrate.

However, what followed was anything but just, as demonstrated by the outcomes associated with 'The eighth remedy pursued.'

The actions taken by Telstra’s executives and government bureaucrats during this process—initiated by Joyce’s good faith—were criminal, undemocratic, and ruthless. They didn’t just abandon the agreement. They weaponised it. They used the momentum of privatisation to bury our cases deeper, shielding misconduct behind corporate walls.

This episode stands as a testament to the state of disarray the government was already in—and the even more profound crisis it has since become. The abandonment of the COT Cases wasn’t just a policy failure. It was a betrayal of democratic trust, a silencing of truth, and a warning to every citizen who dares to believe in accountability.

These were the same executives who masterfully orchestrated a staggering $400 million deal with Rupert Murdoch and Fox, all for the ambitious rollout of Telstra's fibre cable infrastructure. They did this while feigning a commitment to an unrealistic deadline, despite Senate Hansard exposing the fact that the Telstra board was already aware that the project’s timeline was nothing more than a fabricated illusion. This was not merely a case of poor management; it was a calculated scheme of deception, disguised as progress and innovation.

The warning signs were glaringly apparent at every turn. As the involvement of Rupert Murdoch illustrates, the deception ran deep, casting a long shadow over the entire operation and tainting the integrity of the government bureaucracies.

A few months after that meeting, Telstra’s government lobbyist Paul Rumble emerged from the shadows. His threats nearly broke me. I went down on my knees. The referee counted eight. But I got up. I hit the deck running and took the punches one after another.

Paul Rumble and his ilk weren’t just thugs. They were parasites—protected, emboldened, and insulated by the very arbitration process that was supposed to deliver justice.

🧑⚖️ The Architects of Silence: Hughes, Pinnock, and Rundell

As of 2025, Dr Gordon Hughes serves as Principal Lawyer at Davies Collison Cave Lawyers in Melbourne (https://shorturl.at/L4tbp). But long before that title, he played a central role in a deeply compromised arbitration process—one that derailed my pursuit of justice.

Despite clear evidence showing that Dr Hughes, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to the COT arbitrations), and John Rundell (Project Manager to the arbitrations) were involved in a joint conspiracy to mislead and deceive the President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, Laure James, none of them has come forward to explain their actions.

My claims were valid. The arbitration process was conducted outside the agreed-upon ambit of procedures. This wasn’t a technical error—it was a deliberate manoeuvre to destroy my appeal process and silence my evidence.

To this day, not one of them has explained. Not one has acknowledged the damage done. Their silence is not just professional—it’s personal. It’s a refusal to face the truth they helped bury.

Threats made and carried out during my arbitration

On July 4, 1994, amidst the complexities of my arbitration proceedings, I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra representative on the arbitration defence team. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred an entire month before the arbitrator was legally obligated to share such information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. I invested considerable effort in crafting this detailed letter, carefully selecting every word. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no intention of submitting any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardise my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could impact the arbitrator's decisions regarding my case.

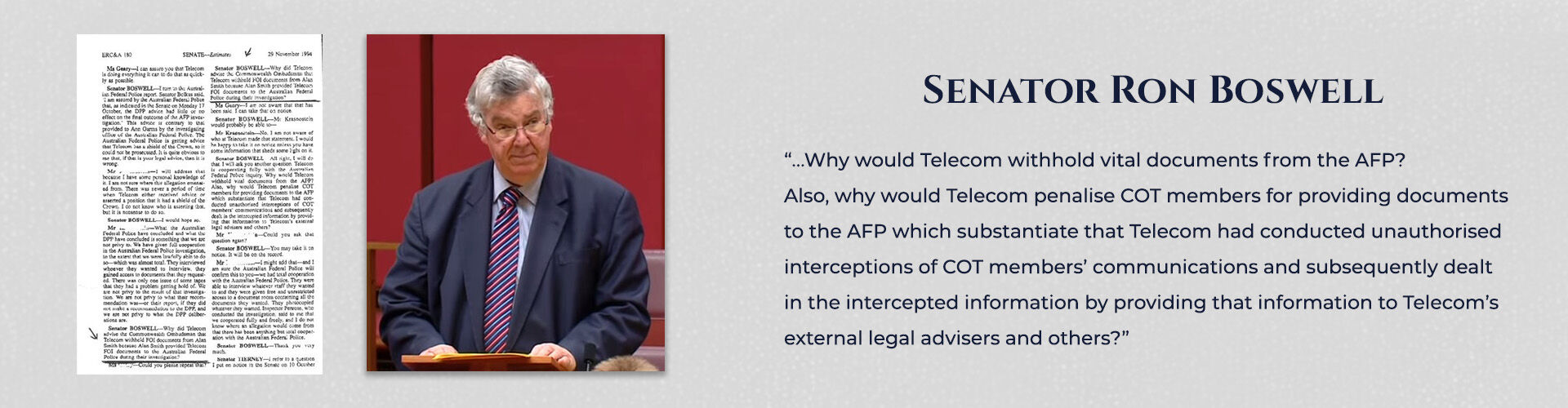

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on 26 September 1994. During this visit, they began to pose probing questions regarding my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result of this situation, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the attention of the Senate. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this: no one in the TIO office or government has ever investigated the disastrous impact the withholding of documents had on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen, who had assisted the AFP in their investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations, was so severely disadvantaged during a civil arbitration.

Additionally, in the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 I provide a comprehensive account establishing Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

• The arbitration process was compromised by covert monitoring.• Telstra insiders shared private data with intermediaries.• Government agencies failed to act on credible threats and evidence.• The arbitrator ignored critical breaches of privacy and due process.

Exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) clearly show that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

This particular individual is the former Telstra Portland technician who supplied this unknown person named 'Micky' with the phone and fax numbers that I used to contact them via my telephone service lines (Refer to Exhibit 518 FOI folio document K03273 -AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541).

At the time, my body was reeling from the lower gut punches. Two Australian senators on 24 June 1997, asked several questions of Telstra (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia Senator Kim Carr states to Telstra’s primary arbitration defence Counsel (Re: Alan Smith:

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

What alarms me most about Telstra’s intelligence operations in Australia is this: who inside Telstra had the government clearance and expertise to filter the raw information they were collecting before it was catalogued for future use? Who was vetting this data? Who was protecting it? And more importantly, who was protecting us?

I have serious concerns about the confidential information Telstra gathered during my phone conversations with former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser in April 1993 and again in April 1994. We discussed Telstra officials and my “Red Communist China” episode. That information was sensitive, personal, and politically charged. And yet, it was intercepted, stored, and our conversations redacted.

When Telstra was fully privatised in 2005, who in Australia was given the charter to archive this material? Decades of surveillance, customer data, and intelligence—where did it go? Who holds it now? There’s no transparency. No accountability. Just silence.

🥊 Setting the Record Straight: The Sheriff Incident

The version of events reported in Senator Hansard only tells part of the story. What it omits is the desperation and injustice I faced that day.

The Sheriff and his two henchmen arrived with orders to strip my business of essential catering equipment—tools I needed to keep trading. My bankers had lost patience and sent them to ensure I stayed on my knees. This wasn’t enforcement. It was punishment.

Let me be clear: I threw no punches. But when the Sheriff moved to seize my equipment, I placed him in a wrestling hold—a ‘Full Nelson’—and walked him out of my office. It was a moment of defiance, not violence. I was protecting my livelihood, not attacking anyone.

The Magistrates' Court later dropped all charges on appeal. The court recognised his story had two sides, and mine was rooted in survival.

Strategies for Survival

So how does one tell a story like this without falling prey to legal retaliation?

• I document everything. Time stamps. Statutory declarations. Senate records. I build a fortress of facts.

• I anonymise where necessary. I use composite characters and layered narrative to protect identities while preserving truth.

• I publish through platforms that honor whistleblowers. I consult legal experts. I embed my evidence in memoir, in culinary disaster, in the rhythm of shipboard life.

• I let the reader feel the dread. The silence. The betrayal.

The Unanswered Questions

How many other arbitrations were compromised by this insidious surveillance? Is this form of electronic eavesdropping still a problem in legitimate processes today? How many lives were ruined while the government compensated the powerful and ignored the pleas of its own citizens? And what does it say about a nation when one of its richest sons sacrifices his citizenship to become American, while the rest of us are left to fight for justice in the land we call home?

This chapter is not the end. It is a beginning. A signal flare in the fog. A call to those who still believe in truth, in accountability, and in the power of one voice to pierce the silence

Unmasking the Machinery of Betrayal

How does one begin to tell a story so steeped in treachery, so riddled with deceit, that it threatens to shake the very foundations of trust in our institutions? How does one, armed only with truth and a battered fax machine, stand against a government-endorsed process that masqueraded as justice while quietly feeding privileged information to the defendants—Telstra, then a government-owned telecommunications giant?

This is not a tale of paranoia. It is a chronicle of documented sabotage. It is the story of how I, and others like me, were systematically undermined during arbitration processes that were supposed to deliver fairness. Instead, they delivered silence, obstruction, and a chilling form of surveillance that still haunts me.

The Vanishing Faxes

In January 1999, a group of arbitration claimants submitted a damning report to the Australian Government. It revealed that confidential documents—faxed in good faith—were being intercepted, screened, and manipulated before reaching their intended recipients. In my case, six critical claim documents vanished. The arbitrator’s secretary admitted they were never received. Yet I was denied the right to resubmit them.

My fax account tells a different story. It shows I dialled the correct number every time. And years later, one of the technical consultants who reviewed those transmissions stood by his statutory declaration: the faxes had passed through a secondary machine before being retransmitted. Dual time stamps told the tale. The evidence was irrefutable.

During the investigation by the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group into the alleged fraudulent conduct by Telstra during and after the COT arbitrations, the Scandrett & Associates report was delivered to Senator Ron Boswell on 7 January 1999. This report confirmed that faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations (refer to Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13). Furthermore, one of the two technical consultants who verified the validity of this fax interception report contacted me via email on 17 December 2014, emphasising the importance of these findings.

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

The evidence within this report Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) also indicated that one of my faxes sent to Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was similarly intercepted, i.e.,

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

A Chilling Revelation

While working on my manuscript, "R'ng for Justice," I shared an early draft with Helen Handbury, Rupert Murdoch's sister, and Senator Kim Carr. On January 27, 1999, Senator Kim Carr provided his feedback on this draft:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

Helen Handbury had visited my holiday camp twice and witnessed firsthand the torment I endured. Upon reading Senator Kim Cary Carr's response story, she was visibly shaken. “I will get Rupert to have it published,” she said. “He will be shocked.”

What horrified Helen wasn’t just the illegal fax hacking—it was the scale of it. The fact that it continued even during her second visit. The fact that I had provided evidence to the Australian Federal Police, showing that this surveillance dated back to at least September 1992, is referred to in the AFP transcript → Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1, which discusses this evidence.

Despite this, the arbitrator refused to allow me to resubmit the missing documents.

At the time, the News of the World hacking scandal hadn’t yet erupted. But Helen saw the parallels. She saw the rot.

The $400 Million Question: Blood Money in the Boardroom

Helen Handbury wasn’t just shaken—she was horrified. What I laid before her wasn’t a mere tale of bureaucratic failure. It was a blueprint of institutional rot. A system so corrupted, so brazen in its contempt for ordinary Australians, that it rewarded the powerful while grinding the rest of us into dust.

The illegal fax interceptions. The denial of natural justice. The surveillance. The obstruction. All of it was bad enough. But then came the revelation that turned Helen pale: Rupert Murdoch—her own brother—had quietly received $400 million in compensation from Telstra. A payout cloaked in silence, sanctioned by a government-owned corporation that was simultaneously dragging everyday citizens through the mud of arbitration and mediation.

I showed Helen the Senate Hansard records. They weren’t vague. They weren’t speculative. They were damning. Members of Parliament were deeply alarmed. The entire Telstra board knew—knew—that Telstra could not meet the licensing obligations tied to that $400 million deal. And yet, they signed it anyway. They pushed it through. They handed over the money.

Who approved this grotesque transaction? Who, in the shadows of the boardroom, decided that the Australian public—who owned Telstra—should foot the bill for Murdoch’s empire while the rest of us were denied justice? This wasn’t incompetence. It was collusion. It was calculated. It was criminal.

Helen struggled to process it. She had seen the toll these arbitrations took on people like me. She had walked through my camp, listened to my story, and seen the evidence with her own eyes. And now, faced with the knowledge that her brother had been compensated while others were crushed under the weight of legal costs, she was deeply disturbed.

This wasn’t just about money. It was about betrayal. About a government and a corporation that conspired to silence dissent, conceal misconduct, and reward the elite. It was about a boardroom decision that reeked of underhanded skullduggery—one Helen could not reconcile.

She wanted Rupert to see my story. Whether she ever shared it, I’ll never know. She passed away before I could deliver the second draft. Her husband, Geoffrey Handbury, wrote me a kind letter, saying he was too old to pursue it. But the truth had already begun to surface. Senate records later confirmed it: Telstra’s board knew it couldn’t meet its agreement with Fox—and proceeded anyway.

They did it with full knowledge. They did it with impunity. And they did it while the rest of us were left to rot.

The Machinery of Collusion

The deeper I dug, the more grotesque the architecture of corruption revealed itself. This wasn’t a one-off payout. It was a symptom of something far more insidious—a machinery of collusion operating behind closed doors, where truth was suffocated and justice was bartered away.

The Senate Hansard records were not just concerned—they were alarmed. They documented a government-owned corporation knowingly entering into a contract it could not fulfil. Telstra’s board was fully aware that it would fail to meet the licensing obligations tied to the $400 million compensation deal with Rupert Murdoch’s Fox empire. And yet, they proceeded. No hesitation. No accountability. Just a rubber stamp and a transfer of wealth.

This wasn’t corporate negligence. It was state-sanctioned betrayal.

The implications were staggering. Telstra, still owned by the Australian public at the time, had effectively siphoned taxpayer money into the hands of one of the world’s wealthiest media moguls. Meanwhile, ordinary Australians—claimants like me—were being surveilled, sabotaged, and silenced in arbitration processes that were supposed to protect us.

The same Telstra that intercepted my faxes. The same Telstra that denied me the right to resubmit missing documents. The same Telstra that built its defence on stolen information. That Telstra was simultaneously cutting secret deals with Murdoch while trampling over its own citizens.

And the government? It watched. It knew. It did nothing.

Please note that I have deliberately selected the segment about Rupert Murdoch on the home page due to his controversial reputation. This example vividly illustrates how the government in Australia often extends privileges and support to large corporations, while individuals like myself, who dare to challenge the systemic issues that foster discrimination, receive little to no assistance.

Immediately following the accounts of Rupert Murdoch and Helen Handbury, readers will find the intricate saga involving Dr Gordon Hughes, John Pinnock, and John Rundell: "The Open Letter" dated 25/09/2025, which is part of the unfinished Chapter Five. This narrative sheds light on the uncomfortable truth: the same government that turned a blind eye to the Murdoch situation in the mid-1990s also permitted these three arbitration administrators to fabricate false statements and tarnish my reputation. Their actions were clearly intended to derail the investigation led by Laure James, the then-President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, into my serious allegations regarding the improper conduct of my arbitration process.

10. Telstra's CEO and Board have known about this scam since 1992. They have had the time and the opportunity to change the policy and reduce the cost of labour so that cable roll-out commitments could be met and Telstra would be in good shape for the imminent share issue. Instead, they have done nothing but deceive their Minister, their appointed auditors and the owners of their stockÐ the Australian taxpayers. The result of their refusal to address the TA issue is that high labour costs were maintained and Telstra failed to meet its cable roll-out commitment to Foxtel. This will cost Telstra directly at least $400 million in compensation to News Corp and/or Foxtel and further major losses will be incurred when Telstra's stock is issued at a significantly lower price than would have been the case if Telstra had acted responsibly.

11. Telstra not only failed to act responsibly, it failed in its duty of care to its shareholders. So the real losers are the taxpayers and to an extent, the thousands of employees who will be sacked when Telstra reaches its roll-out targetÐcable past 4 million households, or 2.5 million households if it is assumed that Telstra's CEO accepts directives from the

“Mr Smith still believes that there are many unanswered questions by the regulatory authorities or by Telstra that he wishes to pursue and he believes these documents will show that his unhappiness with the way he has been treated personally also will flow to other areas such as it will expose the practices by Telstra and regulatory bodies which affects not only him but other people throughout Australia.

“Mr Smith said today that he had concerns about the equipment used in cabling done at Cape Bridgewater back in the 1990s. He said that it should – the equipment or some of the equipment should have a life of up to 40 years but, in fact, because of the terrain and the wet surfaces and other things down there the wrong equipment was used.”

Another document I provided to the arbitrator in 1994 and the AAT in 2008, and again in 2011, is a Telstra FOI (folio A00253) dated 16 September 1993, titled Fibre Degradation. It states:

“Problems were experienced in the Mackay to Rockhampton leg of the optical fibre network in December ’93. Similar problems were found in the Katherine to Tenant Creek part of the network in April this year. The probable cause of the problem was only identified in late July, early August. In Telecom’s opinion the problem is due to an aculeate coating (CPC3) used on optical fibre supplied by Corning Inc (US). Optical fibre cable is supposed to have a 40 year workable life. If the MacKay & Katherine experience are repeated elsewhere in the network, in the northern part of Australia, the network is likely to develop attenuation problems within 2 or 3 years of installation. The network will have major QOS problems whilst the CPC3 delaminates from the optical fibre. There are no firm estimates on how long this may take. …

“Existing stocks of Corning cable will be used in low risk / low volume areas.” (See Bad Bureaucrats File No/16)

Were the citizens of Australia entitled to be advised by the Australian government, before it sold off the Telstra network, that, e.g., the aforementioned optical fibre with CPC3 coating, supplied to Telecom/Telstra by Corning Inc (USA), was installed in their area? How many people in Australia have been forced to live with a subpar phone system, i.e., a known poor optical fibre that Telstra should NEVER have installed? How many businesses have gone up against the wall due to Telstra’s negligent conduct of knowingly laying their existing stocks of Corning cable in locations that Telstra believed were low-risk/low-volume areas?

All of this was known to the Telstra board when they negotiated the $400 million deal with Rupert Murdoch and Fox. During my arbitration case, I denied that there were any problems within Telstra's network. I even provided nine separate individual witness statements under oath, asserting that there were no ongoing telephone issues. This led arbitrator Dr Hughes, in his award dated May 11, 1995, to state that my phone faults had all been resolved by July 1994. However, evidence from absentjustice.com confirms that problems continued to affect the business at least until 2006, which was five years after the new owners purchased my business.

👉 The Vexatious Label — A Manufactured Smear

For years, government agencies and Telstra-aligned officials branded me as vexatious and my claims about Ericsson, Lane, and Telstra, as well as the arbitrator, as frivolous. It was a calculated move—designed not to reflect truth, but to discredit a whistleblower who refused to back down.

This label wasn’t born of evidence. It was born of self-preservation—a tactic used by those with a vested interest in concealing the abuse of Australia’s international arbitration process. The goal was simple: silence the messenger, bury the message.

Presiding over the two AAT hearings, Senior Member Mr G. D. Friedman addressed me directly in open court, in full view of two Australian Communications Media Authority (ACMA) government lawyers:

“Let me just say, I don’t consider you, personally, to be frivolous or vexatious – far from it. I suppose all that remains for me to say, Mr Smith, is that you obviously are very tenacious and persistent in pursuing the – not this matter before me, but the whole – the whole question of what you see as a grave injustice, and I can only applaud people who have persistence and the determination to see things through when they believe it’s important enough.”

This moment was more than personal vindication. It was judicial recognition of the legitimacy of my claims, my evidence, and my unwavering pursuit of justice.

Yet despite this, other agencies continued to weaponise the “vexatious” label—hoping to undermine my credibility and shield themselves from scrutiny. Their refusal to acknowledge Mr Friedman’s statement speaks volumes about the culture of denial that permeates institutional power.

This chapter lays bare the contrast between truth and reputation management, as well as between judicial integrity and bureaucratic deflection. It documents how the label of “vexatious” became a tool of suppression—and how, through persistence and documentation, I exposed it for what it truly was: a smear campaign against accountability.

(see Bad Bureaucrats File No/11 – Part One and File No/11 – Part Two)

“The Report, when commenting on the number of customers with COT-type problems, refers to a research study undertaken by Telecom at Austel’s request. The Report extrapolates from those results and infers that the number of customers so affected could be as high as 120 000. … (See Open Letter File No/11)

And the next day:

“In relation to point 4, you have agreed to withdraw the reference in the Report to the potential existence of 120,000 COT-type customers and replace it with a reference to the potential existence of “some hundreds” of COT-type customers” (See Open Letter File No/11)

Point 2.71 in AUSTEL’s April 1994 formal report notes:

“the number of Telecom customers experiencing COT type service difficulties and faults is substantially higher than Telecom’s original estimate of 50”.

It is nothing short of a treacherous betrayal for a government regulator to so drastically alter its findings, slashing the number of reported COT-type complaints from an astonishing 120,000 to a mere 50 or so. Such a flagrant misrepresentation constitutes a deep and sinister deception, undermining the very trust of the public it claims to serve. The fact that Rupert Murdoch and FOX are rewarded amidst these glaring Telstra telecommunications issues reveals a disturbing collusion, costing Australian citizens dearly—even leading some to bankruptcy and dragging them into numerous court cases—all due to the lies perpetuated by government bureaucrats. This manipulation not only defrauds the people but also casts a long shadow over the integrity of those in power.

These ongoing systemic telephone faults highlight the significant issues within Australia's copper network, as documented on absentjustice.com and in sources like Delimiter’s "Worst of the worst: Photos of Australia’s copper network | Delimiter.

23 June 2015: Had the arbitrator appointed to assess my arbitration claims correctly investigated ALL of my submitted evidence, it would have validated my claim as an ongoing problem, NOT a past problem, as his final award shows. It is clear from the following link→ Unions raise doubts over Telstra's copper network; workers using ... that when read in conjunction with Can We Fix The Can, which was released in March 1994, these copper-wire network faults have existed for more than 24 years.

9 November 2017: Sadly, many Australians in rural Australia can only access a second-rate NBN. This didn’t have to be the case: had the Australian government ensured that the arbitration process it endorsed to investigate the COT cases’ claims of ongoing telephone problems was conducted transparently, it could have used our evidence to start addressing the problems we uncovered in 1993/94. This news article https://theconversation.com/the-accc-investigation-into-the-nbn-will-be-useful-but-its-too-little-too-late-87095, again, shows that the COT Cases' claims of a copper wire-ailing network were more than valid.

28 April 2018: This ABC news article dated 28 April 2018 regarding the NBN see >NBN boss blames Government's reliance on copper for slow ... needs to be read in conjunction with my own story going back 20 1988 through to 2025, because had the arbitration lies told under oath by so many Telstra employees had not occurred then the government would have been in a better position to evaluate just how bad the copper-wire Customer Access Network (CAN) was just 7-years ago.

📘A Call to Examine the Machinery of Concealment

If you're visiting absentjustice.com and reflecting on the claims I’ve made about the actions of bureaucrats, public servants, and government agencies, I urge you to examine the following assertions closely. These are not mere grievances—they point to unlawful and corrupt practices designed to pervert the course of justice against the COT Cases. We were individuals who dared to challenge a government-owned corporation accused of theft, intimidation, and deliberate efforts to discredit anyone who stood in its way during the COT arbitrations.

Unravel the complex web of foreign bribery and insidious corrupt practices, including manipulating arbitration processes through bribed witnesses who shield the truth from the public eye. This narrative encompasses egregious acts of kleptocracy, deceitful foreign corruption programs and the troubling involvement of international consultants whose fraudulent reporting has enabled the unjust privatisation of government assets—assets that were ill-suited for sale in the first place.

After almost two decades, the British public and several British politicians have been saying that this matter is of public interest and should not be concealed (hidden) by the government. It is essential for England's interest that this matter be thoroughly investigated. Click here to watch the Australian television Channel 7 trailer for 'Mr Bates vs the Post Office', which went to air in Australia in February 2024. The British Post Office public servants knew that the Fujitsu Horizon computer software was responsible for the incorrect billing accounting system, as evidenced in this YouTube link: https://youtu.be/

MyhjuR5g1Mc.

Click here to watch Mr Bates vs the Post Office

The "secret email" newsletter will keep you informed about developments in the Post Office Horizon IT scandal.

To understand the broader implications of institutional betrayal, I strongly recommend exploring the Alan Bates website. His campaign to expose the British Post Office scandal has drawn widespread media attention. Numerous YouTube videos and detailed reports offer a sobering look at how systemic failures were concealed—just as Telstra buried its own computer software billing faults.

By studying Alan Bates’s story, the parallels become clear. Both cases reveal how powerful entities manipulated data, suppressed evidence, and targeted whistleblowers to protect their reputations. Whether it was Telstra’s cover-up of billing system flaws or the British Post Office’s concealment of Horizon’s defects, the pattern is unmistakable: truth was sacrificed to preserve institutional power.

As I approach my 82nd year, I am inspired to document my experiences with the convoluted Telstra arbitration issues and the various unscrupulous lawyers and forensic accountants who exploited the plight of the COT arbitrations for their own gain. This entire experience serves as a poignant reminder of the inner strength required to confront daunting obstacles and the relentless resilience needed to pursue justice, even in the face of overwhelming uncertainty and adversity. Through my writing, I hope to illuminate the complexities of our struggle and inspire others to stand firm against injustice.

In essence, a troubling disparity exists in the application of legal standards within the Australian business landscape, where individuals with strong connections to the government, such as Rupert Murdoch, are afforded different treatment compared to those who lack such privileges.

While I acknowledge the necessity of safeguarding Foxtel's substantial financial investment in its cable infrastructure, as well as the numerous hidden costs associated with the Murdochs' expansive media operations, I also wish to highlight my significant contributions. Over the years dedicated to building my business, I invested considerable resources into establishing a vibrant agency that served Melbourne, Ballarat, and Mount Gambier in South Australia. This agency was explicitly designed to manage incoming bookings for my Over Forties Single Club efficiently. This lively community hub offers a space for singles over forty to form connections and cultivate companionship. This initiative became a hallmark of community engagement, consistently generating between $6,000 and $7,000 each weekend—an impressive indicator of its popularity and the demand for social opportunities among this demographic.

This was not just a failure of oversight. It was complicity. A coordinated effort to protect the powerful and bury the truth. The watchdogs appointed to oversee the arbitrations—the so-called umpires—turned a blind eye. The arbitrator refused to act. The system was rigged from the start.

Helen saw it. She recoiled from it. And she wanted Rupert to see it too.

In July 1995, the Canadian Government recognised the urgent need to support my quest to expose the corrupt practices of Telstra, which had resorted to deceit, manipulation, and the use of falsified evidence to shield themselves from the rightful claims I had made.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

Moreover, it is critical to highlight that the correspondence from the Canadian Government included a disturbing exhibit that revealed Dr Hughes, not long after he closed my arbitration, was made aware that Telstra had intentionally leveraged a falsified BCI report to obstruct any investigation into my ongoing telephone issues (see Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2). Alarmingly, despite this revelation, Dr Hughes chose to turn a blind eye and refused to reopen the case. This decision came in stark contrast to his May 12, 1995, letter to the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), in which he acknowledged that the arbitration agreement he employed was woefully inadequate, allowing no time for a thorough examination of crucial technical reports, such as the one involving BCI.

A 1995 letter to the TIO stating that the arbitration agreement he had used in my arbitration did not allow sufficient time to investigate technical reports, such as the one attached here as Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2.

📘 Fabricated Evidence, International Silence

• Why did Telstra release documents proving AUSTEL relied on fundamentally flawed data?• Why did the Australian Government conceal these facts, knowing they contributed directly to the destruction of my business?• And why was I forced to travel to Canada to seek justice for a wrong committed on Australian soil?

• 1987: Transition from maritime life to land-based hospitality.• Purchase of Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, Victoria.• Initial excitement and vision for a thriving school holiday business.• Early signs of trouble: customers and suppliers unable to reach the camp by phone.• Realisation that the phone service was unreliable—crippling for a hospitality business.• Attempts to resolve the issue through Telstra (then Telecom) met with denial and delay.• Mounting business losses and emotional toll.

• Discovery that other rural business owners were facing similar telecommunications failures.• Formation of the Casualties of Telecom (COT) group—united by shared injustice.• Initial optimism: calls for a Senate inquiry into Telecom’s conduct.• Government offers arbitration as an alternative to investigation.• Acceptance of arbitration in good faith, believing technical faults would be addressed.• Early signs of deception: promised documents withheld, technical faults ignored.

• Arbitration begins under the guise of fairness and resolution.• Telstra’s failure to provide critical documents despite legal obligations.• Claimants discover their fax lines are being intercepted—illegal surveillance during arbitration.• Evidence mounts: missing faxes, dual time stamps, unexplained delays.• Arbitrator refuses to allow resubmission of lost documents.

• Attempts to challenge the arbitration outcome blocked by confidentiality clauses.• Legal gag orders prevent public disclosure of misconduct.• FOI requests were launched to obtain the missing documents.• Government departments stonewall or heavily redact responses.• Emotional and financial toll on claimants intensifies.• Growing suspicion of collusion between Telstra, government regulators, and legal overseers.

• Evidence emerges of systemic corruption: Telstra’s internal knowledge of faults, concealed from claimants.• Senate Hansard records reveal Telstra’s board knowingly entered into contracts it couldn’t fulfill.• Revelation of Rupert Murdoch’s $400 million compensation deal with Telstra.• Helen Handbury’s reaction: horror at the scale of injustice and betrayal.• Contrast between Murdoch’s payout and the suffering of ordinary Australians.• Telstra’s dual role: sabotaging claimants while rewarding the powerful.• The machinery of collusion exposed—government, corporation, and legal system intertwined.

• During the early stages of the COT arbitrations, the claimants’ legal representatives reviewed and accepted an arbitration agreement that included a $250 million liability cap—designed to protect claimants from excessive exposure and ensure accountability from those overseeing the process.• After this agreement was accepted, the arbitrator—without notifying the claimants or their lawyers—allowed the liability caps to be quietly removed. This covert alteration stripped away a critical safeguard, leaving claimants vulnerable and removing any meaningful legal recourse against misconduct.• The removal of these caps was not disclosed transparently. It was buried beneath layers of bureaucratic silence and legal obfuscation.• Those who administered the arbitration—including the arbitrator and consultants—have since weaponized the confidentiality clauses embedded in the agreement. These clauses are now being used to suppress scrutiny, silence dissent, and prevent any challenge to the conduct of the arbitration itself.• The result? A system where the very individuals responsible for overseeing justice are shielded from accountability. The consultants who mishandled evidence, obstructed claims, and enabled Telstra’s manipulation cannot be sued for misconduct—because the protections were removed in secret.• This manoeuvre was not just unethical. It was strategic. It ensured that the machinery of arbitration could operate with impunity, free from consequence, while claimants were left to suffer in silence.

⚓ The Beginning of the Saga

It began in late 1987 when my wife Faye and I bought a small accommodation business perched high above Cape Bridgewater, near Portland on Victoria’s southwest coast. The Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp had previously operated as a school camp. We intended to transform it into a venue for social clubs, family groups, and schools.

The camp was a phone-dependent concern. Being in a remote area, the telephone was the primary means of access for city-based clients. Our mistake was failing to investigate the telephone system thoroughly before making the purchase. The business was connected to a phone exchange installed over 30 years earlier, designed for “low-call-rate” areas. This antiquated, unstaffed exchange had only eight lines and was never intended to handle the volume of calls from a growing population and seasonal holidaymakers.

In blissful ignorance, we sold our Melbourne home, and I took early retirement benefits to raise the funds for what we believed would be an exciting new venture.

🧭 A Life Built for Hospitality

I knew I could run this business. At fifteen, I went to sea as a steward on English passenger/cargo ships. In 1963, I jumped ship in Melbourne and worked as an assistant chef in some of the city's elite hotels. Two years later, at twenty, I joined the Australian Merchant Navy. By 1975, I’d served as a chef on many Australian and overseas cargo ships.

Faye and I were married in Melbourne in 1969. I freelanced in catering and worked on tugboats while studying hotel/motel management. I’d already managed one hotel/motel, pulling it out of receivership and preparing it for release. By 1987, at 44, I had gained the experience and confidence to transform a simple school camp into a successful, multifaceted concern.

📞 Marketing Meets Silence

I personally visited nearly 150 schools and shires to promote the camp. In February 1988, we printed and distributed 2,000 colour brochures. Then we waited for the phone to ring. It didn’t. Not even a modest 1% inquiry rate.

By April, we suspected the problem lay with the telephone service. People asked why we never answered our phone or suggested we install an answering machine — which we had. Even after replacing it, complaints continued. Callers reported extended periods of engaged signals.

Then came the dropouts. Calls would go dead mid-conversation. If the caller hadn’t given contact details and didn’t ring back, we lost the lead. Between April 1988 and January 1989, Telstra received nine complaints from me, along with several letters. The typical response to my 1100 call was a promise to check the line. Occasionally, a technician was sent. The verdict? “No fault found.” But the problems persisted.

🕵️♂️ Digging Deeper

Eventually, we learned the previous owner had suffered the same issues and had complained — also unsuccessfully. In 1988, I began building a case against Telstra and obtained documents through the Freedom of Information Act. One, titled Telstra Confidential: Difficult Network Faults — PCM Multiplex Report, included a subheading: “5.5 Portland — Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp.” Telstra had been aware of the faults since early 1987.

Harry, our neighbour, sympathised. His daughter, calling from Colac, often struggled to get through. Fred Fairthorn, former owner of Tom the Cheap grocery chain, had similar problems. He said, “But what can you expect from Telstra when we’re in the bush?” I expected better. We were promised better.

📉 Decline and Doubt

We encouraged people to write, but the telephone culture was entrenched. People wanted immediate responses. As bookings dwindled, I began to question my decision to move to Cape Bridgewater—and to ask Faye to sell our family home to satisfy my ambitions. It wasn’t the fun I’d anticipated. I operated in a state of constant anger — a very unamusing Basil Fawlty.

We toured South Australia to promote the camp through the Wimmera region. Responses were few. Was the phone to blame? How could we be sure? The uncertainty itself was stressful.

📵 The Message That Killed My Business

Sometimes the culprit was obvious. On a shopping trip to Portland, I realised I’d left the meat order list at home. I called from a public phone box — only to hear a recorded message: “The number you have called is not connected.” I tried again. Same message. Telstra’s fault centre said they’d investigate. Later, I called again and got an engaged signal. I bought what I could remember and hoped for the best. When I got home, the phone hadn’t rung once.

Anyone who uses a phone has heard the recorded voice announcement (RVA):

“The number you have called is not connected or has been changed. Please check the number before calling again. You have not been charged for this call.”

This incorrect message was the one most callers reached when trying to contact the camp. Telstra never acknowledged it. But in 1994, among a trove of FOI documents, I found a Telstra internal memo stating:

“This message tends to give the caller the impression that the business they are calling has ceased trading, and they should try another trader.”

✍️ Chapter Two: No Fault Found

No Fault Found, or an RVA fault, is a deceptive mechanism implemented by Telstra. This Recorded Voice Answering message informs unsuspecting callers that the number they are dialling is disconnected from Telstra’s service, when in reality, they are connected. This insidious misrepresentation has allowed Telstra to evade accountability for decades.

In a chilling memo, Telstra acknowledged the urgent need for “a very basic review of all our RVA messages and how they are applied.” The memo ominously suggested, “I am certain that as we begin to probe deeper, we will uncover a myriad of network scenarios where inappropriate RVAs are thriving.” This admission hints at a dark web of manipulation hiding in plain sight, obscuring the truth from countless customers.

It seems the “not connected” RVA triggered whenever the lines in or out of Cape Bridgewater were congested — which, given how few lines there were, was often.

For a newly established business like ours, this was catastrophic. Yet, despite internal memos acknowledging serious faults, Telstra never admitted to any existing. My continued complaints branded me a nuisance caller. This was rural Australia, and I was expected to tolerate poor service — not that Telstra ever admitted it was poor. Every technician’s verdict: “No fault found.”

📞 The Weight of Uncertainty

The frustration was immense. Was this just general rural service compounded by congestion on an antiquated exchange? Ours was the only accommodation business in Cape Bridgewater. We relied on the phone more than most. But if there was a specific fault, why wasn’t it being found?

By mid-1989, the business was in trouble. We began selling shares to cover operating costs — just 15 months after taking over the business. Instead of reducing the mortgage, we were selling assets. I felt like a failure. Neither of us could lift the other’s spirits.

📵 Silence in the City

I launched another round of city marketing. We both went. Maybe it was masochism that made me ring the camp’s answering machine via remote access — hoping to respond to messages promptly. All I got was the dreaded recording:

“The number you are calling is not connected or has been changed…”

On the way home, just outside Geelong, I tried again from a phone box. This time, the line was engaged. Maybe someone was leaving a message, I thought. Ever hopeful.

There were no messages. And no answers. How many calls had we lost while we were away? How many prospective clients gave up because they thought we’d ceased trading? Anger and frustration simmered just beneath the surface.

💔 Collapse