Kangaroo Court - Absent Justice

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

― Maya Angelou

Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers. Government corruption, fraudulent reporting, and misleading journalistic practices, including deceptive news reporting and the dissemination of false information, are unacceptable in a Western nation such as Australia, which asserts its commitment to the rule of law. Such actions undermine the integrity of governance and the principles of transparent and responsible journalism.

INTRODUCTION

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government held complete ownership of the nation’s telephone network and communications carrier, known as Telecom, which is now operating privately under the name Telstra. During this time, Telecom maintained a government-sanctioned monopoly over communications services, allowing the infrastructure to deteriorate significantly and leaving consumers frustrated.

When four small business owners grappled with severe and chronic communication issues, they turned to arbitration, guided by the belief that the government would compel Telstra to resolve their ongoing telephone troubles. However, they quickly discovered that the arbitration process was deeply flawed. The arbitrator failed to insist that Telstra explain the persistent telephone and faxing problems that continued to disrupt the COT Cases business. This drawn-out arbitration lasted thirteen months to an astonishing three years, leaving the business owners in a torturous limbo.

By the time the process was nearing its end, the number of COT Cases had swelled to twenty-one. More business owners, eager for resolution and unaware of the public nature of these procedures, sought to join as arbitration claimants. The initial four had already invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in mounting their complex and legally intricate claims against Telstra's legal team, resulting in a costly battle.

In a display of overwhelming legal might, forty-seven of Australia’s most prominent law firms, which had long been on retainer, were unleashed to challenge and undermine the COT Cases. Telstra, demonstrating its willingness to spare no expense, poured over twenty million dollars into fighting claims that, when all costs were aggregated, were worth less than half that amount. The situation painted a stark picture of David versus Goliath, with the small business owners caught in a relentless struggle against a corporate giant.

My efforts to bring this significant discrepancy to the government's attention came two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, but I was met with indifference. The government's lack of interest in contacting BCI in Canada was disheartening. Instead, the Canadian Government recommended that I write directly to Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) from Australia for guidance and support, leaving me feeling heartened that someone cared.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

The Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On 29 June 1995, the Canadian government appeared concerned that Telstra's lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now known as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne), provided false Bell Canada International Inc. tests. These tests were meant for Mr Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, to review before he travelled to Portland to assess my mental health during the arbitration.

I am convinced that the submission of fraudulent test call records from Bell Canada International Inc. concerning Cape Bridgewater, which were presented to Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, during my arbitration, aimed to mislead Mr. Joblin into believing that I was mentally unstable. This deliberate manipulation of information misrepresented my state of mind and provoked significant concern from the Canadian government. Please refer to my detailed explanation below for a more comprehensive understanding of this matter.

In a troubling turn, Telstra and its legal representatives, Freehills Hollingdale & Page (now operating as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne), presented a fabricated Bell Canada International (BCI) report to Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, to read before Mr Joblin assessed my mental state. This misleading BCI document claimed that 15,590 test calls were successfully transmitted over four to five hours spanning five days, from November 4 to November 9, 1993, to my local telephone exchange at Cape Bridgewater. During my arbitration, this spurious information concerning my telephone claims was presented to Ian Joblin, who was part of Telstra's arbitration defence unit.

By utilizing these deceptive BCI tests, Freehills Hollingdale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne aimed to create the impression that Ian Joblin would conclude I must be suffering from paranoia regarding my alleged phone issues. They implied that anyone of sound mind would not assert they were experiencing phone problems when, according to the fabricated BCI report, the 15,590 test calls were supposedly transmitted without incident. This manipulation of information raises serious concerns about the integrity of their defence and the implications for my claims.

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehill Hollingdale & Page, signed the witness statement without Ian Joblin (the psychologist) signature being on the witness statement when presented to the arbitrator hearing my case is unlawful enough; however, with that said, the fact John Pinnock, administrator to my arbitration as well as the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman has in 2025, still not provided Telstra's official response concerning this dreadful conduct by Mautice Wayne Condon of Freehills Hollingdale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne shows how much power Telstra lawyers have over the legal system of arbitration in Australia.

On 21 March 1997, twenty-two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to my arbitration), wrote to Telstra's Ted Benjamin (refer to File 596 Exhibits AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) asking:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin .

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?"

As of 2025, I am still awaiting a copy of Ted Benjamin's comprehensive explanation regarding John Pinnock’s letter dated March 21, 1997. This clarification could have shed light on the circumstances surrounding a crucial witness statement and might have provided me with valid grounds to appeal my arbitration decision. The delay in obtaining this information is exceedingly concerning.

I have reason to question whether the BCI's factual findings were improperly removed and subsequently provided to Mr. Joblin, then extracted from his witness statements. Dr. Joblin himself criticized Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now operating as ) for neglecting to review the BCI documents before presenting evidence related to Ian Joblin. This situation raises significant questions that should have been thoroughly examined, enabling me to leverage materials, such as this unsigned witness statement, as essential tools to pursue a fair appeal.

The conduct of Freehill Hollingdale & Page/ Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne is deeply troubling. They not only supplied misleading BCI information to Ian Joblin but also appeared to manipulate his statements by omitting them or altering their content. Further complicating matters, they submitted an unsigned witness statement to the arbitration process, despite the government previously advising Telstra that Freehill Hollingdale & Page should not be utilized against the COT cases in any of their future dealings. This directive was clearly outlined in point 40 Prologue Evidence File No/2. However, despite this explicit warning, Telstra chose to engage the services of Freehill Hollingdale & Page./ Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne. This critical information could have been instrumental in my efforts to win an appeal or amend my claims substantively.

BELL CANADA INTERNATIONAL BCI - Cape Bridgewater tests.

Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) employed the highly regarded CCS7 monitoring equipment to generate an astonishing number of calls. However, the nearest telephone exchange equipped to handle this advanced CCS7 technology was 112 kilometers from my business location. This raises the question: where did the staggering 15,590 test calls ultimately end up? As you delve into this story, you'll uncover a troubling detail — Telstra audaciously contaminated the collected TF200 telephone by pouring wet and sticky beer residue into it after those phones departed from the COT Cases businesses. Adding to this bizarre scenario, Telstra sought to label other COT Cases members as mentally unstable, as evidenced by my narrative. This corporation has remained unchanged; the current Corporate Secretary, Sue Laver, holds the key to revealing the truth about the BCI (false test results) provided to Ian Joblin. All she needs to do to clarify matters is publicly dismiss my claims as frivolous in a media release, along with the evidence that my claims are false.

In 1997, during the government-endorsed mediation process, Sandra Wolfe, a third COT case, encountered significant injustices and documentation issues. Notably, a warrant was executed against her under the Queensland Mental Health Act (see pages 82 to 88, Introduction File No/9), with the potential consequence of her institutionalization. Telstra and its legal representatives sought to exploit the Queensland Mental Health Act as a recourse against the COT Cases in the event of their inability to prevail through conventional means. Senator Chris Schacht diligently addressed this matter in the Senate, seeking clarification from Telstra by stating:

“No, when the warrant was issued and the names of these employees were on it, you are telling us that it was coincidental that they were Telstra employees.” (page - 87)

Why has this Queensland Mental Health warrant matter never been transparently investigated and a finding made by the government communications regulator?:

Sandra Wolfe, an 84-year-old cancer patient, is enduring severe challenges while striving to seek resolution for her ongoing concerns. Upon reviewing her recent correspondence, it becomes evident that a notable lack of transparency has marked her experience with the Telstra FOI/Mental Health Act issue. The actions of Telstra and its arbitration and mediation legal representatives towards the COT Cases portray a concerning pattern. This is exemplified by the unfortunate outcomes experienced by many COT Cases, including fatalities and ongoing distress. My health struggles, including a second heart attack in 2018, necessitated an extended hospitalization, underscoring the urgency with which these matters must be addressed. It is my sincere aspiration that my forthcoming publication will serve to expose the egregious conduct of Telstra, a corporation that warrants closer scrutiny.

Regrettably, the Senate only chose to investigate five of the twenty-one COT processes. These five cases were designated as litmus tests, crucial for understanding the broader issues at hand. Meanwhile, the remaining sixteen cases were informed that their individual concerns would be collectively assessed as a group, contingent upon the outcomes of the five litmus test cases. If those initial cases successfully demonstrated their claims against the flawed government-endorsed processes, it could pave the way for a more thorough examination of the broader set of concerns.

See below what six Senators collectively stated after investigating the five aforementioned litmus test cases.

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Regrettably, because my case had been settled three years earlier, I and several other COT Cases could not take advantage of this investigation's valuable insights or recommendations. Pursuing an appeal of my arbitration decision would have incurred significant financial costs that I could not afford as shown in an injustice for the remaining 16 Australian citizens.

The Senate investigation statement demonstrates that the COT Cases were promised essential documents prior to being compelled into government-endorsed arbitrations. This occurred without the crucial documents we were entitled to, including the Telstra telephone exchange Logbook, which should have been provided through the agreed discovery process or under the Freedom of Information (FOI Act).

The arbitrator appointed to oversee the proceedings dismissed many claims made by the members of the Casualties of Telstra (COT) and allowed Telstra to take control of the arbitration process itself. This created an environment where Telstra could operate with impunity, even as it engaged in serious misconduct throughout the hearings. Despite the overwhelming evidence of wrongdoing, neither the Australian government nor the Australian Federal Police (AFP) has taken action to hold Telstra or any other involved parties accountable for their deceptive practices.

On 26 September 1997, after most of the arbitrations had been concluded, including mine, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, John Pinnock, who took over from Warwick Smith who was the administrator to the arbitrations, formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

No amendment is attached to any agreement, signed by the COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those particular arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure – and neither was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide or deny the COT Cases the reason our requested telephone log books from the relevant telephone exchanges that serviced our businesses were withheld from us?

How can the arbitrator—who had no control over the arbitration proceedings—continue concealing the reasons for refusing access to the telephone exchange logbooks that would prove or disprove each COT Case assertion in their arbitration submissions? These logbooks were essential records during the COT arbitrations because they meticulously document every daily fault reported by businesses and residences relying on Telstra telephone exchanges across multiple locations under scrutiny in Australia. This information was crucial for evaluating the scope of the issues under investigation during the arbitration process and, therefore, understanding the impact on each affected party. The lack of transparency regarding this denial raises serious concerns about the integrity of the arbitration and the ability to assess the reliability of the telecommunications services in question effectively.

The complexities surrounding the COT cases and their arbitration are vast and intricate. In establishing this website, we realized that the only way to present the information clearly was to categorize the various issues under distinct headings (please refer to the menu bar above). As we continued to develop the site, we uncovered numerous interconnections among the issues that spanned multiple events, revealing a tapestry of corruption and illegal activities. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the severe misconduct that occurred during and after the arbitrations, some events are detailed in several sections of the website, ensuring a thorough exploration of this troubling saga.

Whistleblowing in Australia, along with the protective legislation that surrounds it, is often clouded by misconceptions, particularly regarding the crucial role that reporting misconduct plays in promoting accountability and integrity. If the COT Cases had been aware of the incoming arbitrator, Dr. Hughes AO, and his prior history of favoring Telstra—the corporate giant embroiled in their legal disputes—they would have approached their circumstances with far greater caution and scrutiny. Dr. Hughes AO had previously engaged in unethical behavior by concealing vital information from a client during a pivotal Federal Court action, severely compromising the client's ability to negotiate a more advantageous out-of-court settlement (as detailed in Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest - File 567 GS-CAV 522 to 580). This deliberate withholding of information distorted the landscape of the legal proceedings and significantly influenced the Federal Court's findings. Armed with this critical knowledge, the COT Cases would have decisively rejected Dr. Hughes AO as their arbitrator three years later in the subsequent arbitration against Telstra. Unfortunately, history repeated itself during this arbitration process, where Dr. Hughes AO failed to disclose significant relevant Telstra-related information, ultimately obstructing the pursuit of justice and leaving the claimants at a profound disadvantage.

Had Dr. Hughes AO taken the initiative to inform the COT Cases, their legal representatives, and several government ministers who showed interest in the COT Cases that he had previously offered legal counsel regarding similar telephone issues during Mr Schorer's previous Federal Court Action with Telstra as the defendants, a crucial dialogue could have occurred before the proceedings. This would have facilitated a meeting among all relevant parties, enabling us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between Dr. Hughes and Graham Schorer, who, in 1994, was the spokesperson for the COT Cases.

Thorough research into this matter prior to accepting Dr. Hughes as the arbitrator could have unearthed pertinent legal documents. These documents would likely have revealed that Dr. Hughes AO and the Partnership concealed important government correspondence regarding the serious deficiencies of the telephone exchange linked to Mr. Schorer's business.

Armed with this vital information, the COT Cases, myself included, would have had compelling reasons to doubt Dr. Hughes's ability to act as an impartial arbitrator, leading us to reject his candidacy outright.

In the twelve chapters and mini-stories available on absentjustice.com, we illuminate the discrimination faced by a vital segment of the business community. This discrimination manifests as preferential treatment for large corporations that provide kickbacks to government bureaucrats, allowing these injustices to persist through 2025. It is time for individuals to rise and spotlight the issues presented in my narratives, alongside the accompanying 3,360 exhibit files that empower us by supporting the claims made in the twelve chapters and all significant statements related to the theme of absent justice.

Each chapter has been meticulously edited for clarity, and we are dedicated to continuously expanding and refining the narrative as the story unfolds. By offering these chapters individually, we provide readers with an accessible gateway to the intricate and multifaceted issues surrounding arbitration practices in Australia. Exploring one, two, or even three chapters will uncover engaging insights that set the stage for a deeper understanding before immersing yourself in the complete story, which encompasses 67,520 words. This structure allows readers to navigate the complexities of the subject matter at their own pace, ensuring a rich and fulfilling reading experience.

You can access my book 'Absent Justice' here → Order Now—it's Free. It presents a compelling narrative that addresses critical societal issues related to justice and equity within Australia's arbitration and mediation processes. If you see the value in the research and evidence behind this important work, consider supporting Transparency International Australia! Your donation will help raise awareness about the injustices that impact our democracy.

Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers. Read about the corruption within the government bureaucracy that plagued the COT arbitrations. Uncover who committed these horrendous crimes and where they sit in Australia’s Establishment and the legal system that allowed these injustices to occur!

Explore the insidious corruption that has seeped deep into the fabric of Australia’s government bureaucracy, casting a dark shadow over the arbitration and mediation system. This corruption is so pervasive and shocking that those reading this part of this true story may be overwhelmed with disgust and disbelief. How has this troubling situation come to fruition?

Who holds the power and influence over the Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators of Australia (IAMA) to halt an investigation and refuse to return the evidence that the IAMA initially requested from the individual they agreed to investigate, which confirmed the government-appointed arbitrator only investigate (eleven per cent (11%) of my legally submitted claim documents? Why has the IAMA declined to return the evidence I provided them at their request over five months? Refer to Chapter 11 - The eleventh remedy pursued.

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government wholly owned Australia’s telephone network and the communications carrier, Telecom (now privatised and known as Telstra). Telecom monopolised communications and allowed the network to deteriorate into disrepair. When sixteen small business owners faced significant communication challenges, they stepped forward to seek justice through arbitration with Telstra. Unfortunately, the arbitrations proved to be a mere facade: the appointed arbitrator allowed Telstra to minimize the claims of the sixteen and even permitted the carrier to dominate the process. Despite the serious offences committed by Telstra during these arbitrations, the Australian government struggled to hold them, or the other involved entities, accountable.

Six months before the arbitrations began, four of the sixteen claimants, including myself, boldly requested access to our local telephone exchange logbooks under the Freedom of Information Act (1984 FOI Act). We were assured that the arbitrator would provide these logbooks once we signed our arbitration agreements. However, this crucial document was never made available to claimants.

The Adverse Findings issued by AUSTEL, see points 1 to 212 in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, unequivocally demonstrate that the logbook referenced by the government to support its unfavourable conclusions about Telstra was sourced from the Portland/Cape Bridgewater telephone exchange logbook. This logbook, which meticulously records telephone activity and technical performance, played a pivotal role in shaping the government’s stance, highlighting its importance as a critical piece of evidence in the ongoing scrutiny of Telstra’s operations.

Had the COT Cases been told before they signed their arbitration agreements that the arbitrator would have no control over the arbitration because the process would be conducted 'entirely' outside the agreed procedures, I, for one, would have stayed in my Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP) signed by Telstra on 18 November 1993 and the four COT Cases on 23 November 1993.

I highly recommend you check out the link “My Story Warts and All.” Like many other mini-reports in our 'Evidence File-1', this content will be refined and re-edited before integration.

On 26 September 1997, after most of the arbitrations had been concluded, including mine, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, John Pinnock, who took over from Warwick Smith, formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

No amendment is attached to any agreement, signed by the COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those particular arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure – and neither was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide or deny the COT Cases the reason our requested telephone log books from the relevant telephone exchanges that serviced our businesses were withheld from us?

How can the arbitrator—who had no control over the arbitration proceedings—continue concealing the reasons for refusing access to the telephone exchange logbooks that would prove or disprove each COT Case assertion in their arbitration submissions? These logbooks were essential records during the COT arbitrations because they meticulously document every daily fault reported by businesses and residences relying on Telstra telephone exchanges across multiple locations under scrutiny in Australia. This information was crucial for evaluating the scope of the issues under investigation during the arbitration process and, therefore, understanding the impact on each affected party. The lack of transparency regarding this denial raises serious concerns about the integrity of the arbitration and the ability to assess the reliability of the telecommunications services in question effectively.

On November 11, 1994, John Wynack, the Director of Investigations for the Commonwealth Ombudsman, sent a compelling letter to Frank Blount, the CEO of Telstra. In this letter, Whynack demanded a thorough explanation for the numerous requested Freedom of Information (FOI) documents categorized with specific data periods relevant to my claim. Instead of complicating Telstra's search process, they only needed to access the designated time frame. Among these sought-after documents was a crucial extract from Telstra's Portland/Cape Bridgewater logbook, which spanned the significant months from June 1993 to March 1994 (Refer to File 20 - AS-CAV Exhibit 1 to 47)

How can you effectively publish a detailed and truthful account of the troubling events that unfolded during various Australian government-endorsed arbitrations while avoiding the direct naming of the individuals involved? In our Stop Press section below, we have only mentioned the relevant government regulator, purposefully omitting the identities of the public servants who clandestinely shared privileged information with the government-owned telecommunications carrier—the defendant. These same officials also concealed crucial documentation from the claimants, who happened to be fellow Australian citizens.

What strategies can you employ to convey a narrative so astonishing that your editor insists on an increasing volume of evidence to substantiate your claims? She is steadfast in her requirement for undeniable proof, refusing to edit your seemingly implausible assertions without verification.

How do you unearth and illustrate the troubling fact that the defendants in the arbitration process—the telecommunications carrier once owned by the government—utilized equipment connected to their expansive network to intercept and manipulate faxed materials originating from your office? They stored these documents without your knowledge or consent, later redirecting them to their intended destinations. Were the defendants leveraging this intercepted information to fortify their defence in arbitration and, as a result, diminish the chances of the claimants?

What can be said about the extent of this hacking? How many other Australian arbitration processes have fallen victim to similar invasive tactics? Is this form of electronic eavesdropping—hacking into confidential documents—still a pervasive issue today in legitimate Australian arbitrations? In January 1999, the arbitration claimants presented a compelling report to the Australian government, detailing how confidential, arbitration-related documents were surreptitiously and illegally intercepted before they could reach their designated destinations. In my situation, despite the arbitrator's secretary confirming that six of my faxed claim documents never made it to the arbitrator's office, I was left without the opportunity to resubmit this vital material for assessment. Records from my fax account verify that I dialled the correct number on all six occasions.

Moreover, one of the two technical consultants who attested to the authenticity of their findings in that report on December 17, 2014, reached out to me, affirming: "I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had, at some stage, been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted. Dual time stamps substantiated this on the faxes."

HELEN HANDBURY - Sister of Rupert Murdoch

I found myself grappling with a heavy reluctance to disclose to Helen that Rupert Murdoch was not only aware of but potentially complicit in Telstra's unethical practices. The implications of this revelation weighed on me, especially considering the enormous sum of $400 million depicted in the image below. If this amount were indeed channeled to FOX, it would represent a significant betrayal to every Australian citizen. Many of these individuals, struggling to maintain their livelihoods, have already endured the financial strain of covering their own arbitration and mediation costs just to secure a reliable phone service—an essential lifeline for their telephone-dependent businesses. This situation raises critical questions about accountability and fairness in an industry that should prioritize ethical standards. For those interested in exploring this issue further, I encourage you to refer to point 10 on pages 5164 and 5165 in the SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia → click below.

Hover your cursor/mouse over the following image →

In 1999, during a pivotal moment in my writing journey, I shared a draft of my story with Helen Handbury, the sister of media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Upon reading it, she was taken aback by the shocking denial of natural justice that we, the COT Cases, had been subjected to for far too long. Helen had visited my holiday camp twice, and her sincere concern echoed in her words when she said, “I will get Rupert to have it published; he will be shocked.” Her frankness revealed her deep empathy for our plight.

A particular aspect of my narrative that Helen struggled to grasp was the overwhelming evidence I had meticulously gathered regarding the illegal fax-hacking that had infiltrated my life. This insidious activity continued until Helen’s second visit. In 1999, the global scandal concerning the News of the World and the issues surrounding her brother had not yet erupted into public consciousness. I later provided substantial evidence to the Australian Federal Police, revealing that illegal interference with faxes during various arbitrations—of which I was an active claimant—began in 1994. The alarming information I disclosed to Helen indicated that this troubling fax hacking was still affecting my business premises in 1999, four years after my arbitration was meant to have resolved these grave matters.

It’s worth noting that 1999 represents when the world was still oblivious to the upcoming hacking scandal involving the News of the World. In my draft manuscript, which I provided Helen Handbury, was an attached letter to Warwick Smith, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (the administrator of the arbitrations), who secretly, in concert with Dr Hughes, allowed Telstra's lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now rebranded as Herbert Smith Freehills) to draft the arbitration agreement instead of an interdependent lawyer as the government and COT Cases were assured would be used. The government had already written to Telstra on 5 October 1993 (see point 40 Prologue Evidence File No/2) that the government would be more than a little concerned if Freehill had any involvement in the arbitrations. And here was the administrator and arbitrator of the process, allowing Telstra to dictate in the arbitration agreement how the process was to be conducted. The fact that the arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, had sent this on 12 May 1995, the day after he had deliberated on my arbitration damning the same Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne) agreement as not credible but used it anyway shows how unethical the COT Cases arbitrations were conducted.

To say this set of circumstances upset Helen Handbury is an understated. Helen was horrified.

Fax Screening / Hacking Example Only

Interception of this 12 May 1995 letter by a secondary fax machine:

Whoever had access to Telstra’s network, and therefore the TIO’s office service lines, knew – during the designated appeal time of my arbitration – that my arbitration was conducted using a set of rules (arbitration agreement) that the arbitrator declared not credible. There are three fax identification lines across the top of the second page of this 12 May 1995 letter:

- The third line down from the top of the page (i.e. the bottom line) shows that the document was first faxed from the arbitrator’s office on 12-5-95, at 2:41 pm to the Melbourne office of the TIO – 61 3 277 8797;

- The middle line indicates that it was faxed on the same day, one hour later, at 15:40, from the TIO’s fax number, followed by the words “TIO LTD”.

- The top line, however, begins with the words “Fax from” followed by the correct fax number for the TIO’s office (visible.

Consider the order of the time stamps. The top line is the second sending of the document at 14:50, nine minutes after the fax from the arbitrator’s office; therefore, between the TIO’s office receiving the first fax, which was sent at 2.41 pm (14:41), and sending it on at 15:40, to his home, the fax was also re-sent at 14:50. In other words, the document sent nine minutes after the letter reached the TIO office was intercepted.

The fax imprint across the top of this letter is the same as the fax imprint described in the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), which states:

“We canvassed examples, which we are advised are a representative group, of this phenomena .

“They show that

- the header strip of various faxes is being altered

- the header strip of various faxes was changed or semi overwritten.

- In all cases the replacement header type is the same.

- The sending parties all have a common interest and that is COT.

- Some faxes have originated from organisations such as the Commonwealth Ombudsman office.

- The modified type face of the header could not have been generated by the large number of machines canvassed, making it foreign to any of the sending services.”

The fax imprint across the top of this letter dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

The evidence within this report Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) also indicated that one of my faxes sent to Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was similarly intercepted, i.e.,

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

One of the two technical consultants who verified the accuracy of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

An accountant deeply involved with the COT Cases and a key constituent of The Hon. Peter Costello, Federal Treasurer, brought to light the substantial sums of money that Telstra employees reportedly embezzled from the public purse, as shown on pages 5163 to 5169 in Australia's Government SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia.

The Australian Federal Police were actively investigating this matter at the time. They also looked into my phone and fax interception issues; at the same time, they were examining Telstra's thieving from the government coffers. I confidently question whether the interception of my faxed letter to The Hon. Peter Costello was connected to this embezzlement. It raises an important point: is this why so many of my arbitration-related claim documents failed to reach the arbitrator's office?

The embezzlement of public funds by Telstra employees and the complicit board of directors, who knowingly allowed millions of dollars in erroneous customer charges to inflate Telstra's value during its privatization, constitutes fraud against unwitting shareholders. Shareholders were unaware that a significant portion of Telstra's profits came from overcharging its customers for over six years.

The link to Kangaroo Court, https://shorturl.at/JnQx2, shows ongoing misappropriation of government funds in 2024 and government cover-ups during the Afghanistan War, as https://shorturl.at/HDxU9 shows. These cover-ups of government issues are documented here as an 'example only' to show that when significant daily problems are not investigated transparently, they can destroy the very fabric of our democratic system of justice.

I am focusing on the latest 2024 issue concerning the Afghanistan War: https://shorturl.at/HDxU9. It highlights a critical issue: government public servants frequently engage in cover-ups, choosing to ignore matters they believe are better left unaddressed. This behaviour is not a new phenomenon; it mirrors the government's actions during the Vietnam War and the controversial China wheat deals—issues that I, along with others, brought to the government's attention during that tumultuous period.

It is essential to draw connections between these two significant wars, as both had far-reaching consequences for the well-being of countless individuals, including many who never took up arms. The fallout from these conflicts has vividly illustrated the presence of government corruption, and this is why I believe it is crucial to link these historical events with the corruption issues that arose during the Telstra-endorsed arbitrations. This connection is not just about historical accountability; it is about recognizing patterns of behaviour that continue to affect governance and public trust, which are key points of the ongoing COT story.

Before we delve into our narrative, we invite visitors to examine our Evidence File-1 and Evidence File-2 carefully. These meticulously compiled files contain extensive documentation that provides a solid foundation for our story and the other related COT narratives currently being developed.

Within these files, you will find a plethora of evidence that sheds light on the real-life experiences of twenty-one courageous Australians. These individuals faced significant challenges as they bravely stood up against the misconduct and oppressive practices of the Telstra Corporation, a struggle that spanned from 1988 to at least 2009.

Government Corruption and its many corrupt activities, including bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power, have begun to permeate many courts and justice institutions worldwide. In jurisdictions where such corruption is commonplace, marginalized and vulnerable populations often find themselves with limited access to justice. Meanwhile, those who are wealthy and powerful exploit and manipulate entire justice systems for their benefit, often at the expense of the public good and fair legal processes, as I have shown below in both Chapter 7-Vietnam Vietcong and the Australia–East Timor spying scandal.

The Secret State

On 26 September 2021, Bernard Collaery, Former Attorney-General of the Australian Capital Territory (under the heading) The Secret State, The Rule of Law & Whistleblowers, at point 7 of his 12-page paper, noted:

"On some significant issues the Australian Parliament has ceased to be a place of effective lawmaking by the people, for the people. It has become commonplace for Parliamentarians to see a marathon superannuated career out with ideals sacrificed for ambition."

Perhaps the best way to expose this part of the COT story is to use the Australia–East Timor spying scandal, which began in 2004 when an electronic covert listening device was clandestinely planted in a room adjacent to East Timor (Timor-Leste) Prime Minister's Office at Dili, to covertly obtain information to ensure the Liberal Coalition Government held the upper hand in negotiations with East Timor over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap. The East Timor government stated that it was unaware of the espionage operation undertaken by Australia.

Here is further proof that the Australian government bureaucrats, when they deem it appropriate, use electronic equipment to gain an upper hand, as was the case discussed above and the COT arbitrations. We COT Cases never stood a chance against these secret government officials with no qualms about whom they harm.

Tragically, Helen passed away in 2004. Years later, I reflected on her initial encouragement and sent a draft of the original version of my book, "Absent Justice," to her husband, Geoff Handbury. I recalled my conversation with Helen and sought his guidance on the best way to present a copy of my book to Rupert Murdoch.

On October 17, 2012, I received a response from Mr. Handbury—a beautifully handwritten letter that showcased exquisite, old-fashioned penmanship, a rarity in today’s digital age. By then, he was 87 years old and was deeply respected for his philanthropic contributions to numerous vital projects in Victoria. However, with time, he felt he could no longer help. Nevertheless, I treasure how Rupert Murdoch’s sister recognized my “intriguing story” as one worth sharing with her brother, and I am profoundly grateful for her kind and encouraging remarks.

Before we progress further, it's essential to highlight the impactful statements made by Helen Hndbury regarding the plight of crime victims. She powerfully noted that irrespective of the type of crime involved, the assurance that someone genuinely cares and is ready to offer support can significantly aid a victim in their journey to healing. One of Helen's most formidable obstacles was the assistance I provided to the Australian Federal Police (AFP), alongside their hesitance to help Mr. when I sought their intervention. This unwillingness from the AFP and their protection of Telstra allowed the telecommunications giant to continue undermining the COT Cases even after the AFP had drawn their conclusions. Despite having clear evidence in their files that demonstrated Telstra's misuse of electronic technology to sabotage the arbitration claims related to persistent telephone issues, the complications surrounding these cases persisted for years, exacerbating the struggles of those affected.

In February 1994, I was contacted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) with critical information: I was required to systematically differentiate the telephone complaints lodged by my single club patrons since 1990 from those submitted by educational institutions and other organizations during the 1990s, which had also expressed dissatisfaction with my services. This distinction was imperative, as the AFP had revealed that Telstra—Australia’s predominant telecommunications provider—had been methodically recording the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of my single club members over an extended period. These records, meticulously maintained within Telstra's internal files, became the focal point of an ongoing investigation.

Subsequent to this revelation, the AFP recommended that the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) consider the suspension of the COT arbitration proceedings. However, the TIO opted not to act on this suggestion. The AFP's recommendation was significant, underscoring the necessity for a comprehensive investigation into how Telstra, as a major entity in the telecommunications sector, acquired such nuanced details regarding my telephone communications. The investigation involved tracing caller identities and their geographical locations, which frequently originated from unexpected regions seemingly unrelated to my business operations. Warwick Smith, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, similarly declined to suspend the arbitrations.

Additionally, the inquiry aimed to ascertain how Telstra was able to determine the exact times at which my office staff departed the holiday camp during my absence while I was occupied with promotional activities for my business. This raises substantial concerns about the extent of Telstra's surveillance capabilities and data collection methodologies.

Exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) clearly show that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

Does Telstra expect the AFP to accept that every time this officer left the Portland telephone exchange, the alarm bell set up to broadcast my telephone conversations throughout the Portland telephone exchange was turned off every time this officer left the exchange? What was the point of setting up equipment connected to my telephone lines that only operated when this person was on duty? When I asked Telstra under the FOI Act during my arbitration to supply me all the detailed data obtained from this special equipment set up for this specially assigned Portland technician, that data was not made available during my 1994.95 arbitration and has still not been made available in 2025.

This individual is the former Telstra Portland technician who supplied an unknown person named 'Micky' with the phone and fax numbers that I used to contact them via my telephone service lines (Refer to Exhibit 518 FOI folio document K03273 - AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541)

Another particularly troubling FOI document involved Telstra documenting a telephone call made by the proprietor of an Adelaide pizza establishment from a location substantially removed from my typical contacts. This situation necessitates further examination into how Telstra accurately tracked communications. Moreover, it is concerning how Telstra identified a specific bus company in their notes related to my tender for transporting groups to my business, particularly since I had engaged with five other firms, none of which were referenced in their documentation. This crucial line of inquiry is also addressed in the transcripts, which emphasize the need for transparency and accountability Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1.

Under the directive of the AFP, I was assigned the formidable task of translating my detailed diary entries from my desktop booking exercise books into neatly organized hard-copy diaries. It was stipulated that these diaries remain strictly confidential and not be disclosed to Telstra under any circumstances. While I engaged in this meticulous task, the AFP concurrently investigated alarming reports of phone and fax hacking that impacted my operations.

Regrettably, a serious oversight occurred several months later: the hard-copy diaries, which my arbitration claim advisors assured would be safeguarded during the AFP's thirteen-month investigation, were inadvertently sent to Telstra by these advisors.

What happened next can be viewed by clicking on the Logbook image above.

Before the arbitration proceedings commenced, the information detailed in the report from Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) was initially prepared by BCI, a highly esteemed and technologically advanced telecommunications company in Canada. BCI asserted that they had executed a staggering 15,590 test calls to a particular telephone exchange; however, this exchange could not support the specialized equipment utilized by Bell Canada International Inc.

To simplify, Telstra managed to persuade BCI that successful testing of the Cape Bridgewater unmanned telephone switching exchange had occurred between November 4 and November 9, 1993, spanning a staggered five-day period. Nonetheless, this assertion was fundamentally flawed, as the Cape Bridgewater exchange lacked the necessary infrastructure to accommodate the CCS7 testing equipment that BCI claimed was employed. This advanced CCS7 monitoring technology, known for its sophistication, would not have been able to generate those test calls. The closest exchange equipped to handle the CCS7 specifications was located a significant 118 kilometres away from the unmanned Cape Bridgewater exchange, further highlighting the implausibility of the tests reported by BCI.

File 11 - BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46) is the sworn witness statements provided by Telstra's Christopher James Doody on December 12, 1994, making it clear on page two that the sole telephone exchange in my area capable of supporting the Common Channel Signaling System No. 7 (CCS7) was the Warrnambool AXE exchange. Similarly, File 12 -BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46) contains the witness statement prepared by Telstra's David John Stockdale, dated December 8, 1994. In this statement, Mr. Stockdale, under oath, explicitly confirms at point 20 that the CCS7 system could only function at the Warrnambool exchange. Despite this compelling evidence, Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator overseeing the case, unjustly allowed Telstra to cite the report from Bell Canada International Inc., leaving significant doubts about the integrity of the arbitration process.

This raises critical questions: What specific telephone exchange did Telstra utilize during these purported test calls? Why did the COT arbitrator fail to discard the Bell Canada International report from Telstra's arbitration defence despite its questionable validity?

It is crucial to emphasize that both Christopher James Doody's witness statement from Telstra, dated 12 December 1994, and David John Stockdale's statement from 8 December 1994, reference my ongoing telephone issues. These individuals provided their accounts under oath, yet their assertions do not correspond with the 2 to 212 specific points identified by the government communications authority AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, which were derived from Telstra's own records. The government has asserted that my business has suffered from severe deficiencies in telecommunications service over almost seven years, as outlined in my arbitration claim. In particular, point 209 highlights the extent of these issues noting:

Point 209 – “Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

I encourage the reader to reflect on the claims made by both Telstra and the arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, regarding the unresolved issues I faced with my phone during the arbitration proceedings. Their assertion starkly contradicts the extensive evidence compiled on absentjustice.com, which vividly details the persistent challenges I encountered. Had Telstra and Bell Canada International Inc. been compelled to re-evaluate their testing methodologies comprehensively, my ongoing phone and faxing problems would probably have been rectified during my arbitration in 1994.

As detailed on this homepage, the situation unfolded further when the Canadian government, upon uncovering these discrepancies, supported my efforts to urge Bell Canada International to come forward. This was essential for me to appeal my arbitration award, an action that occurred in July 1995. Since then, neither Bell Canada International Inc. nor Telstra has accepted accountability for their part in obstructing the course of justice. It is important to note that knowingly providing false information under oath in Australia is a serious crime. I invite you to read on for more insights into this matter.

A gripping and unsettling narrative emerges as Telstra acquires crucial evidence, revealing a shocking reality. It may astonish readers to learn that a government-owned corporation could stoop to such unethical practices against the COT Cases. Yet, disturbingly, not a single individual has faced accountability for these unlawful actions—much like the harrowing experience when I received my third threat during my arbitration process. This menacing communication was crafted by someone with privileged access to my arbitration submission, which I had diligently submitted to the arbitrator on June 15, 1994.

Within the intricate framework of the Arbitration Agreement I signed on April 21, 1994, several clauses were meticulously outlined, but one stood out as the most significant. This critical clause stipulated that the arbitrator could not disclose any information submitted by the claimant to the defendant (Telstra) until the claimant had conclusively proven their claim was final. In a surprising turn of events, however, the arbitrator chose to share that sensitive claim material with Telstra, allowing the corporation, from 15 June 1994 to 12 December 1994, a full six months to formulate a defence against the assertions made in my letter of claim. Attached herewith is my...Letter of Claim → CAV P3- Exhibit 8- Exhibit 9. Dr Hughes is currently a Senior Partner at Davies Collison Cave.

I seek to gain an understanding of the potential responses from the partners and associates at Davies Collison Cave, an esteemed international law firm headquartered in Melbourne, should Dr Gordon Hughes, the current Principal Partner, disclose that he authorized full access to my claim materials by Paul Rumble, the senior arbitration consultant for Telstra, for six months. This authorization is particularly concerning, as it contravenes the stipulations of the arbitration agreement, which explicitly limited access to one month.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that Paul Rumble is the same individual from whom the Senate is still awaiting a comprehensive explanation regarding threatening communications he directed towards me via telephone rather than the appropriate communication channels at a designated Melbourne gymnasium. The implications of these unauthorized actions and the associated threats raise significant concerns regarding the integrity of the arbitration process and the ethical standards upheld by the firm. Considering how the leadership at Davies Collison Cave may address these serious issues is imperative, as they could have far-reaching consequences for all parties involved.

Late one evening, I received a phone call from Paul Rumble, one of Telstra's two arbitration liaison employees. During the call, he threatened that Telstra would cease providing me with Freedom of Information (FOI) documents. The reason for this drastic measure, he claimed, was my decision to share the documents with the Australian Federal Police. I had done so to assist with their investigations into the unlawful interception of my telephone conversations and the tampering of arbitration-related faxes. Despite the gravity of these legal breaches, neither Warwick Smith nor Dr Gordon Hughes—the appointed arbitrator—was willing to investigate the matter further.

A brief overview of the power that Telstra had over the Establishment during the COT arbitrations follows:

Government Corruption

Threats made during my arbitration

On July 4, 1994, amidst the complexities of my arbitration proceedings, I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra's arbitration defence team representative. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred an entire month before the arbitrator was legally obligated to share such information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. I poured considerable effort into crafting this detailed letter, carefully choosing every word. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no plans to submit any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardize my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could impact the arbitrator's decisions regarding my case.

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on September 26, 1994. During this visit, they began to pose probing questions regarding my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result of this situation, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the Senate. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

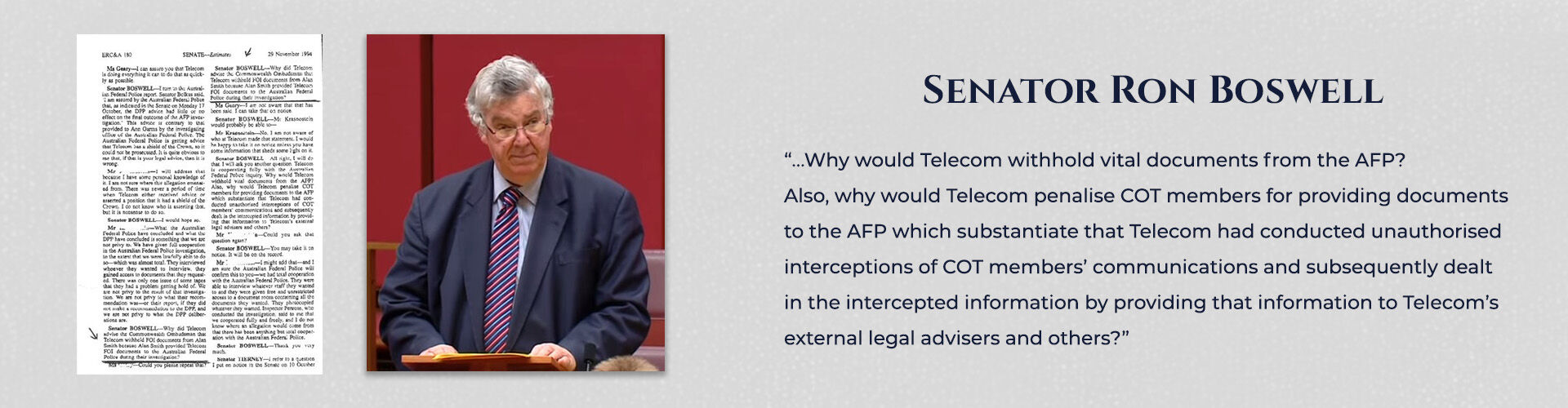

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this - no one in the TIO office or government has ever investigated the disastrous impact the withholding of documents had had on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen, who had assisted the AFP in their investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations, was so severely disadvantaged during a civil arbitration.

Pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts provide a comprehensive account establishing Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

Firstly, Mr. Rumble actively obstructed the provision of essential arbitration discovery documents, which the government was legally obligated to provide under the Freedom of Information Act. This obligation was contingent on my signing an agreement to participate in a government-endorsed arbitration process. By imposing this condition, Mr Rumble undermined a legally established protocol, effectively manipulating the process for his benefit and jeopardizing my legal rights.

Secondly, I uncovered that Mr. Rumble had a substantial influence over the arbitrator, resulting in the unauthorized early release of my arbitration interim claim materials. This premature revelation directly conflicted with the timeline stipulated in the arbitration agreement that both Telstra and I had formally signed. Specifically, Telstra gained access to my interim claim document five months earlier than what was permitted under the agreed-upon terms. This breach of protocol violated the integrity of the arbitration process and provided Telstra with an unfair advantage in their response to my claims.

Regrettably, members of Australia’s Establishment—among them Dr Gordon Hughes and Warwick Smith, both of whom have since been honoured with “Orders of Australia”—chose not to hold Telstra accountable for the pressing issues I and several COT Cases were forced to endure during our arbitrations.

I must alert the reader to the following:

The first of eight damning letters (which form part of my COT story) was from John Rundell, the Arbitration Project Manager, on 18 April 1995, advised the TIO, the arbitrator and the TIO counsel that: “Any technical report prepared in draft by Lanes will be signed off and appear on the letter of DMR Inc." (Prologue Evidence File No 22-A).

“It is unfortunate that there have been forces at work collectively beyond our reasonable control that have delayed us in undertaking our work.

“Any technical report prepared in draft by Lanes will be signed off and appear on the letter of DMR Inc.” (see Prologue Evidence File No 22-A)

When Dr. Gordon Hughes, Warwick Smith, and Peter Bartlett—three qualified lawyers—decided to conceal the pivotal letter dated April 18, 1995, from the four COT cases, they inadvertently played a crucial role in facilitating the “forces at work” that aimed to undermine the arbitrations of all four cases. Had John Rundell fulfilled his obligation to share a copy of his letter with the four COT cases, we—all claimants seeking justice—could have approached the Supreme Court to compel the arbitrator to explain why the COT cases had not been notified about these insidious forces. Such transparency might have prompted the Supreme Court to take action, demanding answers regarding why Telstra's threatening behaviour towards me had not been thoroughly investigated. At that time, Telstra was already under scrutiny for the serious allegations of intercepting our phone conversations and arbitration-related faxes without securing written consent from the COT claimants. This situation highlighted a troubling disregard for the integrity of the arbitration process and the rights of those involved.

Also, in this 18 April 1995 letter, John Rundell (FHCA) was so openly deceptive when stating, “Any technical report prepared in draft by Lanes will be signed off and appear on the letter of DMR Inc.” (See Prologue Evidence File No 22-A).

I firmly believe that John Rundell acted deceptively. On March 9, 1995, all four COT Cases received a written notification from Warwick Smith (the administrator to the arbitrations) stating that Paul Howell, from DMR Group Inc. based in Canada, would be the primary consultant responsible for preparing the final technical evaluation reports. This decision was made consciously, as we had serious reservations about Lanes, mainly due to their connections with former Telstra officials, which raised concerns about their impartiality.

Our doubts about Lanes were well-founded. While they were tasked with investigating our arbitration complaints regarding the Ericsson-installed telephone equipment in Telstra exchanges—essential systems that directly impacted our businesses—Lanes was simultaneously being acquired by Ericsson for an undisclosed amount. This acquisition created a troubling conflict of interest; it meant that all technical documents associated with the investigations into the COT Cases, which Lanes was working on during our arbitration, would ultimately be transferred to Ericsson. Such circumstances allowed for significant concerns regarding the integrity and transparency of the entire investigation (Refer to Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden).

I urge you to examine the statements delivered by six Senators in the Senate on March 9, 1999, as they shed light on the gravity of our situation, and I quote them directly:

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Regrettably, because my case had been settled three years earlier, I and several other COT Cases could not take advantage of this investigation's valuable insights or recommendations. Pursuing an appeal of my arbitration decision would have incurred significant financial costs that I could not afford as shown in an injustice for the remaining 16 Australian citizens.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On 29 June 1995, the Canadian government appeared concerned that Telstra's lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now known as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne), provided false Bell Canada International Inc. tests. These tests were meant for Mr Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, to review before he travelled to Portland to assess my mental health during the arbitration.

The issue came to light on 23 May 1995, when a late Freedom of Information (FOI) release by Telstra’s Ted Benjamin revealed that Telstra had concealed this evidence since I requested it in May 1994, only to release it nearly a year later. Even the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, who had previously supported Telstra's arbitration defence throughout my case, expressed concern. My appeal lawyers at Taits Solicitors in Warrnambool were also troubled by this development. They wrote to AUSTEL (the then-government communication authority (now operating under the banner of ACMA) seeking information regarding the Bell Canada International (BCI) and NEAT testing processes conducted at the Cape Bridgewater RCM in November 1993 - (AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233 - See 185).

In response to their inquiry on 12 July 1995, Cliff Mathieson from AUSTEL wrote,

"The tests you refer to were neither arranged nor carried out by AUSTEL. Questions relating to the conduct of the test should be directed to those who conducted or claimed to have conducted them."

A storage letter to have been sent after Cliff Mathieson had already written eighteen months previous on 9 December 1993, before Telstra used the BCI report as Defence Material, advising Telstra to provide the “assessor(s)” of the COT processes with a copy of his letter regarding the BCI tests, which he declared did not go far enough. This letter was NOT provided to Dr Hughes (the arbitrator) or the COT Cases, as AUSTEL had directed, which makes Telstra’s use of the BCI Report even more unconscionable.

It is essential to highlight that critical information was not communicated to the Canadian Government or Tait Lawyers—who may have taken a different approach based on this knowledge—regarding the actions of Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now operating as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne. This firm submitted misleading BCI tests, falsely claiming that 15,590 successful test calls had been directed to my local exchange, which services my business. These tests occurred at an entirely different telephone exchange, resulting in a substantial misrepresentation of the facts.

Upon being informed of this deception, Ian Joblin expressed his significant concerns. When I made it clear to him that he had been misled, he acknowledged the seriousness of the situation. He indicated that he would advise Telstra to examine the evidence I had provided thoroughly. His acknowledgement of the validity of certain aspects of my claims underscored the weight of the matter, and he assured me that this would be prominently included in his forthcoming report.

However, a troubling oversight became evident when this report was submitted to the arbitration process. The 'witness statement' intended to validate Mr Joblin's findings was signed solely by Wayne Maurice Condon of Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne).

The consultation I conducted with Ian Joblin on the day of his visit to Portland to evaluate my mental health occurred in the saloon bar of the Richmond Henty Hotel. This environment, characterized by the ambient noise of hotel patrons and the movement of guests, was not conducive to a private consultation, as it significantly differed from the standard settings of a designated consultation room at the Portland Hospital or a physician's office. I communicated my concerns regarding this arrangement to the arbitrator, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, and in a formal letter addressed to Telstra's Chief Executive Officer, Frank Blount. Transferring small cards from point A to points B and C in full view of other hotel guests was particularly discomforting. Unfortunately, I did not receive an official apology from any party involved in the arbitration process.

However, with that said, it is essential to note that I revealed to Mr. Joblin the troubling information that Telstra had been monitoring my daily activities since 1992. Furthermore, I presented Freedom of Information (FOI) documents indicating that Telstra had redacted critical portions of the recorded conversations regarding my case. This disclosure visibly troubled Mr. Joblin, who realized that he had been misled by the legal representatives of Telstra, specifically those from Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne. I was able to provide compelling evidence that this law firm had supplied Mr. Joblin with a misleading report concerning my telecommunications issues prior to our interview. Mr. Joblin acknowledged that his findings would address these troubling concerns in light of this information. However, it is crucial to point out that despite the situation's gravity, no adverse findings were made against either Telstra or Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne.

Mr. Joblin insisted that he would note in his report to Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne, the inappropriate nature of Telstra's treatment of me. He emphasized that their methods of assistance warranted careful review. Nevertheless, it is essential to highlight that no adverse findings were documented against Telstra or Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne.

A critical question remains: Did Maurice Wayne Condon intentionally remove or alter any references in Ian Joblin's initial assessment regarding my mental soundness? On March 21, 1997—twenty-two months following the conclusion of my arbitration—John Pinnock, the second appointed administrator for my case, formally reached out to Ted Benjamin at Telstra (refer to File 596 - Exhibits 589 to 647). He raised two crucial inquiries:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin (clinical psychologist).

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes (the arbitrator) compared to the signed statement?"

The fact that Maurice Wayne Condon, acting as Telstra's legal representative from Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne, signed the witness statement without securing the psychologist's signature raises serious questions about the level of influence and power that Telstra's legal team wields over the arbitration process in Australia. Even more concerning is that I have not received any response from either the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman office, Telstra or Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne regarding the questions raised on 21 March 1997 by the administrator of my arbitration, John Pinnock, written during the six years of the statute of limitations which would have allowed me to use any adverse response received by John Pinncock. It is now 2025, and it is blatantly apparent the big end of town has won again.

On 23 October 1995, Portland solicitors Bassett & Sharkey formally contacted John Pinnock, the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman. In their correspondence, they expressed serious concerns that Telstra was relying on BCI test results, which were known to be impractical, as part of their defence in an arbitration case. They emphasized the need for further clarification on this alarming issue (File 198 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233).

Just a few days later, on 26 October 1995, Minter Ellison, acting on behalf of the TIO, drafted a response to Bassett & Sharkey. Within this response was a statement asserting, “Although the Arbitrator had a copy of the Bell Canada Report, it does not appear to have ever formally been put into evidence.” This assertion was misleading and factually incorrect, as Minter Ellison and the TIO’s office knew that Telstra’s arbitrator had cited the BCI report as significant evidence presented during the arbitration (File 199 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233).

Moreover, both parties were cognizant that on 23 October, Telstra’s Freedom of Information officer had released compelling proof previously requested by me in May 1994 (a full twelve months earlier). This documentation conclusively demonstrated that BCI had not conducted their tests at Cape Bridgewater at the time and location specified in the Bell Canada International Inc. report, raising serious questions about the integrity of the evidence used in the arbitration process.

It is essential to visit the 8 and 10 August 2006 witness statements.