Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers. Instances of foreign bribery, foreign corrupt practices, kleptocracy, and foreign corruption programs, absentjustice.com—the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption—stand shoulder to shoulder with any true crime ... and international fraud against the government present significant challenges. Visitors to this website have drawn parallels between its content and a comprehensive portrayal of criminal activities encompassing fraud.

Delve into the pervasive corruption that has infiltrated the government bureaucracy and stained the integrity of the Court of Arbitrations. This deep-seated issue reveals the individuals behind these egregious acts, highlighting how their actions have undermined the rule of law. As you explore this troubling landscape, you will discover how unscrupulous lawyers and compromised arbitrators have collaborated to obscure the truth, contributing to a cycle of deception and injustice that affects countless lives and undermines public trust in the legal system.

My name is Alan Smith, and this is the story of my enduring battle against a telecommunications giant and the Australian Government. This struggle has twisted and turned, weaving through the corridors of power since 1992. I have faced elected officials, government departments, regulatory bodies, the judiciary, and Telstra, formerly Telecom. My quest for justice continues unabated to this day.

The roots of my story trace back to 1987, when I made the pivotal decision to leave behind my life at sea, a life I had embraced for the previous 20 years. Craving a new land-based occupation to usher me into retirement, I yearned for a venture that would provide stability and fulfilment.

Hovering your cursor or mouse over the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp image below will lead you to a March 1994 document referenced as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings. This document confirms that government public servants investigating my ongoing telephone issues supported my claims against Telstra, particularly between Points 2 and 212. Evidently, if the arbitrator had been presented with AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, he would have awarded me a significantly higher amount for my financial losses than he ultimately did.

As a devoted hospitality professional, I had always dreamt of running a school holiday camp. Imagine my excitement when I stumbled upon the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre, a hidden gem advertised for sale in *The Age newspaper*. Nestled in the picturesque rural landscape of Victoria, near the quaint maritime port of Portland, it seemed to promise everything I had ever wanted. After conducting what I believed to be thorough due diligence to ensure the business was sound, I never thought to check one critical factor: whether the phone service worked.

Within a week of taking over, it became clear that I had stepped into a quagmire. Customers and suppliers began contacting me, only to express frustration at their failed attempts to connect over the phone. I grappled with the harsh reality of running a business plagued by an unreliable phone service—at best, glitchy, at worst, completely non-existent. Therefore, my dreams began to slip away, strained by unforeseen losses.

Thus began my saga—a relentless quest to secure a functioning phone line for my business. Along this tumultuous journey, I received overdue compensation for my business losses and many broken promises that my issues would be resolved. Yet, here I am, all these years later, still grappling with the same unresolved problems. I sold the business in 2002, but later owners faced similar misfortunes, trapped in a cycle of despair.

Fortunately, I found companionship in other independent businesspeople devastated by poor telecommunications services. We became known as the Casualties of Telecom, or the COT cases. All we have ever wanted is for Telecom/Telstra to officially recognise our struggles, rectify the myriad issues, and compensate us for our losses. Surely that is not too much to ask for a reliable phone service?

At the outset, we called for a full Senate investigation into the telecom giant and the specific grievances we faced. Yet, instead of accountability, we were offered an arbitration process as an alternative solution. It seemed like a fair opportunity to resolve our issues, so we accepted. Back then, we held onto hope that the technical malfunctions hindering our phones would finally be addressed.

Alas, that hope was dashed almost immediately as suspicions arose about the integrity of the arbitration process. We were promised access to essential Telecom documents for constructing our case, yet these documents were never made available. Adding to our frustrations, we later learned that our fax lines were being illegally tapped during the arbitration process. With the full weight of the Government against us, we found ourselves defeated.

To compound our challenges, we were deceived into signing a confidentiality clause that has since stymied all our efforts to speak out. While I may be risking penalties by divulging this information, I feel I have no other choice.

The next chapter of our struggle involved exhausting every avenue to obtain the promised but withheld documents through Freedom of Information (FOI). We are convinced that substantial evidence exists to support our assertion that the lines were malfunctioning and had not undergone proper testing according to established protocols. However, for that evidence to be useful, we must first receive those documents.

What do you think? Are we imagining this, or have we truly stumbled upon a web of massive corruption and collusion among public servants, politicians, regulatory bodies, and Telstra, all designed to shield Telstra at the expense of Australian rural businesses?

After surviving a harrowing heart attack followed by a double bypass surgery, I found myself in a consultation with my doctor, who, recognizing the gravity of my situation and familiar with my experiences as a COT claimant, expressed his sympathy. Yet, amid our conversation, he posed a question that lingered ominously in the air: "Why am I not surprised?"

As I pen these thoughts in 2025, the weight of revisiting our story's intricate and tumultuous details on absentjustice.com fills me with unsettling anxiety. Each time I delve into the narratives we’ve crafted—a mosaic of anguish and resilience—I grapple with an overwhelming inability to articulate a fitting conclusion to this dreadful saga. It is disheartening that, despite my fervent efforts, I remain at a loss for the words to encapsulate the disaster that has ensnared us for years.

At the core of our struggle lies the grim reality that none of the COT cases should have placed honest Australian citizens in a position where we faced unaddressed crimes that inflicted deep harm. These offences were perpetrated against us while we were engaged in a governmental-sanctioned legal arbitration process that promised justice. The complexities of our situation can be divided into two primary issues: on one side are those individuals who colluded with Telstra to execute these unaddressed wrongs, and on the other, Telstra itself—an institution wielding immense power, capable of thwarting any investigations by authorities, including governmental bodies. This disturbing dynamic is thoroughly discussed on this website.

It is imperative to stress that every detail chronicled on this website is meticulously correct and adamantly supported by irrefutable evidence, readily available for public examination. Recently, during heartfelt discussions with fellow members of the COT group—despite two individuals facing serious health challenges—we reached a consensus. Given our immense stress, we believed it would be more prudent to present our stories to the public as they currently stand on the website, even if it diverges from the polished presentation we had initially envisioned.

Judicial impartiality is a cornerstone of true justice. Judges and arbitrators must be able to resolve legal disputes without personal bias or prejudice. A conflict of interest can severely undermine this impartiality, making disqualification necessary. However, during the COT arbitrations, our arbitrator, who presided over the first four cases, had previously served as a legal and business advisor to one of those claimants, a crucial fact that was withheld from the other three.

Clicking on the following FOI image shows that during the second interview conducted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) at my business on 26 September 1994, they asked me 93 questions as part of their investigation into the bugging issues, refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1. As my arbitration process progressed, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) became aware that the defendants had threatened to stop providing me with any more discovery documents if I continued to help the AFP with their investigations into my complaints that those very same defendants were intercepting my phones and faxes and, of course, those documents were vital: I couldn’t support my arbitration claim without them. Most of these received documents were either blanked out or were undecipherable.

What options remained for us in this seemingly endless struggle? We had lost the arbitration process, primarily due to our inability to access the crucial FOI and the requested discovery documents. Subsequently, we also lost the chance to appeal because we had no access to the same material, which would have allowed us to determine our chances of winning such an appeal. Should we surrender to defeat or muster the strength to continue the fight?

After facing a life-altering heart attack, which felt like a thunderclap echoing through my chest, and enduring the gruelling experience of double bypass surgery, I found myself seated in a doctor's office, my pulse still racing from the surreal events. My doctor, acutely aware of the gravity of my situation and familiar with my challenging experiences as a COT claimant, leaned in with a sympathetic expression that conveyed both concern and understanding. However, amid our conversation, he posed a disquieting question that hung heavily in the air: "Why am I not surprised?"

Now, as I pen these thoughts in the year 2025, the weight of revisiting the intricate and tumultuous saga of our journey on absentjustice.com brings an unsettling wave of anxiety. Each time I dive into the narratives we’ve woven—a vivid tapestry of anguish, perseverance, and resilience—I struggle with an overwhelming inability to find the right words to encapsulate this distressing chapter of our lives. It is profoundly disheartening to realise that, despite my fervent attempts, I remain at a loss for adequate language to summarise the disaster that has ensnared us for so long.

At the core of our struggle lies the harsh reality that no honest Australian citizen should ever have been thrust into a position where we were left to confront unaddressed crimes that inflicted deep scars on our lives. These offences were committed against us while we engaged in a painstakingly protracted governmental-sanctioned legal arbitration process, which held the promise of justice and resolution. The complexities of our ordeal can be distilled into two main issues: first, the shadowy figures who colluded with Telstra to perpetrate these unresolved injustices; and second, Telstra itself—an enormous institution wielding formidable power, capable of obstructing any investigations by authorities, including governmental bodies. This disturbing dynamic is thoroughly examined and documented on our website.

It is vital to stress that every detail outlined on this platform is meticulously accurate and robustly supported by indisputable evidence, readily accessible for public scrutiny. Recently, during heartfelt discussions with fellow members of the COT group—some of whom were grappling with significant health challenges—we reached a collective decision. Given the overwhelming stress plaguing us, we agreed it would be wiser to present our stories in their current unrefined state on the website, rather than waiting for the polished narratives we initially envisioned.

Judicial impartiality stands as a cornerstone in the search for true justice. For judges and arbitrators, the capacity to resolve legal disputes without personal bias or prejudice is essential. A conflict of interest can severely undermine this impartiality, making disqualification unavoidable. However, during the COT arbitrations, our arbitrator—having previously served as a legal and business advisor to one of the claimants—failed to disclose a crucial fact that could have altered the course of the proceedings.

On May 12, 1995, this same arbitrator warned the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) that the arbitration agreement employed in my case—the inaugural arbitration among the four—was "not a credible document." Yet, despite this alarming revelation, he proceeded without hesitation. In the aftermath, the arbitration rules were modified for the remaining three claimants, affording them over thirteen additional months to prepare their cases—a glaring indicator of inequity that left me feeling marginalised.

Moreover, the arbitrator granted that same previous client an extended period to secure Freedom of Information (FOI) documents from Telstra and respond to the defence of his case, permitting him an astonishing thirty months longer than I was given. This stark disparity illustrates a blatant bias that cannot be ignored. When the government became aware that this arbitrator had previously assisted that specific claimant during a Federal Court action in 1990—addressing the very issues now under consideration—one would expect immediate disqualification. Yet, as our narrative unfolds, we discover that the arbitrator remained unchallenged and firmly in place, casting a dark shadow over the quest for justice.

The process extended from 1994 until 2011. In May that year, my final request for the withheld Freedom of Information (FOI) documents was presented to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) in Melbourne. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) was designated as the respondent. The Australian Government Solicitors were appointed to represent the ACMA, bringing their legal expertise to the proceedings. Unfortunately, despite my efforts, I lost the appeal.

Despite receiving official advice from AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) that we would be unable to prove our ongoing phone problems without the promised documents—the very same documents AUSTEL had previously relied upon to make its findings against Telstra—I found myself in a frustrating situation. In 2008 and 2011, AUSTEL/ACMA stubbornly refused to provide me with those essential documents, which I had desperately needed since 1994 to substantiate my arbitration claims. The term "crawl" hardly captures the extent of my frustrations; "unconscionable" and "evil" aptly reflect the callousness and indifference displayed by these government bureaucrats at AUSTEL/ACMA. Their actions felt both obstructive and profoundly unjust, adding to the despair surrounding our unresolved issues.

In the lead-up to my submission for the AAT hearing in October 2008, I unexpectedly interacted with one of the tribunal’s administrators. This individual approached me and shared that they had read many of my letters submitted to the AAT since my initial request in February 2008. They said they recognised my dedication and the clarity I articulated my submissions, noting that my conduct was not frivolous. Although some viewed my claims as vexatious, their encouragement left me hopeful for a positive outcome in the hearing.

Transcripts from the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) dated 8 October 2008 (No V2008/1836) reveal significant testimony provided by Graham Schorer, the spokesperson for COT cases. In an official capacity under oath, Mr. Schorer conveyed to two government attorneys and a senior member of the AAT panel that he and I were actively seeking access to a series of freedom of information documents that Telstra had withheld during the critical arbitration discovery process. Our primary objective was to compile a comprehensive and factual narrative that would illuminate and potentially open doors for other similar cases, fewer than sixteen, that could prompt the Senate to advocate for a thorough government investigation into the validity of our claims.

What Mr. Schorer failed to disclose to the attorneys or the presiding judge, Mr. GD Friedman, was a crucial detail that had bearing on our case: unbeknownst to me, the government had concealed AUSTEL Adverse Findings from both itself and the arbitrator in March 1994. Alarmingly, these findings were provided to Telstra a mere six weeks before I signed my arbitration agreement. This transfer of information was strategically timed to assist Telstra in mounting a defence against my claims regarding the persistent problems I was experiencing with telephone and fax services, continuing even on the day the information was bestowed upon them.

The government appeared to operate under the belief that preventing me from substantiating my claims was imperative. It was not until November 2007—twelve years after the government initially supplied these AUSTEL Adverse Findings to Telstra—that I received access to this critical document. By this point, the utility of the findings had diminished significantly, as they were now five years past the six-year statute of limitations for filing an appeal against my award.

A thorough examination of this report may lead an impartial observer to conclude that the government has patently breached its obligations towards me as an Australian citizen. This breach appears to stem from a discriminatory practice favouring Telstra, a corporation wholly owned by the Australian government, representing the collective interests of the Australian people, during that significant period in March 1994.

On 3 October 2008, senior AAT member Mr G D Friedman considered these AAT hearings and, on 3 October 2008, stated to me in open court in full view of two government ACMA lawyers.

“Let me just say, I don’t consider you, personally, to be frivolous or vexatious – far from it.

“I suppose all that remains for me to say, Mr Smith, is that you obviously are very tenacious and persistent in pursuing the – not this matter before me, but the whole – the whole question of what you see as a grave injustice, and I can only applaud people who have persistence and the determination to see things through when they believe it’s important enough.”

During the above ten-month AAT hearing, I provided the AAT with a 158-page report and 1,760 plus exhibits, along with 23 letters and attachments to the ACMA board, proving beyond all doubt that Telstra had violated my human rights and that their leading arbitration engineer, Peter Gamble, had submitted known false documents to the arbitrator concerning his alleged successful service verification testing of my business telephone service lines.

How can the arbitrator, who had no control over the arbitration proceedings, continue concealing the reasons for refusing access to the telephone exchange logbooks that would prove or disprove each COT Case assertion in their arbitration submissions? These logbooks were essential records during the COT arbitrations because they meticulously document every daily fault reported by businesses and residences relying on Telstra telephone exchanges across multiple locations under scrutiny in Australia.

On 26 September 1997, after most of the arbitrations had been concluded, including mine, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, John Pinnock, who took over from Warwick Smith, formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

No amendment is attached to any agreement, signed by the COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those particular arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure – and neither was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide or deny the COT Cases the reason our requested telephone log books from the relevant telephone exchanges that serviced our businesses were withheld from us?

This information was crucial for evaluating the scope of the issues under investigation during the arbitration process and, therefore, understanding the impact on each affected party. The lack of transparency regarding this denial raises serious concerns about the integrity of the arbitration and the ability to effectively assess the reliability of the telecommunications services in question.

Hovering your cursor or mouse over the goverment locked caged document image below will lead you to a March 1994 document referenced as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings. This document confirms that government public servants investigating my ongoing telephone issues supported my claims against Telstra, particularly between Points 2 and 212. If the arbitrator had been presented with AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, he would have awarded me a significantly higher amount for my financial losses than he ultimately did.

Government records, meticulously detailed in Absentjustice-Introduction File 495 to 551, reveal a deeply troubling narrative that exposes significant flaws in the arbitration process. Alarmingly, AUSTEL disclosed its unfavourable findings to Telstra—the defendants—a month before I signed the arbitration agreement with them. This premature sharing of sensitive information not only raises concerns about the transparency of the process but also casts doubt on its overall fairness.

How has Freehills Hollingdale & Page (now operating as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne), Australia's largest and most prominent legal firm, evaded scrutiny by the Senate for their troubling actions during the COT arbitrations? Official government records indicate that their involvement with the COT cases should have ceased after October 1993 → (point 40 Prologue Evidence File No/2). Yet, despite this stipulation, Freehills Hollingdale & Page was still appointed as the defense attorneys for Telstra in the majority of the COT cases, including my own. It raises alarming concerns—how could they be permitted to validate witness statements never signed by the actual witnesses?

In a troubling turn, Telstra and its legal representatives, Freehills Hollingdale & Page, presented a fabricated Bell Canada International (BCI) report to Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, to read before Mr Joblin assessed my mental state. This misleading BCI document claimed that 15,590 test calls were successfully transmitted over four to five hours spanning five days, from November 4 to November 9, 1993, to my local telephone exchange at Cape Bridgewater. During my arbitration, this spurious information concerning my telephone claims was presented to Ian Joblin, who was part of Telstra's arbitration defence unit.

By utilising these deceptive BCI tests, Freehills Hollingdale & Page, aimed to create the impression that Ian Joblin would conclude I must be suffering from paranoia regarding my alleged phone issues. They implied that anyone of sound mind would not assert they were experiencing phone problems when, according to the fabricated BCI report, the 15,590 test calls were supposedly transmitted without incident. This manipulation of information raises serious concerns about the integrity of their defence and the implications for my claims.

Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) employed the highly regarded CCS7 monitoring equipment to generate an astonishing number of calls. However, the nearest telephone exchange equipped to handle this advanced CCS7 technology was 112 kilometres from my business location. This raises the question: where did the staggering 15,590 test calls ultimately end up? As you delve into this story, you'll uncover a troubling detail — Telstra audaciously contaminated the collected TF200 telephone by pouring wet and sticky beer residue into it after those phones departed from the COT Cases businesses. Adding to this bizarre scenario, Telstra sought to label other COT Cases members as mentally unstable, as evidenced by my narrative. This corporation has remained unchanged; the current Corporate Secretary, Sue Laver, holds the key to revealing the truth about the BCI (false test results) provided to Ian Joblin. All she needs to do to clarify matters is publicly dismiss my claims as frivolous in a media release, along with the evidence that my claims are false.

As detailed throughout this website, absentjustice.com, Telstra controls Australia's arbitration and mediation process. Readers can freely download the evidence in my mini-stories while navigating the website, which leaves no doubt that my claims are valid.

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehill Hollingdale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne signed the witness statement without the psychologist's signature being where it legally should be on the document as the law states it should be shows how much power Telstra lawyers have over the legal system of arbitration in Australia.

On 21 March 1997, twenty-two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to my arbitration), wrote to Telstra's Ted Benjamin (refer to File 596 Exhibits AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) asking:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin .

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?"

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehill's, signed the witness statement without the psychologist's signature is unlawful enough; however, with that said, the fact John Pinnock, administrator to my arbitration as well as the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman has in 2025, still not provided Telstra's official response concerning this dreadful conduct by Mautice Wayne Condon of Freehills Hollingdale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne shows how much power Telstra lawyers have over the legal system of arbitration in Australia.

Senate Hansard on 24 June 1997 (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia shows Senator Kim Carr asking Ted Benjamin, Telstra’s leading arbitration defence Counsel (Re: Alan Smith):

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

The most alarming issue surrounding Telstra’s intelligence networks established across Australia is the critical question of who within the Telstra Corporation possesses the expertise and government clearance to filter the extensive raw information gathered appropriately. This information must be cataloged impartially for future use, yet the process and oversight remain unclear.

PLEASE NOTE:

At the time of my altercation referred to in the above 24 June 1997 Senate - Parliament of Australia, my bankers had already lost patience and sent the Sheriff to ensure I stayed on my knees. I threw no punches during this altercation with the Sheriff, who was about to remove catering equipment from my property, which I needed to keep trading. I placed a wrestling hold, ‘Full Nelson’, on this man and walked him out of my office. All charges were dropped by the Magistrates Court on appeal when it became evident that this story had two sides.

Although Bell Canada did not respond to inquiries about the inaccuracies in their Cape Bridgewater BCI tests, the Canadian Government did respond, as illustrated in the following letter.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

The Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On 29 June 1995, the Canadian government appeared concerned that Telstra's lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now known as Herbert Smith Freehills, Melbourne), provided false Bell Canada International Inc. tests. These tests were meant for Mr Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, to review before he travelled to Portland to assess my mental health during the arbitration.

The issue came to light on 23 May 1995, when a late Freedom of Information (FOI) release by Telstra’s Ted Benjamin revealed that Telstra had concealed this evidence since I requested it in May 1994, only to release it nearly a year later. Even the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, who had previously supported Telstra's arbitration defence throughout my case, expressed concern. My appeal lawyers at Taits Solicitors in Warrnambool were also troubled by this development. They wrote to AUSTEL (the then-government communication authority, now operating under the banner of ACMA), seeking information regarding the Bell Canada International (BCI) and NEAT testing processes conducted at the Cape Bridgewater RCM in November 1993 (AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233 - See 185).

PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING TWELVE CHAPTERS.

Chapter 1

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens

Chapter 2

Betrayal deceit disinformation duplicity falsehood fraud hypocrisy lying mendacity treachery and trickery. This sums up the COT government endorsed arbitrations.

Chapter 3

Ending bribery corruption means holding the powerful to account and closing down the systems that allows bribery, illicit financial flows, money laundering, and the enablers of corruption to thrive.

Chapter 4

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens. Government corruption within the public service affected most if not all of the COT arbitrations.

Chapter 5

Corruption is contagious and does not respect sectoral boundaries. Corruption involves duplicity and reduces levels of morality and trust.

Chapter 6

Anti-corruption policies need to be used in anti-corruption reforms and strategy. Corruption metrics and corruption risk assessment is good governance

Chapter 7

Bribery and Corruption happens in the shadows, often with the help of professional enablers such as bankers, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents, opaque financial systems and anonymous shell companies that allow corruption schemes to flourish and the corrupt to launder their wealth.

Chapter 8

Corrupt practices in government and the results of those corrupt practices become problematic enough – but when that corruption becomes systemic in more than one operation, it becomes cancer that endangers the welfare of the world's democracy.

Chapter 9

Corruption in government, including non-government self-regulators, undermines the credibility of that government. It erodes the trust of its citizens who are left without guidance are the feel of purpose. Bribery and Corruption is cancer that destroys economic growth and prosperity.

Chapter 10

The horrendous, unaddressed crimes perpetrated against the COT Cases during government-endorsed arbitrations administered by the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman have never been investigated.

Chapter 11

This type of skulduggery is treachery, a Judas kiss with dirty dealing and betrayal. This is dirty pool and crookedness and dishonest. This conduct fester’s corruption. It is as bad, if not worse than double-dealing and cheating those who trust you.&a

Chapter 12

Absentjustice.com - the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption, it stands shoulder to shoulder with any true crime story.The following narrative about China and North Vietnam is a short story derived from the following twelve named chapters below. Gradually my aim is to transform these twelve chapters into mini-stories. This transformation includes various chronologies of events, which can be found on this website, along with supporting exhibits (the Evidence Files) that can be downloaded for free as readers engage with the story. Each exhibit can be accessed by clicking on it, providing visual support for the relevant parts of the narrative.At the age of 81, I felt compelled to share the events that I and several British seamen witnessed in the People's Republic of China in August 1967. My story, "Three Titled Flashbacks—China Vietnam," details these events.

I selected the image titled "TELECOM SPYING ON ITS EMPLOYEES" because it exposes the unsettling reality that Telecom (now rebranded as Telstra) was surveilling its employees and intruding into its customers' private lives. This invasive behaviour came to light in the case involving the Casualties of Telstra, where the company was embroiled in arbitration after it was revealed that customers' voices had been monitored for extended periods.

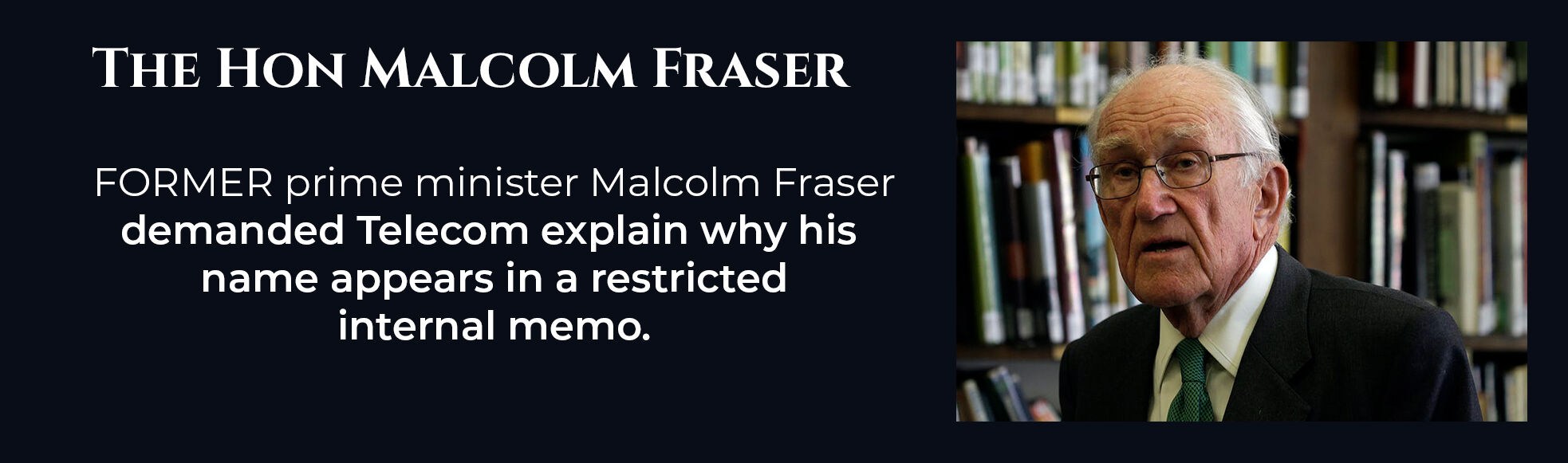

In my own experience, a series of documents were unintentionally released, though I find it difficult to believe this was an accidental oversight, because an insider at Telstra recorded nearly an entire A4 page of my conversations with former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser that had been redacted.

During two significant phone calls with Mr. Fraser, we delved into his time as Minister for the Army during the tumultuous Vietnam War era. I shared with him my troubling recollections of being interrogated in Communist China on espionage charges back in 1967. I also inquired if he remembered receiving a letter from me dated September 18, 1967, in which I recounted my harrowing experiences in Communist China and the alarming events witnessed by several seamen, including myself.

We witnessed Australian wheat being unloaded from our Hopepeak ship and then redirected to North Vietnam. In this country, Australian, New Zealand, and U.S. troops were actively engaged in a brutal war. This troubling situation prompted the crew, including me, to refuse to transport another load of grain from Australia back to Communist China, as we were deeply concerned about the implications of our actions.

For more information on this topic, please refer to Chapter 7- Vietnam Viet Cong.

British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman.

The Canadian government and its moral code of ethics.

The Canadian government strongly supported my claims against the fundamentally flawed report by Bell Canada International Inc., which Telstra used to defend itself in my arbitration claims. Additionally, a Canadian technical consultant from DMR Group Canada Inc., who was brought in as the principal technical consultant from Montreal, Quebec (H3B 4G7), confirmed that the arbitration process I was involved in would not have been allowed to proceed so unethically in North America.

By hovering your mouse over the Canadian flag image below, you can also learn about the strong ethical principles upheld by Canadian seamen. Despite facing significant challenges, they believed that sending wheat to Communist China—especially when that wheat was being redeployed to North Vietnam, a country at war with Australia, New Zealand, and the USA, where hundreds of troops were being killed or mained—was immoral and unethical, and therefore should not have continued.

Yet the Australian Government made a conscious decision to maintain its trade relations with Communist China, despite knowing that a significant portion of Australia’s wheat was being diverted to North Vietnam. This wheat was not merely a trade commodity; it had the potential to sustain North Vietnamese soldiers who were directly engaged in combat against Australia and its allies during the conflict. The ramifications of this trade raised serious ethical questions about the implications of supporting a nation that was opposing Australian, New Zealand and USA forces.

A striking similarity in my narrative regarding the Chinese Cultural Revolution is Canadians' perspective on democracy and the concepts of right and wrong. This is evident in Tianxiao Zhu's Footnote 169 → FOOD AND TRADE IN LATE MAOIST CHINA, 1960-1978, effectively highlighting the ethical standards Canadian seamen uphold. Unbeknownst to them, they supported several British seamen and one Australian seaman (myself), as I clearly illustrate in the narrative below.

Tianxiao Zhu's Footnote 83, 84 and 169, "83 In September 1967, a group of British merchant seamen quit their ship, the Hope Peak, in Sydney and flew back to London. They told the press in London that they quit the job because of the humiliating experiences to which they were subjected while in Chinese ports. They also claimed that grain shipped from Australia to China was being sent straight on to North Vietnam. One of them said,“I have watched grain going off our ship on conveyor belts and straight into bags stamped North Vietnam. Our ship was being used to take grain from Australia to feed the North Vietnamese. It’s disgusting.” (my emphasis)

"84... The Minister of Trade and Industry received an inquiry about the truth of the story in Parliament, to which the Minister pointed out that when they left Australia, the seamen only told the Australian press that they suffered such intolerable maltreatment in various Chinese ports that they were fearful about going back. But after they arrived in London, Vietnam was added to their story. Thus the Minister claimed that he did not know the facts and did not want to challenge this story, but it seemed to him that their claims about Vietnam seemed to be an “afterthought.”

"...169 In Vancouver, nine sailors refused to work on a grain ship headed to China: two of them eventually returned to work, and the other were arrested. Just when the ship was about to sail, seven more left the ship but three of them later returned to work. In Sydney, six Canadian sailors left their ship; they resigned and asked to be paid, but the Australian immigration office repatriated them. At that time a grain ship usually had crew members about 40 people. A British ship lost the Chief Officer and sixteen seamen, who told journalists that if the ship were going to the communist countries, they would rather go to jail than work on the ship."

Examining this wheat agreement made with the People's Republic of China during the Menzies government in the mid-1960s is essential. This controversial deal had significant implications, which were obscured by a government campaign to discredit British and Canadian merchant seamen, including myself. These brave individuals tried every conceivable legal way to expose this illicit diversion of wheat to North Vietnam.

Instead of receiving praise and support for their stance, they were slandered by the Liberal Coalition government of the time. This same government, twenty-seven years later, allowed five Australian citizens—out of twenty-one who had faced similar challenges with Telstra—to have their arbitration claims assessed by the Senate under a litmus test scenario. If the Senate ruled in favour of the litmus test case, the remaining sixteen claimants would be treated equally in that agreement. However, the Coalition government did not honour this understanding. (Refer to An Injustice to the remaining 16 Australian citizens).

The Coalition government followed with a similar campaign, reminiscent of the slanderous tactics they employed during the Communist China episode in 1967. They labelled the claims of the sixteen COT cases as frivolous and referred to the individuals involved as vexatious litigants.

But let's take a moment to consider the gravity of the situation: how does the author of this narrative, Alan Smith (me) delve into a far more complex and alarming story that involves government officials who, much like those in the COT (Communications and Technology) story, were willing to jeopardize the lives of their fellow Australians? They concealed even more pressing public interest issues that unfolded over thirty years prior to the events surrounding Telstra and COT. Indeed, some aspects of my story trace back to significant dates between June 28, 1967, and September 18, 1967, when the People's Republic of China arrested me on dubious charges of espionage. My alleged crime stemmed from being seen with a notebook and a pen, where I took meticulous notes about times and dates.

My presence in China was more accidental than intentional; I served as a crew member on a British tramp ship, the Hopepeak.  Our vessel was engaged in the humanitarian task of unloading Australian wheat, which we had loaded at the port of Albany in Western Australia. This shipment was not just ordinary trade; it was sent with the noble intention of alleviating hunger in the suffering nation of China. However, a significant and troubling twist emerged: some of this wheat was redirected to North Vietnam, providing sustenance to the very Viet Cong forces who were at war with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (refer to Chapter 7-Vietnam Viet Cong).

Our vessel was engaged in the humanitarian task of unloading Australian wheat, which we had loaded at the port of Albany in Western Australia. This shipment was not just ordinary trade; it was sent with the noble intention of alleviating hunger in the suffering nation of China. However, a significant and troubling twist emerged: some of this wheat was redirected to North Vietnam, providing sustenance to the very Viet Cong forces who were at war with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (refer to Chapter 7-Vietnam Viet Cong).

As a result, we may be left in the dark about the sheer volume of Australian wheat that found its way into the hands of the Viet Cong guerrilla forces, who marched through the jungles of North Vietnam intending to slaughter and maim as many Australian, New Zealand, and USA troops as possible.

The following three statements taken from a report prepared by Australia's Kim Beasly MP on 4 September 1965 (father of Australia's former Minister of Defence Kim Beasly) only tell part of this tragic episode concerning what I wanted to convey to Malcolm Fraser, former Prime Minister of Australia when I telephoned him in April 1993 and again in April 1994 concerning Australia's wheat deals which I originally wrote to him about on 18 September 1967 as Minister for the Army.

Vol. 87 No. 4462 (4 Sep 1965) - National Library of Australia https://nla.gov.au › nla.obj-702601569

"The Department of External Affairs has recently published an "Information Handbook entitled "Studies on Vietnam". It established the fact that the Vietcong are equipped with Chinese arms and ammunition"

If it is right to ask Australian youth to risk everything in Vietnam it is wrong to supply their enemies. The Communists in Asia will kill anyone who stands in their path, but at least they have a path."

Australian trade commssioners do not so readily see that our Chinese trade in war materials finances our own distruction. NDr do they see so clearly that the wheat trade does the same thing."

Fast forward more than sixty years, and the same bureaucratic patterns persist. Although the individuals in government may have changed, the same public servants continue to shield the misconduct of governmental entities, such as the Wheat Board, which ignored the ethical implications of trading practices. This ongoing trading continued even after I took proactive steps, writing directly to government officials to report my concerns about the misallocation of this vital humanitarian aid.

In early September 1967, members of the Hopeprak crew, myself included, took significant and urgent action after we observed the disturbing re-shipping of Australian wheat destined for North Vietnam. Recognizing the potential implications of this situation, we promptly notified the Seaman’s Union in Australia and the Labor government at the time. Our direct accounts of the events drew considerable attention from the Australian Senate, as documented in the Senate Hansard on September 6, 1967 - https://shorturl.at/ovEW5 shows.

This statement is significant to feature on the absentjustice.com website because it underscores Mr Aldermann, Primary Industry Minister (refer to Senate Hansrd's https://shorturl.at/ovEW5 assertion that the Australian Government appeared unconcerned about the ultimate destination of Australia’s wheat. Alarmingly, it was likely being sent to the North Vietnamese Vietcong, who were in direct conflict with Australian, New Zealand, and American forces during the Vietnam War.

It is crucial to express my concerns regarding the character and priorities of numerous politicians within Australia’s Liberal Coalition. These individuals seem prepared to offload Australian wheat at any price, regardless of the potential consequences. This approach raises serious ethical questions, especially considering that such pricing decisions could ultimately contribute to the safety and well-being of Australian, New Zealand, and American service personnel. The willingness to prioritize profit over the welfare of those who serve abroad in war-torn countries underscores a troubling lack of accountability and responsibility in leadership.

These are the same types of politicians who have consistently overlooked or dismissed the truth surrounding the COT (Casualties of Telstra) issue, raising serious questions about their integrity and commitment to accountability.

Senate Hansard https://shorturl.at/ovEW5 shows Dr Patterson (minister in opposition) asking Mr Aldermann, Primary Industry Minister.

"What guarantees has the Australian Government that Australian wheat being sent to mainland China is not forwarding China to North Vietnam

Mr Adermann, on behalf of the Liberal and Country Party government that had authorised this three-year wheat deal to China - answered Dr Patterson as follows:

"The Australian Government does not exercise control over the ultimate destination of goods purchased by foreign buyers"

I can only assume that Mr Alderman did not have a sibling fighting in North Vietnam when he made that statement on behalf of the Australian government.

Arbitration Flashbacks

My arbitration with Telstra was particularly challenging, as it reignited painful memories I had buried over the years. The Freedom of Information documents I received from Telstra at the start of this process served as a trigger, bringing back flashbacks of my experiences, including being held under armed guard. This traumatic experience profoundly impacted my well-being and state of mind during the arbitration proceedings → British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smiths Seaman.

Among the documents I retrieved from Telstra, I found one particularly alarming file I later shared with the Australian Federal Police. This document contained a record of my phone conversation with Malcolm Fraser, the former Prime Minister of Australia. To my dismay, this Telstra file had undergone redaction. Despite the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s insistence that I should have received this critical information under the Freedom of Information Act, the document and hundreds of requested FOI documents remain withheld from me in 2024.

What information was removed from the Malcolm Fraser FOI released document

The AFP believed Telstra was deleting evidence at my expense

During my first meetings with the AFP, I provided Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose with two Australian newspaper articles concerning two separate telephone conversations with The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, former prime minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.

“Mr Fraser’s request follows the release of a damning government report this week which criticised Telecom for recording conversations without customer permission.

“Mr Fraser said Mr Alan Smith, of the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, phoned him early last year seeking advice on a long-running dispute with Telecom which Mr Fraser could not help.”

During the second interview conducted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) at my business on 26 September 1994, I provided comprehensive responses to 93 questions about unauthorized surveillance and the threats I encountered from Telstra. The Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 includes detailed transcripts of this interview, which extensively address the threats issued by Telstra's arbitration liaison officer, Paul Rumble, and the unlawful interception of my telecommunications and arbitration-related faxes.

It is noteworthy that Paul Rumble and the arbitrator operated in collaboration. Dr. Gordon Hughes supplied Mr. Rumble with my arbitration submission materials months before Telstra should have received these documents, according to the terms of my arbitration agreement.

This situation illustrates a disregard for protocol on the part of Telstra and the individuals overseeing the various COT arbitrations. The processes involved were conducted in a manner likened to a Kangaroo Court.

As a result, we may be left in the dark about the sheer volume of Australian wheat that found its way into the hands of the Viet Cong guerrilla forces, who marched through the jungles of North Vietnam to slaughter and maim as many Australian, New Zealand, and USA troops as possible. The remaining details of my Telstra story, which intertwine with these grave concerns, can be explored more deeply by clicking Chapter 7-Vietnam Vietcong.

Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page

Corrupt practices persisted throughout the COT arbitrations, flourishing in secrecy and obscurity. These insidious actions have managed to evade necessary scrutiny. Notably, the phone issues persisted for years following the conclusion of my arbitration, established to rectify these faults.

Confronting Despair

The independent arbitration consultants demonstrated a concerning lack of impartiality. Instead of providing clear and objective insights, their guidance to the arbitrator was often marked by evasive language, misleading statements, and, at times, outright falsehoods.

Flash Backs – China-Vietnam

In 1967, Australia participated in the Vietnam War. I was on a ship transporting wheat to China, where I learned China was redeploying some of it to North Vietnam. Chapter 7, "Vietnam—Vietcong," discusses the link between China and my phone issues.

A Twenty-Year Marriage Lost

As bookings declined, my marriage came to an end. My ex-wife, seeking her fair share of our venture, left me with no choice but to take responsibility for leaving the Navy without adequately assessing the reliability of the phone service in my pursuit of starting a business.

Salvaging What I Could

Mobile coverage was nonexistent, and business transactions were not conducted online. Cape Bridgewater had only eight lines to service 66 families—132 adults. If four lines were used simultaneously, the remaining 128 adults would have only four lines to serve their needs.

Lies Deceit And Treachery

I was unaware of Telstra's unethical and corrupt business practices. It has now become clear that various unethical organisational activities were conducted secretly. Middle management was embezzling millions of dollars from Telstra.

An Unlocked Briefcase

On June 3, 1993, Telstra representatives visited my business and, in an oversight, left behind an unlocked briefcase. Upon opening it, I discovered evidence of corrupt practices concealed from the government, playing a significant role in the decline of Telstra's telecommunications network.

A Government-backed Arbitration

An arbitration process was established to hide the underlying issues rather than to resolve them. The arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration consultants conducted the process using a modified confidentiality agreement. In the end, the process resembled a kangaroo court.

Not Fit For Purpose

AUSTEL investigated the contents of the Telstra briefcases. Initially, there was disbelief regarding the findings, but this eventually led to a broader discussion that changed the telecommunications landscape. I received no acknowledgement from AUSTEL for not making my findings public.

&am

A Non-Graded Arbitrator

Who granted the financial and technical advisors linked to the arbitrator immunity from all liability regarding their roles in the arbitration process? This decision effectively shields the arbitration advisors from any potential lawsuits by the COT claimants concerning misconduct or negligence.<

The AFP Failed Their Objective

In September 1994, two officers from the AFP met with me to address Telstra's unauthorized interception of my telecommunications services. They revealed that government documents confirmed I had been subjected to these violations. Despite this evidence, the AFP did not make a finding.&am

The Promised Documents Never Arrived

In a February 1994 transcript of a pre-arbitration meeting, the arbitrator involved in my arbitration stated that he "would not determination on incomplete information.". The arbitrator did make a finding on incomplete information.